Describing his rented house, Kinbote (in VN’s novel Pale Fire, 1962, Shade’s mad commentator who imagines that he is Charles the Beloved, the last self-exiled king of Zembla) mentions his landlord’s four daughters (Alphina, Betty, Candida and Dee):

In the Foreword to this work I have had occasion to say something about the amenities of my habitation. The charming, charmingly vague lady (see note to line 691), who secured it for me, sight unseen, meant well, no doubt, especially since it was widely admired in the neighborhood for its "old-world spaciousness and graciousness." Actually, it was an old, dismal, white-and-black, half-timbered house, of the type termed wodnaggen in my country, with carved gables, drafty bow windows and a so-called "semi-noble" porch, surmounted by a hideous veranda. Judge Goldsworth had a wife, and four daughters. Family photographs met me in the hallway and pursued me from room to room, and although I am sure that Alphina (9), Betty (10), Candida (12), and Dee (14) will soon change from horribly cute little schoolgirls to smart young ladies and superior mothers, I must confess that their pert pictures irritated me to such an extent that finally I gathered them one by one and dumped them all in a closet under the gallows row of their cellophane-shrouded winter clothes. In the study I found a large picture of their parents, with sexes reversed, Mrs. G. resembling Malenkov, and Mr. G. a Medusa-locked hag, and this I replaced by the reproduction of a beloved early Picasso: earth boy leading raincloud horse. I did not bother, though, to do much about the family books which were also all over the house - four sets of different Children's Encyclopedias, and a stolid grown-up one that ascended all the way from shelf to shelf along a flight of stairs to burst an appendix in the attic. Judging by the novels in Mrs. Goldsworth's boudoir, her intellectual interests were fully developed, going as they did from Amber to Zen. The head of this alphabetic family had a library too, but this consisted mainly of legal works and a lot of conspicuously lettered ledgers. All the layman could glean for instruction and entertainment was a morocco-bound album in which the judge had lovingly pasted the life histories and pictures of people he had sent to prison or condemned to death: unforgettable faces of imbecile hoodlums, last smokes and last grins, a strangler's quite ordinary-looking hands, a self-made widow, the close-set merciless eyes of a homicidal maniac (somewhat resembling, I admit, the late Jacques d'Argus), a bright little parricide aged seven ("Now, sonny, we want you to tell us -"), and a sad pudgy old pederast who had blown up his blackmailer. What rather surprised me was that he, my learned landlord, and not his "missus," directed the household. Not only had he left me a detailed inventory of all such articles as cluster around a new tenant like a mob of menacing natives, but he had taken stupendous pains to write out on slips of paper recommendations, explanations, injunctions and supplementary lists. Whatever I touched on the first day of my stay yielded a specimen of Goldsworthiana. I unlocked the medicine chest in the second bathroom, and out fluttered a message advising me that the slit for discarded safety blades was too full to use. I opened the icebox, and it warned me with a bark that "no national specialties with odors hard to get rid of" should be placed therein. I pulled out the middle drawer of the desk in the study - and discovered a catalogue raisonné of its meager contents which included an assortment of ashtrays, a damask paperknife (described as "one ancient dagger brought by Mrs. Goldsworth's father from the Orient"), and an old but unused pocket diary optimistically maturing there until its calendric correspondencies came around again. Among various detailed notices affixed to a special board in the pantry, such as plumbing instructions, dissertations on electricity, discourses on cactuses and so forth, I found the diet of the black cat that came with the house:

Mon, Wed, Fri: Liver

Tue, Thu, Sat: Fish

Sun: Ground meat

(All it got from me was milk and sardines; it was a likable little creature but after a while its movements began to grate on my nerves and I farmed it out to Mrs. Finley, the cleaning woman.) But perhaps the funniest note concerned the manipulations of the window curtains which had to be drawn in different ways at different hours to prevent the sun from getting at the upholstery. A description of the position of the sun, daily and seasonal, was given for the several windows, and if I had heeded all this I would have been kept as busy as a participant in a regatta. A footnote, however, generously suggested that instead of manning the curtains, I might prefer to shift and reshift out of sun range the more precious pieces of furniture (two embroidered armchairs and a heavy "royal console") but should do it carefully lest I scratch the wall moldings. I cannot, alas, reproduce the meticulous schedule of these transposals but seem to recall that I was supposed to castle the long way before going to bed and the short way first thing in the morning. My dear Shade roared with laughter when I led him on a tour of inspection and had him find some of those bunny eggs for himself. Thank God, his robust hilarity dissipated the atmosphere of damnum infectum in which I was supposed to dwell. On his part, he regaled me with a number of anecdotes concerning the judge's dry wit and courtroom mannerisms; most of these anecdotes were doubtless folklore exaggerations, a few were evident inventions, and all were harmless. He did not bring up, my sweet old friend never did, ridiculous stories about the terrifying shadows that Judge Goldsworth's gown threw across the underworld, or about this or that beast lying in prison and positively dying of raghdirst (thirst for revenge) - crass banalities circulated by the scurrilous and the heartless - by all those for whom romance, remoteness, sealskin-lined scarlet skies, the darkening dunes of a fabulous kingdom, simply do not exist. But enough of this. Let us turn to our poet's windows. I have no desire to twist and batter an unambiguous apparatus criticus into the monstrous semblance of a novel. (note to Lines 47-48)

Christopher Smart's poem Jubilate Agno (written between 1759 and 1763, during Smart's confinement for insanity in St. Luke's Hospital, Bethnal Green, London, and first published in 1939 under the title Rejoice in the Lamb: A Song from Bedlam) is divided into four fragments labeled "A," "B," "C," and "D." The whole work consists of over 1,200 lines: all the lines in some sections begin with the word Let; those in other sections begin with For. Those in the series beginning with the word "Let," associated names of human beings, mainly biblical, with various natural objects; and those beginning with the word "For" are a series of aphoristic verses. In Fragment B [2] of Jubilate Agno Smart mentions Dee:

Let Luke rejoice with the Trout -- Blessed be Jesus in Aa, in Dee and in Isis.

Agno is dative/ablative singular of agnus (Lat., lamb). In a letter of Nov. 16, 1823, from Odessa to Delvig in St. Petersburg Pushkin says that, as soon as he gets Delvig's, Yazykov's and Baratynski's verses, he will slay the lamb (zakolyu agntsa):

На днях попались мне твои прелестные сонеты — прочёл их с жадностью, восхищением и благодарностию за вдохновенное воспоминание дружбы нашей. Разделяю твои надежды на Языкова и давнюю любовь к непорочной музе Баратынского. Жду и не дождусь появления в свет ваших стихов; только их получу, заколю агнца, восхвалю господа — и украшу цветами свой шалаш — хоть Бируков находит это слишком сладострастным. Сатира к Гнедичу мне не нравится, даром что стихи прекрасные; в них мало перца; Сомов безмундирный непростительно. Просвещённому ли человеку, русскому ли сатирику пристало смеяться над независимостию писателя?

Pushkin praises Delvig's sonnets, but says that he dislikes Baratynski's Satire to Gnedich, because there is too little pepper in it. Nikolay Gnedich (1784-1833) is the author of the Russian translation of The Iliad (1807-29). In 1830 Pushkin wrote the following epigram:

Крив был Гнедич поэт, преложитель слепого Гомера,

Боком одним с образцом схож и его перевод.

Poet Gnedich, renderer of Homer the Blind, was himself one-eyed,

Likewise, his translation is only half like the original.

Christopher Smart is the author of The Hilliad, a mock epic poem written as a literary attack upon John Hill on 1 February 1753. The title is a play on Alexander Pope's The Dunciad with a substitution of Hill's name, which represents Smart's debt to Pope for the form and style of The Hilliad as well as a punning reference to the Iliad. The poet in Pale Fire, John Shade is an authority on Pope (who mentions Zembla in his Essay on Man, 1733-34).

In the same letter of Nov. 16, 1823, to Delvig Pushkin says that he is writing a new poem (as Pushkin calls Eugene Onegin):

Пишу теперь новую поэму, в которой забалтываюсь донельзя.

