Download PDF of Number 67 (Fall 2011) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 67 Fall 2011

__________________________________

CONTENTS

News 3

by Stephen Jan Parker

Notes and Brief Commentaries 7

by Priscilla Meyer

“Tennis References in The Original of Laura” 7

– Gavriel Shapiro

“Lolita's Ape, Caged at Last!” 14

– Stephen Blackwell

“Sebastian Through the Looking Glass” 20

– Zachary Fischman

Annotations to Ada 33: Part I Chapter 33 32

by Brian Boyd

Annotations to Ada 34: Part I Chapter 34 49

by Brian Boyd

2010 Nabokov Bibliography 60

by Sidney Eric Dement

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 67, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

In some but not all cases the downloadable pdf version of the print Nabokovian will have the annual bibliography and the “Annotations to Ada.”

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nabokov Society News

The membership/subscription figures in 2011 have risen to the same level they were one year ago. Unfortunately that amount of membership/subscription payment is now insufficient because of the significant increase in postage and printing services costs over the past several years. So we have reached the point of either significantly increasing the number of members, membership/subscription fees, or simply ceasing the existence of the Vladimir Nabokov Society and The Nabokovian and allowing all Nabokov activities to appear on a computer. I created The Nabokovian and the Vladimir Nabokov Society 33 years ago and it may be that both have now reached the age of retirement. To this point we have survived largely because of the stable members/subscribers and the regular, magnanimous monetary contributions of our dearest friend, Dmitri Nabokov. Thus the Nabokov Society members will soon have to come to a decision on what is to be done.

* * * *

Odds & Ends

1. Brian Boyd has edited Pale Fire: A Poem in Four Cantos by John Shade (Berkeley, CA: Gingko Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-58423-431-9), a “volume” which seeks to focus on the poem as poem, rather than as part of the novel Pale Fire, and to understand it as Shade’s and Nabokov’s accomplishment. The project, initiated by artist Jean Holabird, consists of 50 index cards, as if Shade’s manuscript of the poem, and following all the

[4]

details recorded by Kinbote; a booklet of the poem, illustrated by Jean Holabird; and a booklet of essays (also illustrated by Holabird), one by Brian Boyd, on the poetic achievement of the poem, and the other by poet R. S. Gwynn, on “Pale Fire” within the context of American poetry, and especially long autobiographical poems, written at the end of the 1950s and early 1960s. For details and images, see

http://www.gingkopress.com/09-lit/vladimir-nabokov-pale-fire.html.

Brian Boyd has also published a selection of his essays on Nabokov, Stalking Nabokov: Selected Essays (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 464 pages, ISBN 978-0- 231-15856-5. Details can be found at http://cup.columbia.edu/book/978-0-231-15856-5/stalking-nabokov. It includes essays written over many years, from 1990 to 2010, on many facets of Nabokov’s life and work, with occasional glimpses of Boyd’s pursuit of Nabokov. There are sections on:

Nabokov: The Writer’s Life and the Life Writer: 1. A Centennial Toast (1999); 2. A Biographer’s Life (2001); 3. Who Is “My Nabokov”? (2007);

Nabokov’s Manuscripts and Books: 4. The Nabokov Biography and the Nabokov Archive (1992); 5. From the Nabokov Archive: Nabokov’s Literary Legacy (2009);

Nabokov’s Metaphysics: 6. Retrospects and Prospects (2001); 7. Nabokov’s Afterlife (2002);

Nabokov’s Butterflies: 8. Nabokov, Literature, Lepidoptera (2000); 9. Netting Nabokov: Review of Dieter E. Zimmer, A Guide to Nabokov’s Butterflies and Moths, 2001 (2001);

Nabokov as Psychologist: 10. The Psychological Work of Fictional Play (2010);

Nabokov and the Origins and Ends of Stories: 11. Stacks of Stories, Stories of Stacks (2010);

Nabokov as Writer: 12. Nabokov’s Humor (1996); 13. Nabokov as Storyteller (2002); 14. Nabokov’s Transition from

[5]

Russian to English: Repudiation or Evolution? (2007);

