Download PDF of Number 74 (Spring/Fall 2015) The Nabokovian.

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 74 Spring/Fall 2015

___________________________________________________CONTENTS

From the Editor; News 4

by Stephen Blackwell

Notes And Brief Commentaries 6

Edited by Priscilla Meyer

Another Adelaida: Dostoevsky’s The Idiot

in Nabokov’s Ada 6

Victor Fet and Slav N. Gratchev

Crocus; The Poet’s Mushroom; On Shamoes 11

Steven Mihalik

Source of a Symbol? 14

John Hoffnagle

Scent of a Woman: Olfaction Metaphors 15

in Vladimir Nabokov’s Novels

Ljuba Tarvi

Despair Disassociated 19

Luke Maxted

Annotations to Ada, 40: Part 1 Chapter 40 26

by Brian Boyd

[3]

From the Editor

by Stephen Blackwell

This issue marks the final edition of The Nabokovian to appear primarily in print, in accordance with the vote of the membership upon the recent proposals on the Society’s future. In short order, the web site should become very active, and as things currently stand, a printed version of certain items from the site will be produced twice a year (subject to space limitations), and sold at cost to those wishing to pay for it.

As many society members know, The Nabokovian was created in 1978 by Stephen Jan Parker as the Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter. It transformed into its current format in 1985. The “Notes and Brief Annotations” section began its life as “Annotations and Queries” and has been edited over the years by Charles Nicol, Gennady Barabtarlo, and of course its current master of ceremonies, Priscilla Meyer. The checklist of criticsm (later, “Bibliography”) was added in the third number, and for many years was produced by Steve Parker, alone or in collaboration with his graduate students. He was succeeded in this endeavor by his former student Sidney Dement. Brian Boyd’s popular “Annotations to Ada” began to appear in Spring 1993, and have been a mainstay of the journal ever since. Throughout Steve Parker’s years as Editor and Publisher of the journal, he was assisted by Ms. Paula Courtney, and the two of them produced 71 issues with admirable regularity.

In recent years, many of the original functions of The Nabokovian were taken over or supplemented by Nabokv-L, founded by D. Barton Johnson for the Society, or by other web-based resources such as ZEMBLA, created by Jeff Edmunds on the Penn State University’s library servers. Throughout all that time, The Nabokovian continued to be relevant to the Society’s members, serving as an ideal place to publish brief “note”-style discoveries that could not be submitted to regular scholarly journals. As a result of this openness, many Nabokov scholars (professional and otherwise) saw their first publications appear on these pages.

It seems only fitting that the name The Nabokovian will now adorn the Society’s web space, which will be home to the sections previously housed in the printed journal, and also new departments that may be launched by intrepid colleagues. Brian Boyd will continue to publish his “Annotations” here first, six months before

[4]

making them accessible at his AdaOnline site. The new site will be more flexible than the print publication; it will certainly grow to contain many new features, and who knows what interesting forms and variations it will evolve into during the coming years. All Society members are encouraged to contribute to the life of the new Nabokovian web site.

Society News

Not only was the first round of bylaws changes approved by the membership in January 2016, but Thomas Karshan was elected the new Vice President, with Zoran Kuzomanovich moving up to the presidency and Leland de la Durantaye assuming his post on the Board.

Jeff Edmunds announced in November, 2015, on ZEMBLA’s 20th anniversary, that his Kinbotean web site would become a static archive, no longer accepting any submissions or corrections of any material. Jeff’s generous and inspiring contributions to the world of Nabokov enthusiasts will (let’s hope) remain as a monument in perpetuity, its contents permanently available to all seeking them out to stimulate and advance their own research or their understanding of Nabokov’s art. Special thanks and tribute are due to Jeff and to everyone who helped him make ZEMBLA a key fixture of Nabokov life for the past two decades.

Susan Elizabeth Sweeney and I recently announced the end of our tenure at the helm of Nabokv-L, and the accession of Dana Dragunoiu and Stanislav Shvabrin as the new co-editors. We are grateful to them, and confident and excited about the future of the List in their able hands.

Future print editions of The Nabokovian will require a new Editor to oversee the process of selecting contents from the web site, light editing, formatting, printing, and mailing to the subset of members who choose to purchase this optional edition. Ideally, said Editor will come from the ranks of those wishing to see a print edition continue (about 30-35% of the membership, last year). I will be most willing to help the next Editor with all technical details of such a venture for as long as necessary. The new Editor will be

[5]

selected by the Society’s Board of Directors, but those interested are invited to write to me (sblackwe@utk.edu) putting their names forward.

Nabokov Studies biennial prize winners were announced:

The Donald Barton Johnson Prize for the best essay pub-lished in Nabokov Studies: Deborah Anne Martinsen, for “Lolita as a St. Petersburg Text.” The Samuel Schuman Prize for the best first book on Nabokov: Julia Trubikhina, for The Trans-lator’s Doubts: Vladimir Nabokov and the Ambiguity of Translation. The Kuzmanovich Family Prize for the best dissertation on Nabokov: Constantine Muravnik for Nabokov’s Philosophy of Art.

Beginning this year, Nabokov Studies, now electronic, will be an official benefit of Society membership. Those who have access through their institutional affiliations will continue to make use of those channels. Members lacking such access can receive a rights-managed PDF of the journal by writing to its editor, Zoran Kuzmanovich, at zokuzmanovich@davidson.edu.

Zoran is also organizing a conference for September 2016, to take place in either Key West, Florida, or Honolulu, Hawaii. Look for announcements and details on Nabokv-L, on the web site (www.nabokovsociety.org), and in your email.

As of this writing, the Society has eighty-five individual members, a slight decline from last year. As the new Web Site expands its content and reputation, the Board expects to see significant growth in membership.

As my last word on this last print-only Nabokovian, I’d like to express my thanks to all contributors to the journal during my time here, as well as to everyone who has uttered or sent me kind and supportive words for my small efforts on behalf of the Society. It has been a real pleasure being a part of the team that keeps the IVNS ticking, and it will be an even greater pleasure to watch the next generation of Nabokovians propel our industrious guild to new heights.