Baron Anton Delvig (1798-1831) was Pushkin's Lyceum friend. In Chapter Eight (I: 3-4) of EO Pushkin says that at the Lyceum he would eagerly read Apuleius and did not read Cicero:

В те дни, когда в садах Лицея

Я безмятежно расцветал,

Читал охотно Апулея,

А Цицерона не читал,

В те дни, в таинственных долинах,

Весной, при кликах лебединых,

Близ вод, сиявших в тишине,

Являться Муза стала мне.

Моя студенческая келья

Вдруг озарилась: Муза в ней

Открыла пир младых затей,

Воспела детские веселья,

И славу нашей старины,

И сердца трепетные сны.

И свет ее с улыбкой встретил;

Успех нас первый окрылил;

Старик Державин нас заметил

И, в гроб сходя, благословил.

In those days when in the Lyceum's gardens

I bloomed serenely,

would eagerly read Apuleius,

did not read Cicero;

in those days, in mysterious valleys,

in springtime, to the calls of swans,

near waters shining in the stillness,

the Muse began to visit me.

My student cell was all at once

radiant with light: in it the Muse

opened a banquet of young fancies,

sang childish gaieties,

and glory of our ancientry,

and the heart's tremulous dreams.

And with a smile the world received her;

the first success provided us with wings;

the aged Derzhavin noticed us — and blessed us

as he descended to the grave.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, writer and Academic skeptic, 103 BC - 43 BC) is the author of Oratio in Toga Candida, a speech given by Cicero during his election campaign for the consulship of 63 BC. Oratio + hombre = Horatio + ombre. Hombre is Spanish for "man," ombre is French for "shade." According to Kinbote, after line 274 of Shade’s poem there is a false start in the draft:

I like my name: Shade, Ombre, almost 'man'

In Spanish... (note to Line 275)

Horatio is a character in Shakespeare's Hamlet (Hamlet's best friend and fellow student at Wittenberg). In Eugène Delacroix's painting Hamlet with Horatio, the Gravedigger Scene (1838) Horatio is dressed in red:

According to Kinbote, the king escaped from Zembla dressed as an athlete in scarlet wool:

A professor of physics now joined in. He was a so-called Pink, who believed in what so-called Pinks believe in (Progressive Education, the Integrity of anyone spying for Russia, Fall-outs occasioned solely by US-made bombs, the existence in the near past of a McCarthy Era, Soviet achievements including Dr. Zhivago, and so forth): "Your regrets are groundless" [said he]. "That sorry ruler is known to have escaped disguised as a nun; but whatever happens, or has happened to him, cannot interest the Zemblan people. History has denounced him, and that is his epitaph."

Shade: "True, sir. In due time history will have denounced everybody. The King may be dead, or he may be as much alive as you and Kinbote, but let us respect facts. I have it from him [pointing to me] that the widely circulated stuff about the nun is a vulgar pro-Extremist fabrication. The Extremists and their friends invented a lot of nonsense to conceal their discomfiture; but the truth is that the King walked out of the palace, and crossed the mountains, and left the country, not in the black garb of a pale spinster but dressed as an athlete in scarlet wool."

"Strange, strange," said the German visitor, who by some quirk of alderwood ancestry had been alone to catch the eerie note that had throbbed by and was gone. (note to Line 894)

Describing this conversation at the Faculty Club, Kinbote compares Gerald Emerald (a young instructor at Wordsmith University who gives Gradus a lift to Kinbote's rented house in New Wye) to a disciple in Leonardo's Last Supper:

In the meantime, at the other end of the room, young Emerald had been communing with the bookshelves. At this point he returned with the T-Z volume of an illustrated encyclopedia.

"Well, said he, "here he is, that king. But look, he is young and handsome" ("Oh, that won't do," wailed the German visitor). "Young, handsome, and wearing a fancy uniform," continued Emerald. "Quite the fancy pansy, in fact."

"And you," I said quietly, "are a foul-minded pup in a cheap green jacket."

"But what have I said?" the young instructor inquired of the company, spreading out his palms like a disciple in Leonardo's Last Supper.