Nabokov and Others: 15. Nabokov, Pushkin, Shakespeare: Genius, Generosity, and Gratitude in The Gift and Pale Fire (1999); 16. Nabokov as Verse Translator: Introduction to Verses and Versions (2008); 17. Tolstoy and Nabokov (1993); 18. Nabokov and Machado de Assis (2009); and

Nabokov Works: 19. Speak, Memory: The Life and the Art (1990); 20. Speak, Memory: Nabokov, Mother, and Lovers: The Weave of the Magic Carpet (1999); 21 .Lolita: Scene and Unseen (2006); 22. Even Homais Nods: Nabokov’s Fallibility; Or, How to Revise Lolita (1995); 23. Literature, Pattern, Lolita; Or, Art, Literature, Science (2008); 24. “Pale Fire”: Poem and Pattern (2010); 25. Ada: Thee Bog and the Garden; Or, Straw, Fluff, and Peat: Sources and Places in Ada (2004); 26. A Book Burner Recants: The Original of Laura (2010).

Each essay has a brief introduction, setting out the circumstances of its composition and delivery or publication. The volume is dedicated “To my friends in the Nabokov world.”

An interview with Brian Boyd about the book appears on the book website:

Rorotoko, atrorotoko.com/interview/20111108 boyd brian on stalkina nabokov.

Anyone in North America who uses the promotional code “STABO” to buy the book from the Columbia website will receive a 30% discount off the price of the book. Anyone in Australia or New Zealand who buys through the local distributor will receive a 15% discount: http://www.footprint.com.au/. Purchasers will need to enter the code SN1011 when they check out after they have finished shopping on the Footprint website.

2. Many new images hyperlinked to the annotations have been added to Brian Boyd’s ADA Online website, http://www.ada.auckland.ac.nz/. which includes updated versions of the “Annotations to Ada” first published in The Nabokovian, two years behind the journal publication (so that the latest online is Part 1 Chapter 30). By the time this issue appears, all chapters through

[6]

Part 1 Chapter 25 should have a complete set of illustrations. Since the illustrations are indexed numerically by page and line number, as well as alphabetically by subject, readers can as it were do a visual skim through ADA by clicking on Images on the top bar, clicking on Index by Page/Line Number, and clicking on each link.

3. An advance instalment of Nabokov’s Letters to Véra, being translated and edited by Olga Voronina (Bard College) and Brian Boyd, appeared as “The Russian Professor,” New Yorker, June 13 and 20 2011, 100-04. Letters to Véra should be published in 2013.

4. The international conference on Vladimir Nabokov that Brian Boyd is organizing at the University of Auckland for January 10-13,2012 now has a website, http://www.nabokov2012.co.nz/ (see, for a surprising view of Nabokov). Registration is still open. Speakers from Brazil, Canada, England, France, Japan, New Zealand, Scotland, and the US will follow the keynote speaker, Robert Alter (Berkeley).

* * * *

As I have done for the past 32 years, I wish once again to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential, remarkable on-going assistance in the production of this publication.

[7]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to Priscilla Meyer at pmeyer@wesleyan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format. All contributors must be current members of the Nabokov Society. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Notes may be sent, anonymously, to a reader for review. If accepted for publication, some slight editorial alterations may be made. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (footnotes incorporated within the text, American punctuation, single space after periods, signature: name, place, etc.) used in this section.

TENNIS REFERENCES IN THE ORIGINAL OF LAURA

Vladimir Nabokov was an avid tennis player and fan throughout his entire life. This passion for the sport is reflected in his oeuvre that abounds with tennis episodes. Suffice it to mention the poems “Lawn Tennis,” “A University Poem,” the novels Glory and Lolita. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that his last novel, too, contains a number of tennis references and allusions.