[6]

Notes And Brief Commentaries

Edited by Priscilla Meyer

Another Adelaida: Dostoevsky’s The Idiot in Nabokov’s Ada

Ada (full name Adelaida) Veen is the main female character in Nabokov’s Ada (1969). Multiple origins of the name, uncommon in Russia, are possible. Russian “ad” (hell) is an obvious component. Hence the well-studied duality of Ardis, and the entire planet of Antiterra (Demonia), as both heaven and hell. “Adah, in the verse tragedy Cain: A Mystery (1821), by Lord Byron, is both wife and twin sister of Cain” (Boyd, B. AdaOnline, http://www.ada.auckland.ac.nz/).

Ada Veen’s proficiency in science brings to mind a relevant, real female scholar, Ada Lovelace (1815-1852), the daughter of the same Lord Byron. This Ada famously worked with Charles Babbage on developing his Analytical Machine, a prototype of modern computers (never built), and is considered the first computer programmer. Babbage called her “The Enchantress of Numbers.” Ada Lovelace, also interested in phrenology and mesmerism, described her approach as “poetical science.” Her father, Lord Byron, of course, is the most important literary influence in Russian literature in relation to Pushkin; Nabokov himself discussed Byron many times, particularly in his Eugene Onegin commentary.

The name Ada, amazingly, appears in one of the earliest of Nabokov’s works: his translation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (Anya v strane chudes, Berlin: Gamaiun, 1923). The young translator deployed the “Anya–Ada–Asya” word sequence (Doublets game, or world golf, invented by Lewis Carroll himself) to emphasize his Anya’s transformations (for more detail, see: Fet, V. “Beheading First: On Nabokov’s Translation of Lewis Carroll. The Nabokovian, 2009, 63, 52–63).

It appears, however, that Ada scholars have overlooked the only Adelaida existing in major Russian literature. It is Adelaida Yepanchina, the middle daughter of General Yepanchin in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (1868). All three daughters have names starting with “A”: Alexandra, Adelaida, Aglaya (compare this to Nabokov’s Anya–Ada–Asya).

[7]

Ada famously starts with a mockery of Tolstoy novel’s very first sentence. “In inverting Anna Karenin’s opening sentence, Van tries to claim that, unlike Tolstoy’s novel, Ada is no tragedy but the happy story of a unique family” (Boyd, B. Nabokov’s Ada: The Place of Consciousness. Ann Arbor, MI: Ardis, 1985, 103). It appears that this important beginning might also refer to The Idiot, another opposite of a happy family chronicle. The Yepanchins, to whom we are introduced in the very first paragraphs of The Idiot, are indeed a very unhappy family. The novel’s protagonist Prince Myshkin, a Christ-like figure, is mentally unstable and his attempts at family life are disastrous. Myshkin is given Tolstoy’s first name and patronymic, Lev Nikolaevich—a sign of Dostoevsky’s constant argument with Tolstoy (the two never met).

Like Nabokov’s Ada, Dostoevsky’s Adelaida is an artist. She paints nothing but landscapes and portraits that she never can finish, according to Mrs. Yepanchina, her mother. This is how Dostoevsky has Adelaida introduce herself: “For two years, I cannot find an idea for my new painting. Prince, give me an idea.” So it is to her that Prince Myshkin makes a remarkable suggestion, to paint an “invitation to a beheading”: “…indeed, I had a thought… to paint the face of a sentenced man, one minute before the guillotine would fall, when he is already standing on the scaffold, just before he would lie on that block.”

Adelaida does not speak much but when her opinion is needed she ignores her family’s ironical attitude toward the Prince. She is the only female character in The Idiot who is genuinely interested in Myshkin and in his words. All others take him for a fool, she takes him for a philosopher; all others mock him, she asks him to teach her and give her an idea for a painting. Adelaida is the first, and the only one, to defend Myshkin in front of her mother and Aglaya. One can see an inner connection between her and Myshkin: while everyone is making fun of him, Adelaida says thoughtfully: “You are a philosopher and came to teach us… teach us, please.” This is the most exact characteristic of Myshkin, and the highest praise that he will ever hear. “…You have the face of a kind sister,” says Myshkin to Adelaida, who clearly has a special place in Dostoevsky’s heart—and is rewarded with a happy ending: she happily marries one “Prince Shch.”

Let us now turn to the real-life prototypes of the Yepanchin family in The Idiot. This, unexpectedly, will bring us to the Ada

[8]

Lovelace connection again. Her younger Russian counterpart, indeed another “Enchantress of Numbers,” is the famous, precocious mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaya (1850-1891). In the best tradition of Nabokovian puzzles or chess problems, we discover that Sofia’s older sister Anna was a prototype of Adelaida Yepanchina’s younger sister, Aglaya.

It is commonly believed that the Yepanchins are loosely based on the family of the General Vasily Korvin-Krukovsky. Dostoevsky was a frequent guest of this family after his return from Siberian exile. The general had two daughters, Anna (the older) and Sofia (the younger). Anna’s first attempts at writing prose were encouraged by Dostoyevsky. Both girls were rebellious, knew and read Chernyshevsky, and both later married untraditionally.

In 1865, Dostoevsky (then 44) proposed to 21 year-old Anna Korvin-Krukovskaya (1843-1887), and was rejected. Anna is considered to be a prototype of a beautiful and cruel “nihilist,” the 20 year-old Aglaya Yepanchina in The Idiot. In the novel, Aglaya is the youngest of three sisters who, in the end, marries a Polish count and revolutionary, and converts to Catholicism (a great sin for Dostoevsky, and a reference to the Krukovsky family’s Polish roots). As if following the novelist’s prophecy, the real Anna Korvin-Krukovskaya married in 1870 a French army colonel, and a revolutionary, Victor Jaclard. Together with Sofia and her husband, the Jaclards were active in the Paris Commune in 1871. Later, Anna Jaclard became a well-known writer in Russia. She maintained her friendship with Dostoevsky.