"Now, now," said Shade. "I'm sure, Charles, our young friend never intended to insult your sovereign and namesake."

"He could not, even if he had wished," I observed placidly, turning it all into a joke.

Gerald Emerald extended his hand - which at the moment of writing still remains in that position. (ibid.)

The central figure in Leonardo's Last Supper is Jesus Christ (who was called Agnus Dei, "the Lamb of God," by St. John the Baptist). In Pushkin's Stsena iz Fausta ("A Scene from Faust," 1825) Mephistopheles reads Faust's thoughts and calls Gretchen agnets moy poslushnyi ("my dutiful lamb"):

Мефистофель

Ты думал: агнец мой послушный!

Как жадно я тебя желал!

Как хитро в деве простодушной

Я грезы сердца возмущал! —

Любви невольной, бескорыстной

Невинно предалась она…

Что ж грудь моя теперь полна

Тоской и скукой ненавистной?..

На жертву прихоти моей

Гляжу, упившись наслажденьем,

С неодолимым отвращеньем:

Так безрасчетный дуралей,

Вотще решась на злое дело,

Зарезав нищего в лесу,

Бранит ободранное тело; —

Так на продажную красу,

Насытясь ею торопливо,

Разврат косится боязливо…

Потом из этого всего

Одно ты вывел заключенье…

Фауст

Сокройся, адское творенье!

Беги от взора моего!

MEPHISTOPHELES

You thought: sweet angel of devotion!

I longed for you so avidly!

How cunningly I set in motion

A pure heart’s girlish fantasy!

Her love’s spontaneous, self-forgetful;

She gives herself in innocence …

Why does my heart, in recompense

Feel its old tedium grow more hateful?

I look upon her now, poor thing,

A victim of my whim’s compulsion,

With insurmountable revulsion.

So does a fool, unreckoning,

But bent on doing something evil,

For a trifle slit some beggar’s throat,

Then curses the poor ragged devil.

So on the beauty he has bought

The rake, enjoying her in haste,

Now looks timidly shame-faced.

So, adding it all up, you might

See one conclusion to be drawn …

FAUST

You hellish creature, away, begone!

Don’t let me catch you in my sight!

(tr. Alan Shaw)

Odno ty vyvel zaklyuchen'ye (One conclusion you have drawn), a line in Pushkin's "Scene from Faust," brings to mind Odon (the stage name of Donald O'Donnell, a world famous actor and Zemblan patriot who helps the king to escape from Zembla) and his half-brother Nodo (a cardsharp and despicable traitor).

In Part Two of Goethe's tragedy Faust marries Helen of Troy (a character in The Iliad). The opening lines of Goethe's Erlkönig (1782), Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind? / Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind (Who rides so late through night and wind? / It is the father with his child) are a leitmotif in Canto Three of Shade's poem:

"What is that funny creaking - do you hear?"

"It is the shutter on the stairs, my dear."

"If you're not sleeping, let's turn on the light.

I hate that wind! Let's play some chess." "All right."

"I'm sure it's not the shutter. There - again."

"It is a tendril fingering the pane."

"What glided down the roof and made that thud?"

"It is old winter tumbling in the mud."

"And now what shall I do? My knight is pinned."

Who rides so late in the night and the wind?

It is the writer's grief. It is the wild

March wind. It is the father with his child. (ll. 653-664)

In Goethe's Faust the cosmic chess game takes place between Faust and Mephistopheles. Die Schachspieler ("The Chess Players," 1822) is a painting by Moritz Retzsch depicting Faust and Mephistopheles at a chessboard:

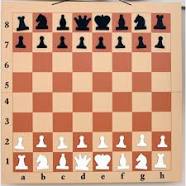

The eight vertical lines or columns of a chessboard, files, are labeled a b c d e f g h:

A German painter, Moritz Retzsch (1779-1857) was also a winemaker, a member of the Saxon wine association from 1799 onwards. According to Kinbote, almost the whole clan of Gradus (Shade's murderer) was in the liquor business:

By an extraordinary coincidence (inherent perhaps in the contrapuntal nature of Shade's art) our poet seems to name here (gradual, gray) a man, whom he was to see for one fatal moment three weeks later, but of whose existence at the time (July 2) he could not have known. Jakob Gradus called himself variously Jack Degree or Jacques de Grey, or James de Gray, and also appears in police records as Ravus, Ravenstone, and d'Argus. Having a morbid affection for the ruddy Russia of the Soviet era, he contended that the real origin of his name should be sought in the Russian word for grape, vinograd, to which a Latin suffix had adhered, making it Vinogradus. His father, Martin Gradus, had been a Protestant minister in Riga, but except for him and a maternal uncle (Roman Tselovalnikov, police officer and part-time member of the Social-Revolutionary party), the whole clan seems to have been in the liquor business. Martin Gradus died in 1920, and his widow moved to Strasbourg where she soon died, too. Another Gradus, an Alsatian merchant, who oddly enough was totally unrelated to our killer but had been a close business friend of his kinsmen for years, adopted the boy and raised him with his own children. It would seem that at one time young Gradus studied pharmacology in Zurich, and at another, traveled to misty vineyards as an itinerant wine taster. We find him next engaging in petty subversive activities - printing peevish pamphlets, acting as messenger for obscure syndicalist groups, organizing strikes at glass factories, and that sort of thing. Sometime in the forties he came to Zembla as a brandy salesman. There he married a publican's daughter. His connection with the Extremist party dates from its first ugly writhings, and when the revolution broke out, his modest organizational gifts found some appreciation in various offices. His departure for Western Europe, with a sordid purpose in his heart and a loaded gun in his pocket, took place on the very day that an innocent poet in an innocent land was beginning Canto Two of Pale Fire. We shall accompany Gradus in constant thought, as he makes his way from distant dim Zembla to green Appalachia, through the entire length of the poem, following the road of its rhythm, riding past in a rhyme, skidding around the corner of a run-on, breathing with the caesura, swinging down to the foot of the page from line to line as from branch to branch, hiding between two words (see note to line 596), reappearing on the horizon of a new canto, steadily marching nearer in iambic motion, crossing streets, moving up with his valise on the escalator of the pentameter, stepping off, boarding a new train of thought, entering the hall of a hotel, putting out the bedlight, while Shade blots out a word, and falling asleep as the poet lays down his pen for the night. (note to Line 17)

In Goethe's tragedy Mephistopheles calls Faust ein Mann von vielen Graden (a man of manifold degrees):

Mephistopheles:

Genug, genug, o treffliche Sibylle!

Gib deinen Trank herbei, und fülle

Die Schale rasch bis an den Rand hinan;

Denn meinem Freund wird dieser Trunk nicht schaden:

Er ist ein Mann von vielen Graden,

Der manchen guten Schluck getan.

Mephistopheles:

O Sibyl excellent, enough of adjuration!

But hither bring us thy potation,

And quickly fill the beaker to the brim!

This drink will bring my friend no injuries:

He is a man of manifold degrees,

And many draughts are known to him. (Part One, “Witches’ Kitchen”)

Treffliche Sibylle (excelent Sibyl), as Mephistopheles calls the witch who offers Faust the potion, brings to mind Sybil Shade (the poet's wife). In Christopher Smart's The Hilliad Sybil seduces Hillario to give up his career as an apothecary and become a writer instead. The title of Smart's poem makes one think of chiliasm, the doctrine of Christ's expected return to reign on earth for 1000 years. Pale Fire is a poem in heroic couplets, of nine hundred ninety-nine lines, divided into four cantos. Shade’s poem is almost finished when the author is killed by Gradus. Kinbote believes that, to be completed, Shade’s poem needs but one line (Line 1000, identical to Line 1: “I was the shadow of the waxwing slain”). But it seems that, like some sonnets, Shade's poem also needs a coda (Line 1001: “By its own double in the windowpane”). Dvoynik ("The Double") is a short novel (1846) by Dostoevski and a poem (1909) by Alexander Blok. The name of Blok's family estate in the Province of Moscow, Shakhmatovo comes from shakhmaty (chess).