In The Original of Laura, there is a passage which describes Flora, while in Cannes, “taking her tennis lessons with the stodgy old Basque in uncreased white trousers who had coached players in Odessa before World War One and still retained his effortless exquisite style” (TOOL 81). It appears that Flora’s coach has real

[8]

prototypes. Most obvious among them is Joseph Negro. In his Nice letter to Roman Grinberg of February 23,1961, Nabokov writes: “I play here with a professional [named] Negro who once coached in Russian tennis clubs, for example, in Odessa before World War I! A wonderful semi-lame swarthy old man who comes to life on court like cactus breaking into blossom” (“Igraiu tut s professionalom Negro, kotoryi kogda-to uchil v russkikh tennisnykh klubakh, napr<imer> v Odesse do pervoi voiny! Chudnyi polukhromoi smuglyi starik, kotoryi ozhivaet na ploshchadke, kak zatsvetshii kaktus”); see Rashit Iangirov, publ., “Druz'ia, babochki i monstry. Iz perepiski Vladimira i Very Nabokovykh s Romanom Grinbergom [1943-1967],” Diaspora 1 (2001): 534). One wonders why Nabokov did not employ this magnificent cactus simile in The Original of Laura. Did he forget all about it, or did he find it to be literally too florid for the description of this fleeting character, or would he have used it in later drafts of his last novel? We shall never know.

Who was this man who served as the principal prototype for Flora’s tennis instructor? Joseph Negro was bom in Badalucco, a tiny township in the Liguria region of Italy. In 1902, his family emigrated to nearby Nice. “As a child, the barefoot Negro would fetch tennis balls for the members of the club. Yet soon his natural talent helped him become first a [ball] tosser, and than an instructor” (Gianni Clerici, Divina: Suzanne Lenglen, la più grande tennista del XX. secolo, Milan: Casa Editrice Corbaccio, 2002,29). It is at that time, in January of 1912, that Negro became and remained the life-long coach of Nabokov’s coeval—the great Suzanne Lenglen (1899-193 8) (see Lily Wollerner, “Breve rencontre avec M. Negro doyen des professeurs azureens,” Nice-Matin, December 3, 1966, 4). “Negro’s game was full of tricks and surprises, spins and slices. One amazed spectator concluded of Negro’s abilities: ‘If you told me he could make the ball sit up and beg, I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised.’ Negro was nothing less than a sorcerer of tennis, and little Suzanne became his studious apprentice” (Larry Engelmann,

[9]