The Idiot’s first chapter appeared in 1868. The same year, 18 year-old Sofia Korvin-Krukovskaya married Vladimir Kovalevsky, in a “fictitious marriage” (exactly as recommended in Chernyshevsky’s What To Be Done, 1862-1863), in order to be able to be educated in Europe. At some point, the marriage was consummated, and in 1878 they had a daughter. Vladimir, who became a famous paleontologist and a personal friend of Charles Darwin, committed suicide in 1883. Sofia Kovalevskaya became the first female Professor of Mathematics in history (Stockholm University, 1884). Her discoveries in mathematics continued the work of Leonhard Euler (see Ada about Van Veen who “could solve an Euler-type problem or learn by heart Pushkin’s Headless Horseman poem in less than twenty minutes”).

[9]

In her 1890 autobiography (Kovalevskaya, S.V. Vospominaniya. Povesti. Nauka: Moscow, 1974), Sofia remembers in great detail Dostoevsky’s courting Anna. Sofia was 15 years old, and fell in love with the famous writer herself. “I was sitting close, without interrupting the conversation, looking at Fyodor Mikhaylovich, and listened with great attention to everything he was saying. He seemed to me now an absolutely different man, very young, sincere, kind, and intelligent. “Is it true that he is 43 years old?” I thought. “Is it possible that he is three times older than me?”

Sofia’s genuine interest in Dostoevsky certainly reminds us of Adelaida’s attention to Myshkin: while her parents are suspicious and skeptical about Dostoevsky (“What do we know about him? Only that he is a journalist and a former inmate. A good recommendation!”), Sofia knows that he is a great writer. “He was like a friend”; the 15-year old girl “immediately felt that Dostoevsky was very kind and close” to her.

We might see Sofia Kovalevskaya reflected also in Princess Sofia Temnosiny, the ancestral female in the Veen line in Ada. (Temnosinys were a real ancient princely family, which expired only in the 19th century). “Princess Sofia” is reminiscent of real Russian female rulers: Princess Sofia Romanova, sister of Peter the Great; or even Princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg, better known as Empress Catherine the Great. However, the name also refers to Sophia as an ancient symbol of Wisdom—Judaic, Gnostic, and Christian, as the martyr mother of Saints Faith, Hope, and Charity (three Christian virtues; 1 Corinthians 13:13). In the Russian tradition, Charity becomes Love, and the triple saints are Vera, Nadezhda, Liubov’. This Sophia was also the most important symbol for Russian Symbolists of the Silver Age (Vladimir Solovyov, Blok, Bely, etc.). The Latin equivalent of Sophia is Sapientia, which directly connects us to the Linnaean name of our species.

The complex, mocking biography of Chernyshevsky in Chapter 4 of Nabokov’s Dar (The Gift, 1938) is “based” on an imaginary work of one Strannolyubsky (“Strangelove”), “his best biographer.” The real Alexander Nikolaevich Strannolyubsky (1839-1903) was a St. Petersburg mathematician who tutored Chernyshevsky’s son, and is in fact playfully mentioned in The Gift as “the critic’s father?” (Strannolyubsky’s name appears in a letter to Chernyshevsky from his wife Olga Sokratovna dated 4 August 1888). Twenty years earlier

[10]

(1866-68), this real Strannolyubsky was also the first tutor of young Sofia Korvin-Krukovskaya, just before she married Vladimir Kovalevsky and moved to Europe (Vorontsova, L.A. Sofya Kovalevskaya, Molodaya Gvardiya: Moscow, 1957). It was Sofia Kovalevskaya who suggested that Sasha Chernyshevsky should study mathematics (A. Sklyarenko, NABOKOV-L, 8 June 2013). Sofia’s tutor in Berlin in 1870-1874 was the famous German mathematician, Karl Weierstrass (1815-1897), who also taught Nikolai Bugaev, father of the poet Andrey Bely.

In Ada, the Korvin-Krukovsky family could also provide one of the sources of “Raven”—the nickname of Ada Veen’s father, Demon Veen. The name “Korvin” (Korwin, Corvin) is common in Poland and Hungary, and derives from Corvinus (Lat., raven). Matthias Corvinus (1458-1490), the Renaissance “raven king” of Hungary, who had the largest library in Europe, was part of Korvin-Krukovsky’s family legend. In fact, “Korvin” was formally added to the Krukovsky surname only in 1858, when the vain General proved his aristocratic family connections (V. P. Rumyantseva, Rodoslovnaya Korvin-Krukovskikh [Genealogy of Korvin-Krukovskys]. Nevelsky sbornik, St. Petersburg, 1997, 2, 146–157.) The Polish version of the name, known from the 13th century, is Slepowron (Blind Raven); their coat-of-arms featured a raven holding a golden ring in its beak. An ardent Ada scholar would be tempted to decode “Corvin” as “Cor Vin” (Lat., “heart of Veen”).

The timeline in Ada’s Part 1 is 1863-1888. Scholars have not really explained why. This blissful time in Amerussia, however, corresponds to some particularly tumultuous years in real Russia: from the hope of the Great Reforms of Alexander II (1861) to his assassination by “the possessed” terrorists of the People’s Will in 1881, two months after Dostoevsky’s death. In the literary context, these decades were the formative time of the greatest Russian prose. We know that Nabokov admired Tolstoy and denied Dostoevsky the rank of a great writer. On Antiterra, Tolstoy is much more visible, and references to Dostoevsky are hidden, but in real history, both were most important figures who exerted immense influence on all future writers on Earth.