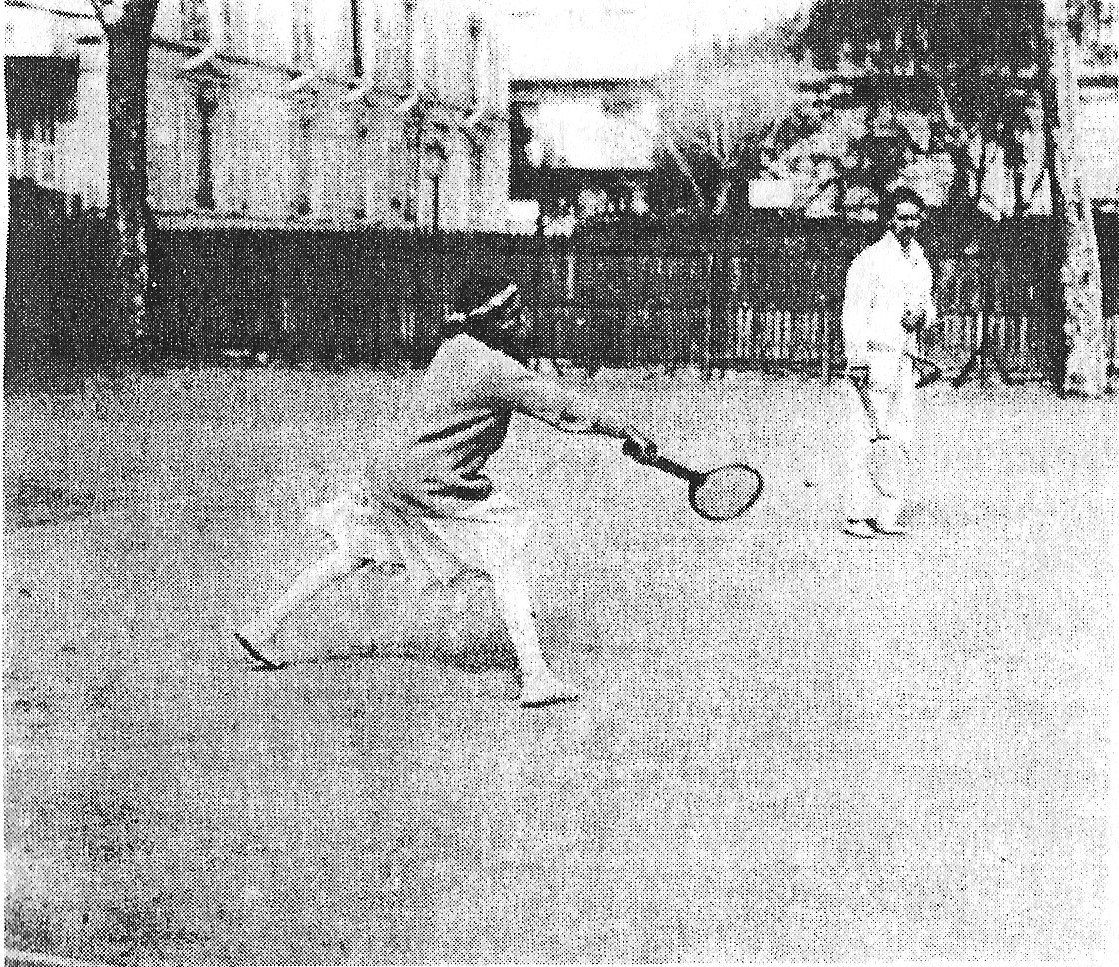

The Goddess and the American Girl: The Story of Suzanne Lenglen and Helen Wills, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, 11-12). There exists a rare photograph that shows the adolescent Suzanne Lenglen practicing her backhand under the watchful eye of Joseph Negro at the Place Mozart Tennis Court in Nice (source: Clerici, Divina, 30).

Negro was such a good coach “that an aristocratic Russian family hired him and during the summer months took him with them to Odessa” (Clerici, Divina, 29). In 1912, two lawn-tennis clubs were founded in the city—the Odessa British Athletic Club (Odesskii Britanskii Atleticheskii Klub) and the Odessa Lawn-Tennis Club (Odesskii Laun-Tennis Klub) (see Boris Fomenko, Rossiiskii tennis: Entsiklopediia, Moscow: IETP, 1999, 145). The clubs were evidently in need of instructors, and Joseph Negro, in addition to coaching the “aristocratic

[10]

Russian family,” was presumably teaching tennis in Odessa to members of these clubs at that same time. Hence Nabokov’s aforementioned notion that “Negro coached in Russian tennis clubs [...] in Odessa before World War I.” During the War, Negro was sent to the Italian front where he had been wounded in the leg, and remained, at least for a while, “limping because of his wound” (Clerici, Divina, 59 and 64). Apparently his leg sufficiently healed over the course of several years, so much so that Negro became a two-time finalist of the Bristol Cup (1922 and 1923), the most prestigious professional tournament of the time, also known as the French Pro <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Pro_Championship>. In the late 1930s, Negro is listed as a Professor of

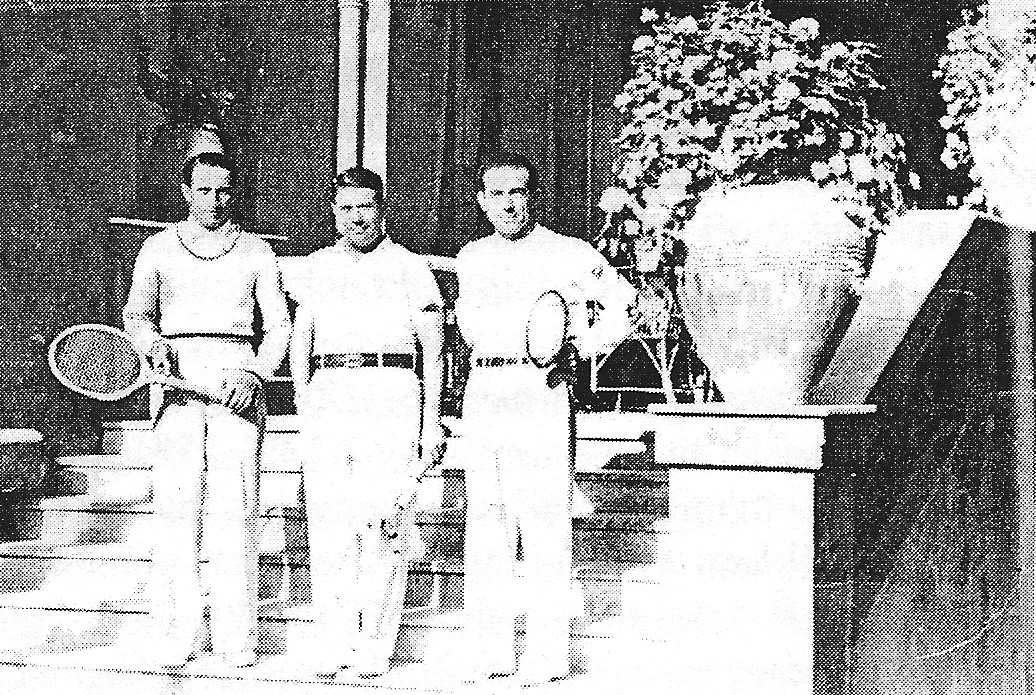

A. F. P. P. T.—the French Association of Tennis Professors and Professionals—alongside such greats as Romeo Acquarone, Henry Cochet, Henri Darsonval, and Martin Plaa (see Philippe Brossard, Prof ou champion de tennis: tennis-études et sélections pour futurs champions. Comment devenir prof de tennis, Paris: Editions EDICIS, 1991, between 112 and 113). Another rare photograph depicts Negro as a tennis instructor at the Nice Lawn Tennis Club. The caption reads: “Three distinguished professors who have marked the life of the Nice Lawn Tennis Club: André Curti, Joseph Negro, Victor Broccardo. They reigned for nearly three quarters of a century” (photo courtesy of the Nice Lawn Tennis Club.) When Nabokov met Negro in Nice in 1961, the old war wound apparently made itself felt once again. Negro was limping, prompting Nabokov to call him in his letter to Grinberg a “semi-lame old man.”

When composing The Original of Laura some fifteen years after meeting Negro in Nice, Nabokov changed the Riviera site from Nice to Cannes. Furthermore, after apparently browsing through the Southern France resort cell of his memory [from Côte d’Azur to Côte des Basques] and recalling his childhood Biarritz impressions, and particularly “[Professional bathers, burly Basques” (SM 148), he decided to bestow instead that

[11]

Trois professeurs célèbres qui ont marque la vie du Nice L.T.C.: Andre Curti, Joseph Negro, Victor Brocardo. Ils ont régné pendant près de trois quarts de siècle.

nationality upon Flora’s tennis coach. Another “burly Basque” was a renowned boxer Paolino Uzcudun whose match with Hans Breitensträter Nabokov reviewed in his 1925 essay. In this essay on boxing Nabokov likens human activities to a game and mentions tennis as one of the examples: “Everything good in life—love, nature, the arts and home calembours—is a game. And when we indeed play—whether we smash a tin battalion with a pellet, or face one another across the tennis cord barrier—we sense in our very muscles the essence of the game in which is engaged the wondrous Juggler who tosses planets of the universe from hand to hand in an uninterrupted sparkling parabola” (“Vse khoroshee v zhizni: liubov', priroda, iskusstva i domashnie kalambury—igra. I kogda my deistvitel'no igraem—razbivaem li goroshinkoi zhestianoi batal' on ili skhodimsia u verevochnogo bar' era tennisa, to v samykh myshtsakh nashikh oshchushchaem sushchnost' toi igry, kotoroi zaniat divnyi zhongler, chto perekidyvaet iz ruki v ruku bespreryvnoi sverkaiushchei paraboloi—planety vselennoi”) (Ssoch, 1: 749). Perhaps this boxing—tennis association by

[12]

way of the game paradigm was another reason for Nabokov’s making this fleeting character a Basque.