—Victor Fet and Slav N. Gratchev, Huntington, WV

[11]

Crocus; The Poet’s Mushroom

In support of the reading of The Real Life of Sebastian Knight that postulates a spectral Sebastian guiding V. from beyond the grave, there is previously unnoticed material in Chapter Five. Some, such as Michael Dirda in his introduction to the New Directions edition of the text (1998), draw attention to the very mysterious (most likely Russian Blue) cat who, while Sebastian is being discussed, strangely “does not seem to know milk all of a sudden” (Nabokov 50), and who casts a shadowy presence throughout the chapter. There are various textual indices of chapter five’s extra-ordinary qualities, not the least of which is the literal evocation of “Sebastian’s spirit,” which “seemed to hover about us with the flicker of the fire reflected in the brass knobs of the hearth” (45-46). But perhaps the most compelling evidence is disguised within the parenthetical detail given by V. that “it was a bleak day in February,” and in Sebastian’s unnamed friend’s insistence that V. “[c]ome along and visit the crocuses, Sebastian used to call them ‘the poet’s mushrooms,’ if you see what he meant” (51).

In 1922, Cambridge University Press (Sebastian’s alma mater) published an anthology of poetry called The Poets’ Year, which uses the days and months of the year as its structural framework. Under February fourth is found the following poem by Coventry Patmore (The Poets’ Year, Reprint. Ed. Ada Sharpley. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 34, italics mine):

The crocus, while the days are dark,

Unfolds its saffron sheen;

At April’s touch, the crudest bark

Discovers gems of green.

Then sleep the seasons, full of might;

While slowly swells the pod

And rounds the peach, and in the night

The mushroom bursts the sod

The Winter falls; the frozen rut

Is bound with silver bars;

The snow-drift heaps against the hut;

And night is pierc’d with stars.

[12]

This is the source of Sebastian’s poetical equation of the crocus and the mushroom; one blooms in the dark days of early spring, the other in the night. That it falls under the section of poems for February is equally telling, but that its author is Coventry Patmore is the crowning detail, because the work he is most famous for is a book-length narrative poem entitled “The Angel in the House.” The cumulative impact of these details leads to the conclusion that the angel in that house is none other than Sebastian Knight himself —exerting what limited influence he has from the domain of his spectral “other world.” If it seems like a lot to ask for a poem to signify the title of another poem, it should be noted that “The Angel in the House” is significant even beyond the bounds of The Real Life. It bears a structural resemblance to Pale Fire, of which The Real Life of Sebastian Knight is a clear prototype. It consists of two main parts —the first, a single coherent poem, and the second, a series of poems written between characters, which collectively forms an epistolary novel.

On Shamoes

Chapter 24 in Ada begins with the statement that “Lettrocalamity...was banned all over the world” (147). As Vivian Darkbloom notes in the novel’s index, the word is a play on the Italian word for electromagnet, elettrocalamita (596). The reader is given to understand that electricity is altogether banned on Demonia, but what does this detail have to do with “shamoes,” a word that appears in a parenthetical aside two pages later, and which is not an actual English word? Here is the phrase from the text:

He also recalled hearing a cummerbunded Dutchman in the hotel hall telling another that Van’s father, who had just passed whistling one of his three tunes, was a famous “camler” (camel driver —shamoes having been imported recently? No, “gambler”). (149)

As others have pointed out, the word when pronounced sounds like chameau, which is the French word for camel. There is a game of words being played: shamo sounds like chameau, which is camel,

[13]

and “gambler” would sound like “camler” in Dutch-English; it is not too great an interpretive leap to associate the root word “sham” with Demon Veen. But that he was “whistling one of his three tunes” is the significant point for the present purpose.

In 1889, George Gilbert Aimé Murray wrote a novel called Gobi or Shamo: A Story of Three Songs (London: Longmans, Green, & Co., 1890). Shamo, evidently, is a regional equivalent of Gobi. But more importantly, Murray’s novel has striking parallels to Ada. It is a Lost Race novel; the protagonists, Mavrones and Baj, are seeking a lost colony of Greeks known as the Hellenes. Ada, of course, is a Lost World novel: the hunt for Terra. In Gobi or Shamo, the Hellenes’ most significant accomplishment is the harnessing of electricity, or what they call “Dynamitis,” whose primary function is to transmit messages (a procedure taken over by water in Ada). However, due to the constant threat of invasion by neighboring colonies, the energy is used as a kind of protective force field. “‘Algernon says you have found out a little about it in Europe,” says one Hellene to Mavrones and his companion, “‘you call it some name like Electro...’” (Murray 163-64). Baj finishes the word for him: “‘Electricity no doubt’” (164). Thus, an entire intricately woven theme in Ada —“the electricity theme,” as Nabokov might have said, is disguised beneath the veil of a single word taken from a little-known 19th century novel about another world.

—Steven Mihalik, New Paltz, NY

[14]

Source Of a Symbol?

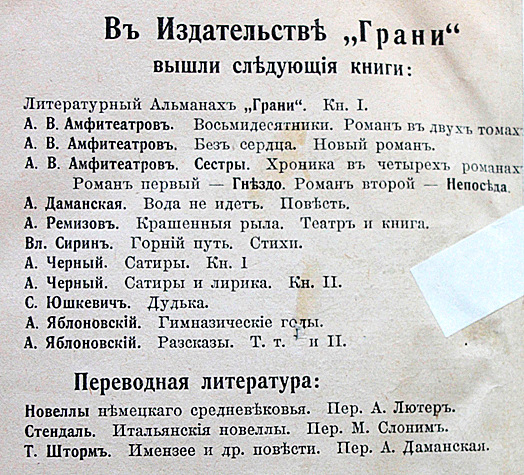

On 12 January 1924 VN wrote to Véra Slonim, “Do you know that on the cover of the first issue of ‘Grani’ our surnames are side by side? A symbol?” (Letters to Véra, Translated and edited by Olga Voronina and Brian Boyd, London: Penguin, 2014, 21). In their note to this passage the editors write, “It is unclear what VN refers to: ‘Slonim’ does not feature on the cover” (Letters to Véra, 555-556).