Moreover, there were two renowned Basque tennis players of whom Nabokov undoubtedly knew. One, the Biarritz-born Jean Borotra (1898-1994), nicknamed “the Bounding Basque,” a two-time Wimbledon champion (1924, 1926), a two-time French Open champion (1924 and 1931), and an Australian Open champion (1928) (see Jean-Pierre Chevallier, Le tennis en France, 1875-1955, Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire: Alan Sutton, 2007, 127; for Borotra’s biography, see Sir John Smyth, Jean Borotra, the Bounding Basque: His Life of Work and Play, London: Stanley Paul, 1974). The other prominent Basque player, nicknamed “the Basque Professor,” was the earlier – mentioned Martin Plaa (1901-78), the winner (1931) and two-time finalist (1932 and 1934) of the French Pro. In 1932, Plaa was the winner of the clay-court World Pro Championship, held in Berlin, in which he defeated both the distinguished clay-court specialist Hans Nüsslein and the celebrated Bill Tilden to whom Nabokov alludes in Lolita (AnL 162 and 232). The tournament was played at the Rot-Weiss Club in Grunewald, September 20-26, and Nabokov, with his fondness for tennis, could easily attend the tournament, or at least follow it in the newspapers. Plaa was short in stature and somewhat heavy-set (see <http://www.tennisserver.com/lines/lines_02_10_05.html>), and Nabokov, perhaps, had Plaa’s nationality and physical attributes in mind when describing “the stodgy old Basque” in The Original of Laura. (For a brief account of Plaa’s life see his obituary in New York Times, March 30, 1978, B2.)

The Original of Laura contains at least two more tennis allusions. The first is in the mention of “the Carlton Courts in Cannes” (TOOL 77) where Flora’s first lover, Jules, served as a ball boy and where she had lessons with the “stodgy old Basque” coach. It is at the Carlton Club in Cannes that on February 16, 1926, the so-called Match of the Century was held in which Suzanne Lenglen defeated Helen Wills (1905-98), herself a

[13]

great champion and the first American-born woman athlete to attain an international celebrity status. (For a detailed account of this match, see Engelmann, The Goddess and the American Girl, 154-86). Nabokov, an enthusiastic tennis player and fan, undoubtedly followed this event. As we recall, Humbert acquires for Lolita a coaching manual, Tennis, by Helen Wills. He correctly identifies Wills as the winner of “the National Junior Girl Singles at the age of fifteen” (AnL 242) and presumably mentions her early accomplishment in the hope that, given the talent, Lolita will replicate the feat and will follow the suit of the great champion.

Finally, it is likely that by relocating Flora, an active tennis player, to “Sutton, Mass.,” in which she matriculates at “Sutton College” (TOOL 89-90), Nabokov planted an additional tennis connotation. Although “Sutton, Mass.” does exist, a small township that numbered less than 5,500 inhabitants in 1975, it has no college. It is likely therefore that with Sutton College Nabokov pays tribute to the Sutton sisters all four of whom were very accomplished tennis players at the turn of the twentieth century, and especially to May Sutton (1886-1975), the most celebrated among them, who was the first American female tennis player (albeit English-born) to win Wimbledon (1905 and 1907). (To be sure, Nabokov employs the surname in his earlier works: in the story “Time and Webb” [1944], in which Dr. de Sutton is mentioned [Stories 585], and repeatedly in Pale Fire [1962], as, for example, in reference to “Old Dr. Sutton’s last two windowpanes” [PF 69]). Perhaps while working on his last novel in 1975, Nabokov came across May Sutton’s obituary and decided to commemorate her passing by naming the New England College after her.

I am greatly indebted to Kora Bättig von Wittelsbach of Cornell University for her invaluable assistance with sources and in correspondence with various institutions in French and Italian.

—Gavriel Shapiro, Ithaca, New York

[14]

LOLITA’S APE, CAGED AT LAST!

1939 was a good year for bars and for barmen. Not neighborhood bars, but the bars of a cage or prison cell; the barman was Nabokov. It was in this year that Nabokov, according to his recollection, began thinking about the cage-like qualities of an individual’s phenomenal reality. Although the motif of imprisonment (including solipsistic imprisonment) can be found in Nabokov’s works at least as early as Despair, recurring in Camera Obscura, Invitation to a Beheading, and The Gift in the middle 1930s, it was apparently in 1939, or thereabouts, that Nabokov developed in his mind the idea of human conscious life as itself a kind of prison- or zoo-like enclosure. In his essay “On a Book Entitled Lolita,” he famously claimed that his novel’s “first shiver” was inspired by an artistic ape at Paris’s Jardin des plantes, allegedly reported in newspapers in 1939 or -40: the first non-human, Nabokov said, ever to create a representational drawing, which turned out to be the bars of its cage (Annotated Lolita, 311). As Nabokov explained in his 1958 Canadian Broadcast Service interview with Pierre Burton and Lionel Trilling, the idea of the animal’s cage corresponds to the world of nymphets as conceived by Humbert Humbert: the pedophile’s imaginary world is his prison, isolating him from the “real” world of autonomous individuals and their needs. So much is clear. Less clear is the source of the reference to this sad, creative ape: annotators have scoured the archives of old newspapers and the scientific literature for word of some relevant experiment and its publication; the most recent and most thorough of these has been Dieter Zimmer, who in his 2008 book Hurricane Lolita devotes a chapter to the topic. While fundamentally agreeing with Zimmer and others that Nabokov’s anecdote is more or less apocryphal, I will offer one additional plausible source for the inspiration connecting zoo enclosures to nympholept. I will then address few key appearances of the cage-bars motif in Nabokov’s writings that were important for

[15]

him beyond the consideration of pathological solipsists.

In 2008, Leland de la Durantaye published his consideration of the primate theme in Lolita, observing along the way that Dmitri Nabokov had no knowledge of any real article behind the legend (De la Durantaye, “The Artist and the Ape. On Luxuria and Lolita.” The Nabokovian 60. Spring 2008:38-44). A valuable new batch of information was presented in Dieter Zimmer’s book Wirbelsturm Lolita - Auskünfte zu einem epochalen Roman (Reinbek: Rowohlt Verlag, 2008; chapter five provided by author without pagination), which has not been published in English. Zimmer, the unrivaled archeologist and curator of loose ends and lost threads from Nabokov’s “real” world, uses his chapter to enlarge upon the annotations to his German translation of Lolita, noting previous failures to track down any article about the Paris ape from 1939 or other years, and he adds several new observations.

Zimmer’s most productive resource is Desmond Morris’s The Biology of Art, a book on primate drawings (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962 [1961]). Morris reviews research on drawing and painting apes going back to 1913, when Russian primatologist Nadezhda Kohts began conducting drawing experiments with her chimpanzee Joni, which were collected and published as a book in 1935 (Infant Ape and Human Child [Moscow: Scientific Memoirs of the Museum Darwinianum, 1935]; now readable online in Russian, with images, at http:// www.kohts.ru/ladygina-kohts n.n./ichc/html/). Morris also presents the researches of Alexander Sokolowsky from 1928 (Erlebnisse mit wilden Tieren, Leipzig: Haberland, 1928) and by W.N. Kellogg and L.A. Kellogg (The Ape and The Child: A Comparative Study of the Environmental Influence Upon Early Behavior, [Hafner Publishing Co., New York and London, 1933]). Although it seems likely that Nabokov could have known of Joni (I have not researched her fame in pre-revolutionary Russia), and some of her drawings can even be generously interpreted as representing something bar-like,

[16]

there is a major problem: Joni was not kept in a cage. Of course, that fact does not prevent Nabokov’s imagination from making the link between cage-like scribbles and a real cage, but it is not a very satisfactory result, taken together with the fact that the book’s publication four years prior was not newsworthy in 1939 (although Nabokov could have encountered it that year, but such speculations are not especially helpful). In Sokolowsky’s 1928 book, Zimmer finds an ape named Tarzan II, residing in Hamburg, who made a single drawing in which “a reporter, with strong imagination and much good-will,” might see lines similar to the bars of a cage (Zimmer, n.p.). However, as no newspaper story about this ape or about Sokolowksy’s book has been found, Zimmer doubts the existence of such a reporter, and doubts even more strongly that Nabokov would have seen the German book itself. Sokolowsky’s book does contain one more interesting tidbit: a monkey temptingly named Hum-Hum. However, Zimmer reports that Sokolowsky says nothing of this creature except that it died young—and it was, in any case, female.