Yet there is a juxtaposition of surnames in Grani which, while not precisely meeting the conditions of the 12 January 1924 letter, is almost surely related to VN’s “symbol.” In the second issue, from 1923, the last printed page [264] is a page of advertisements for books appearing under the Grani imprint. The list includes “Vl. Sirin. The Empyrean Path. Poems,” and, a few inches down in a section devoted to literature in translation, “Stendahl. Italian Novella. Tr. M. Slonim.” So VN’s pen name did appear on the same page of Grani as the name of Mark Slonim, who was “remotely related” (Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton: Princeton UP, 1991, 85) to Véra. Admittedly the names do not appear on the cover of the first issue and are not in the strictest sense “side by side,” but unless a better candidate can be found, it would seem that this proximity was close enough to excite VN’s imagination.

[15]

Finally, I must note that the only copies of Grani that I have seen were rebound without the original wrappers. It is not uncommon for periodicals to print advertising copy on the inside of the wrappers. Is there a chance that the true source of the symbol is hidden on the inside cover of the first issue of Grani?

—John Hoffnagle, San Jose, California

Scent of a Woman: Olfaction Metaphors in

Vladimir Nabokov’s Novels

This paper is devoted to the way Nabokov describes smells, topically limited here to the female protagonists in his eighteen novels. The analytical method is rooted in Cognitive Metaphor Theory (G. Lakoff & M. Johnson, 2005 [1980], Metaphors We Live By, New York: Basic Books), which treats metaphors as interrelating the cognitive conceptual items of discourse with its participants and contexts. Within the schema of a cognitive metaphor, the smell impressions (source concepts) mapped onto Nabokov’s female protagonists (target concepts) by their male co-protagonists (the mapping minds) may be regarded as powerful characteristics of the latter, since “A metaphor is the result of the search for a precise epithet” in the process of “ransacking heaven and earth for a similitude” (J. Middleton Murray, The Problem of Style, London: Humphrey Milford Oxford University Press, 1936 [1922], p. 83). This method might not only reveal the peculiarities of Nabokov’s descriptive techniques but also provide insight into his masterful use of stylistic details to ensure a seamless image of his protagonists.

In female-related descriptions, Nabokov’s male characters often use natural flower smells as a source concept: VIOLETS: e.g., Luzhin’s chess board was “bathed in fragrance,” smelling, depending upon what flowers the old chess-playing gentleman brought to his aunt, “at times of violets and at times of lilies of the valley” (The Luzhin Defense, p. 55; all references refer to the Penguin series); “a whiff of violets” associated by Albinus with Margot (Laughter in the Dark, p. 32); Sonya’s “black, violet-scented hair” (Glory, p. 109); VANILLA: e.g., Emmie’s hair “smelled of vanilla” (Invitation to a Beheading, p. 65); CHESTNUT (e.g., Mariette’s hair “had a strong chestnutty smell” (Bend Sinister, p. 120) and she “had a chestnutty-

[16]

smelling bare arms” (ibid. p. 164); LAVENDER: e.g., Iris’ “lavender-scented bedroom” (Look at the Harlequins! p. 31); GRAPEFRUIT: e.g., the “grapefruit fragrance of her [Liza’s] neck” (Pnin, p. 44); HONEY: e.g., for Van, the memory of falling in love with Ada is forever linked with her eating a “tartine au miel … the classical beauty of clover honey, smooth, pale, translucent” (Ada or Ardor, p. 64); Lolita “was all rose and honey” (Lolita, p. 111); ORCHIDS: e.g. “that rapt orchideous air” in Mrs. Z.’s living room (Pale Fire, poem, lines 771-772), Van calls Ada “my phantom orchid” (Ada or Ardor, p. 155), Humbert is in awe of Lolita’s “dear dirty blue jeans, smelling of orchards in nymphetland” (Lolita, p. 91); HELOTROPE: e.g., Fyodor’s memory links his first woman with a “Turgenevian odour of heliotrope” (The Gift, p. 140). Sometimes other natural smells, those of unkempt femininity, are mentioned: e.g., when recalling his first sex partner, Van remembers “the kitchen odor of her arms” (Ada or Ardor, p. 33), and Franz recalls his sister’s “empty-stomach smell” (King, Queen, Knave, p. 1) or the “depressing, depressingly familiar odor of her [his mother’s] skin and clothes” (ibid. p. 94).

Some of Nabokov’s male protagonists seem to be knowledgeable about certain perfume labels. For instance, CHANEL, e.g., Martha’s “Chanel-scented handkerchief” (King, Queen, Knave, p. 61), TAGORE, “a cheep, sweet perfume” used by Mary (Mary, p. 63); SANGLOT, “a cheep musky perfume” worn by Mariette (Bend Sinister, p. 136); ADORATION, “a quite respectable perfume” of Ljuba Savich (Look at the Harlequins! p. 72), KRASNAYA MOSKVA or RED MOSCOW, “an insidious perfume which imbued even the hard candy” on board the Aeroflot plane (ibid. p. 162). Sometimes, perfumes are not labeled but negatively perceived, e.g. Lyudmila’s perfume is “something sleazy, stale and old” (Mary, p. 21); Margot’s “cheap sweet scent” (Laughter in the Dark, 30); “the sweet vulgar tang” of Lydia’s perfume (Despair, p. 30). Sometimes, the olfactory impression can be positive, e.g., Klara’s room “smelled of good perfume” (Mary, 42); Claire used “a nice cool perfume” (The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, p. 61), while Fyodor is pursued by “the smell of that certain scent which somehow was always used by the very women who liked him, although to him this dullish, sweetish-brown smell was unbearable” (The Gift, p. 153).

Nabokov often describes complex odors, of which perfume is but a constituent. For instance, Humbert writes that Lolita’s bed

[17]

“smelled of chestnut and roses, and peppermint, and the very delicate, very special French perfume I lately allowed her to use” (Lolita, p. 239). Annabel’s scent is described as combining the odor of “some kind of toilet powder” and “a sweetish, lowly, musky perfume … mingled with her own biscuity odour” (ibid. p. 15). Mona Dahl’s skin scent that Humbert “made out through lotions and creams” is called “uninteresting” (ibid. p. 189), while Ganin admires Mary’s “blur of cool fragrance, a blend of perfume and damp serge, that fragrance of hers” (Mary, p. 69). Among Nabokov’s characters there are highly temperature-sensitive male protagonists, e.g. Cincinnatus describes Emmie’s “cold fingers and hot elbows” (Invitation to a Beheading, p. 126), while Van writes about Ada, “Her hands were cold, her neck was hot” (Ada or Ardor, p. 103).

More than once Nabokov’s male protagonists are disgusted by what the writer describes as “a smell of scent and sweat” (Laughter in the Dark, p. 187). The description can be brief, e.g. “His secretary, Dora Wittgenstein […] smelling of carrion through her cheap eau de cologne” (The Gift, p. 176), or finely detailed, as, for instance, in VV’s reaction to Ljuba Savich’s composite smell:

I began to notice with growing irritation such pathetic things as her odor, a quite respectable perfume (Adoration, I think) precariously overlaying the natural smell of a Russian maiden’s seldom bathed body: for an hour or so Adoration still held, but after that the underground would start to conduct more and more frequent forays, and when she raised her arms to put on her hat—but never mind … (Look at the Harlequins! p. 72).

In the same novel, the protagonist starts his trip to Russia with the following observation: “It was a very warm day in June and the farcical air-conditioning system failed to outvie the whiffs of sweat and the sprayings of Krasnaya Moskva” (ibid. p. 162) emanating from a stewardess; that air servant was replaced by “a still fatter stewardess, in a still stronger aura of onion and sweat” (ibid. p. 163), and the unfortunate protagonist was pursued by the “mixed odors of dour hostess and ‘Red Moscow,’ with a gradual prevalence of the first ingredient” (ibid. p. 164) throughout his trip. Sometimes such “mixed odors” may, however, be irresistibly attractive for a male

[18]

protagonist, e.g. the smell of Lolita’s unwashed hair is “intoxicating” for Humbert (Lolita, p. 43).

The sense of smell can be combined with that of taste, e.g., Cincinnatus recalls Marthe’s “rosy kisses tasting of wild strawberries” (Invitation to a Beheading, p. 25), or Humbert’s sharp Lolita-attuned senses make him write that in a kiss they “shared the peppermint taste of her saliva” (Lolita, p. 113), or “her brown rose tasted of blood,” and “her breath was bittersweet” (ibid. p. 238). The sense of smell can also be combined with that of thermoception, e.g., Martin could feel the warmth of Sonia’s hair and “a waft of delicate warmth [that] emanated from her” (Glory, p. 91), Humbert mentions “that singular warmth emanating from her [Lolita]” (Lolita, p. 213) and that he could feel “the aura of her bare shoulder like a warm breath upon my cheek” (ibid. p. 130); Matilda’s body “exuded a generous warmth” (The Eye, p. 14), while Martha’s lips were “fragrant, warm-looking” (King, Queen, Knave, p. 59).

Nabokov’s metaphors of smell are often inventive: they may use an imaginary source concept, e.g., Martha’s coat lining “smelled of heaven” (King, Queen, Knave, p. 95); they can employ unorthodox associations, e.g., Lolita’s kiss was “sweet wetness and trembling fire” (Lolita, p. 112), or Franz sees Martha as “coldly radiant” (King, Queen, Knave, p. 105); they can be exact to the level of subtle undertones, e.g., “she [Lolita] smelt almost exactly like Annabel but more intensely so, with rougher overtones” (Lolita, p. 42) or “Dolly-smell, with a faint fried addition” (ibid. p. 268); they can be colored, e.g., for Humbert Lolita’s smell is “brown fragrance” (Lolita, p. 43) or for Cincinnatus Marthe’s kisses are “rosy” (Invitation to a Beheading, p. 25); they can be overtly sexual, e.g., Lolita’s “wenchy smell” (Lolita, p. 202).

The repetitive olfactory metaphors in Nabokov’s novels are always character-related. As has been shown above, negative olfactory impressions may manifest the protagonists’ dislike, sometimes subconscious, of the bearers of the smell, e.g. Ganin’s for Lyudmila, VV’s for Ljuba, or Hermann’s for Lydia. Albinus is fully aware of Elizabeth’s merits but his fatal attraction to Margot leads him to prefer her “cheap sweet scent” (Laughter in the Dark, p. 30) to the exquisite “faint scent of his wife’s eau-de-Cologne” (ibid. p. 78). Or, for instance, after Maria, the seventeen-year old servant girl, left the room, Martin’s mother “sniffed the air, made a face, and hurriedly opened all the windows” (Glory, p. 51), which immediately

[19]

dispelled Martin’s fascination with the girl, thus attesting to his suggestibility; Gruzinov also immediately opened the windows after his heavily perfumed wife left their hotel room (ibid. p. 162), which reveals his diplomatic skills later confirmed by the instructions for border crossing he gave to Martin. Cincinnatus claims that his “sense of smell [is] like a deer’s” (Invitation to a Beheading, p. 45), but in addition to his wife’s “rosy kisses” (ibid. p. 25) he mentions just one more female smell: Emmie’s hair that “smelled of vanilla” (ibid. p. 65), which adds to the surrealism of the novel’s “invented habitus” (ibid. p. 32). A close look at even one stylistic detail of the majestic gestalt tapestry of Nabokov’s writing technique substantiates the organic unity of his style.

— Ljuba Tarvi, Helsinki

Despair Disassociated

1

In The New Yorker (December 4 2014) John Colapinto described his visit to the “frigid reading room” of the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection, where he examined Vladimir Nabokov’s personal copy of Camera Obscura. The novel was the sixth that Nabokov wrote in his “infinitely docile Russian tongue,” and in 1936, scornful of its English translation, he retranslated it himself and renamed it Laughter in the Dark. Readers have long detected the dim figures of a more canonical couple morphing from the shadows of Albert Albinus and Margot Peter, its focal duo: he, a middle-aged art critic, she, his sixteen year-old seductress. The copy Colapinto read is the copy in which Nabokov made his significant revisions of the text. They amount to an unusual case study for genetic criticism, and provide, Colapinto writes, “an unmediated look at the Master at work, removing dead and dull passages, fixing inept or lame plot developments, eradicating longueurs, and seeking out opportunities to sharpen imagery or provide deeper insight into a character’s motivation”(http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/nabokov-retranslated-laughter-dark).

[20]

Nabokov’s personal copy of Despair (originally Otchayanie), the novel that preceeds Camera Obscura, is housed in the Berg Collection too, and possesses a back-story parallel, in various ways, to Laughter in the Dark’s. The trans-national genesis of the English-language text now in print involves not only serialization, public readings, translation and revision, but Nazis, bombs, and a rise from penury to fame. Here is a summary.

At the end of August 1932 Vladimir and Véra Nabokov took two rooms in a third floor flat at 22 Nestorstrasse in Berlin’s Wilmersdorf district. It was there, on September 10th, after only forty-two days of writing, that Nabokov finished the first draft of Otchayanie. The story of Hermann Hermann, who during a trip to Prague meets a tramp called Felix whom he believes to be his exact likeness and so hatches a doomed plan to buy life insurance, dress his double in his clothes, shoot him, and meet his wife and the insurance money in France, is a treatment of the perennial Nabokovian theme of art and life’s intersections, as well as a Dostoevskian parody with a protagonist whose criminal-artistry is an ignis fatuus and whose spiritual redemption never arrives.

After completing the first Russian draft, Nabokov travelled to Paris to conduct a reading tour that would provide Otchayanie with its first audience. He was a great hit in Russian émigré circles, having ascended in estimations to the top of their literature. Between social calls he revised Otchayanie. Brian Boyd richly narrates these episodes in The Russian Years. He tells of the motherly Amalia Fondaminsky with whom Nabokov roomed in November, who “typed up the thirty odd pages of Despair—its revision just completed—that he planned to read,” and of the novel’s first public airing on November 14th at the Musée Sociale, 5 rue Las Cases, where Nabokov recited its first two chapters to a crowd he described as “a great, kind, sensitive, pulsing beast that grunted and guffawed at the places I needed it, and again obediently fell silent,” and which congratulated him extensively and ordered advance copies in a café once the reading had finished.

When he returned to Berlin, Véra transcribed the text. The novel was serialized throughout 1934 in the émigré review Sovremennye Zapiski. The German publishers Petropolis published the book in 1936. Money was a continual difficulty for the Nabokovs in Berlin and translations of Vladimir’s Russian novels assured valuable income. After suffering the disappointment of the “loose, shapeless,

[21]

sloppy” translation of Camera Obscura, Nabokov decided to translate Otchayanie himself. In his introduction to the 1965 edition he explained,

At the end of 1936, while I was still living in Berlin…I translated Otchayanie for a London publisher. Although I had been scribbling in English all my literary life in the margin, so to say, of my Russian writings, this was my first serious attempt to use English for what may be loosely termed an artistic purpose. The result seemed to me stylistically clumsy, so I asked a rather clumsy Englishman…to read the stuff; he found a few solecisms in the first chapter, but then refused to continue, saying he disapproved of the book. (vii)

Nabokov found the task trying, writing to a friend that “to translate oneself is a frightful business, looking over one’s insides and trying them on like a glove.” And then, after the exertion, in 1936,

John Long Limited, of London, brought out Despair…the book sold badly, and a few years later a German bomb destroyed the entire stock. The only copy extant is, as far as I know, the one I own —but two or three may still be lurking amidst abandoned reading matter on the dark shelves of seaside boarding houses from Bournemouth to Tweedmouth. (vii)

Nabokov’s extant copy did well for itself, and has settled on 5th Avenue, in the Berg Collection. Yet before arriving in the archive it acquired new significance.

Having fled St. Petersburg and the Bolsheviks in 1917, Nabokov, with the extant copy of Despair in his luggage, fled Paris and Hitler in 1940. After arriving in America, Nabokov took pains to become an American author, abandoning his Russian tongue (“my private tragedy”) for his new marketplace. The apex of his success came with Lolita in 1958, and with burgeoning public interest his oeuvre expanded backwards. Often with the assistance of his son Dmitri, he translated his Russian works. Yet Despair stood peculiarly among

[22]

them. With Laughter in the Dark, it was the only member of his Russian period to have been translated by its author and published in book form. Yet in this form it was all but extinct.

The compositional approach Nabokov took to the republication of the English Despair marks an uncommon genetic event. Nabokov used his 1936 edition as a sort of typescript and made two hundred and eighty-seven pencil alterations in the margins of the book. Neatly parenthesizing the sections of text he wished to be removed and linking them with thin lines to the additions, his minor alterations (usually substitutions) tend to be made in either the margins (usually horizontally, occasionally vertically) or within the text, while longer additions often occupy the space at the bottom of the page, or in the case of an especially long paragraph to which we’ll return, on blank sheets at the beginning of the book. His changes marked a major revision, made in maturity, of a text thirty years old.

2

Many of Nabokov’s revisions for his 1965 edition of Despair are of a literal-minded nature. That is, many update certain words and phrases to align with American idioms (“bathing pants” becomes “swimming trunks,” for instance) and into these we can read a self that altered over time and produced fiction in vastly different milieux. It is adequate to interpret other revisions as simple improvements of expression (“kind of Scotch-looking” becomes “pseudo-Scotch,” “bristly-shaded” becomes “bristle-shaded”) and others, as formal alterations, which Jane Grayson, in her 1977 study Nabokov Translated: A Comparison of Nabokov's Russian and English Prose (still the authority on Nabokovian revision) helpfully elucidated. In that book Grayson stresses that the first English version of Despair “makes only minor alterations to the Russian,” while in the 1965 version there are a number of “significant additions to the original text” that “affect structure, character and style” (26). Those revisions offer considerable scope for interpretation beyond the insights of Nabokov Translated; an ideal starting point for that is a passage of text that was written for, though excluded from, the original novel, and that Nabokov re-inserted in 1965.

In his ludic introduction of 1965 Nabokov explains: “lucky students who may be able to compare the three texts will note the

[23]

addition of an important passage which had been stupidly omitted in more timid times” (vii). It can be deduced that the passage to which Nabokov refers is the description of “dissociation” that he inserted into page forty of his 1936 copy. Pivotal, and a thematic guide to a range of other revisions, it is by far the longest (Nabokov filled the blank pages 5, 6 and 7 of the book with it, and linked it to its place with an asterisk) and by far the bluest. Hermann describes a psychological phenomenon he has been experiencing while in bed with his wife, Lydia, that he names “dissociation.” While his face, Hermann says, was “buried in the folds of [Lydia’s] neck, her legs had started to clamp me…but at the same time, incomprehensibly and delightfully, I was standing naked in the middle of the room.” The sensation of “being in two places at once” allows him to admire his own “muscular back” in the “laboratorial light” of his “magical point of vantage.” He refers to himself as “the audience,” and comes to realize that “the greater the interval between my two selves the more I was ecstasied,” so retreats further each night until he finds himself “sitting in the parlour—while making love in the bedroom,” longing to distend from the “lighted stage where I performed.”

This “important” paragraph reveals an important dichotomy, the presence of which alters the texture of the edition we now read. Hermann’s sensation is one of physical and cerebral separation. While his body acts, his mind watches. He is present in the situation, yet his perspective on it is removed, a room away. And, Nabokov hints, his perspective is not merely removed, but inaccurate and self-deceiving. After bragging of the ease with which he could “bundle Lydia to bed,” the only time we sight his wife, among the mist of Hermann’s self-admiration, she yawns and asks to be brought a book.

John Colapinto describes how, when revising Camera Obscura, Nabokov “seized on a single phrase on page fifteen…an aside about Albinus’s idle musings about financing a film of a picture by Rembrandt or Goya,” moved it to the beginning of the book, and expanded it into a “long, strikingly visual paragraph about an animated Bruegel that sweeps the reader into the story.” Nabokov reignited the novel with that passage. And in Despair it is a single substantial amendment that again proved the catalyst of a major revision. The vignette of sexual dissociation, of a mind askance of its body, became crucial to Nabokov’s portrait of Hermann’s insanity, and many of the 1965 revisions mimic its premise. In her 2013 book

[24]

The Work of Revision, Hannah Sullivan chronicles “Bloom’s expanding mind”—the cognitive amplitude that Joyce’s revisions of Ulysses piled onto his hero. In the case of Despair we have Hermann’s distorting mind, becoming not “more scattered and curious,” like Bloom’s, but more detached. Nabokov’s re-insertion of the “dissociation” passage provided his revisions with their emblem.

The revisions have a twin purpose: they intensify dramatic irony and they develop Hermann’s psychology. For instance, Nabokov inserts a number of allusions to the affair between Hermann’s wife and Ardalion. Take the addition, “[H]er lipstick strayed to incomprehensible places such as her cousin’s shirt pocket.” This sentence demonstrates, in miniature, the dynamic initiated by the important passage. It is a discreet expression of dissociation. Nabokov shows us that Hermann is physically present yet mentally removed. The adjective “incomprehensible” is trenchant, conveying that the world in which Hermann abides does not align with that which he sees (this is the comedy of one word, rather than Joyce’s “One Word More,” to which Sullivan gestures). Hermann’s psychology, the addition suggests, disallows any sort of cognitive mastery of objective visual evidence. Rather than comprehending its semiotic import he distances himself, just as he did on hearing Lydia’s bored request for a book. This technique is evident again when Hermann longs for a hot bath, before “wryly correcting anticipation with the thought that Ardalion had probably used the tub as his kind cousin had already allowed him to do.” The revision stretches a comic distance between knowledge and acceptance.

Copious examples conform to this pattern. Into the 1965 edition, for instance, Nabokov inserted the following line as Hermann’s justification for shaking Felix’s hand: “I grasped it only because it provided me with the curious sensation of Narcissus fooling Nemesis by helping his image out of the brook.” In the Ovidian myth, Nemesis leads Narcissus to his reflection in a pool, which Narcissus falls in love with and cannot leave, so dies. The story offers an image of the split self and an allegory of self-deception. Consistent with the motifs of dissociation with which Nabokov besets him, Hermann revises the story so that the self is in fact duplicated, and exists, as in those coital migrations, in mutually adoring doubleness.

Nabokov gave Despair a new dénouement, a final paragraph that Hermann shouts from the window of the house in which he’s hiding,

[25]

surrounded by policemen. The speech demonstrates Hermann’s final act of dissociation. He recasts himself as a film star:

This is a rehearsal. Hold those policemen. A famous actor will presently come running out of this house. He is an arch criminal but must escape. You are asked to prevent them getting him. This is part of the plot…Attention! I want a clean getaway. That’s all. Thank you. I’m coming out now. (163)

Hermann retreats into celluloid fantasia. Where, in his “furious dissociations” with Lydia, he had imagined himself as audience to himself, when his evasion of the authorities reaches its conclusion he dissociates himself with the reality to the extent that his captors become his audience and his film crew, and his charge from the house a stunt, an element of plot. This revision, the final image of Hermann’s insanity, depicts his division, and its conceptual basis finds its clearest expression, indeed its definition, in the reinserted passage of page forty—in 1936 excised, but from 1965 instrumental to the novel that we read today.

—Luke Maxted, London