Zimmer observes that Paul Schiller’s experiments with the chimpanzee Alpha, from 1941-1951, also failed to produce bar-like drawings, although the fact of Alpha’s 200 drawings’ appearance at the onset of Nabokov’s most intense period of work on Lolita, in 1951, should not be overlooked (Paul Schiller, P. “Figural Preferences in the Drawings of a Chimpanzee.” Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology 44 (1951): 101-11). However, as Zimmer points out, this date squares poorly with Nabokov’s claim that Volshebnik itself (“The Enchanter,” written in late 1939) was allegedly the initial nympholeptic product of his ape-driven inspiration.

The top candidate for a documentary source comes from Life magazine, in a tale of discovery that ranks among Zimmer’s best. Upon viewing an item in Life mentioned in Michael Juliar’s bibliography (Nabokov’s letter to the editor concerning the butterfly in Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights,

[17]

from December [5] 1949, page 6; Bosch’s painting had been reproduced in Life three weeks earlier—on Nov. 14), Zimmer found on the opposing page of Life two letters about another image from that same previous (Nov. 14) issue: a photograph taken at the St. Louis Zoo by a shutterbug chimpanzee named Cookie. These letters observed that other photographs by chimpanzees had been published also in earlier years, including one in Life itself from Sept. 5, 1938, from the Berlin Zoo. These photographs by caged chimpanzees predictably portray the zoo visitors looking through the bars at the simian photo-journalists. Zimmer concludes that Nabokov unquestionably saw the photograph and letters in 1948, since they appeared in issues of Life he demonstrably knew. He suggests that it is not unlikely that Nabokov could have seen the Life image from 1938, an image of bars produced by an ape very close to the time when Nabokov felt his “shiver of inspiration.” According to Zimmer the inspirational link (in 1938) is not definitively proved, but he rightly claims to have shown that Nabokov’s probable familiarity with the existence of artistic apes (dating from the early- or mid-1930s) combines with the appearance of the photographed cage bars in 1948 to suggest that Nabokov had ample material from which to craft his iconic metaphor for Humbert’s psychological state.

Zimmer considers it a miracle that he came across those letters and happened to notice their contents and the connection to Nabokov’s essay. Since this work was originally done for his pre-1995 annotations to the German translation of Lolita—that is, in the very early days of the internet, when no periodicals were searchable on-line—miracles were probably necessary (although in reality, Zimmer’s tireless investigations deserve the most credit). In a genealogy of ape-art studies, T. Lenain (1995) recognized the contributions of Kohts, Schiller, and Sokolowsky, but identified Desmond Morris (1963) as the first to approach the connection between ape drawings and human art (Lenain, T. “Ape-painting and the problem of the origin of

[18]

art.” Human Evolution 10.3 [1995]:205-215). However, Morris was not the first: there is a missing link—and this link is missing in all the accounts I have found, including Morris’s own.

The missing link is a story about an artistic ape, reported anonymously in the Feb. 11, 1939 Times of London by Julian Huxley, the London Zoo’s director at the time. Huxley was a leading, even towering, figure in the new (neo-Darwinian) evolutionary synthesis; his book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis appeared in 1942, and Nabokov knew it well. Under the title “The Artistic Gorilla,” subtitled “Shadow tracings by Meng,” Huxley (under the byline “Our Special Correspondent”)described how the young gorilla Meng became fascinated by his own shadow for a brief period, during which he “proceeded to outline part of the shadow with his outstretched finger.” Huxley reports that Meng performed this act “three further times, and there was no question but that he was interested in his shadow, and was deliberately tracing its limits.” The article ponders briefly whether Meng would go on to develop greater artistic ability, and suggests that the gorilla’s actions demonstrate one of the possible ways that early humans could have discovered their own ability to create images. Huxley later published his observations in a letter to Nature (June 6,1942) and this story was covered in the Science News Letter, (Washington, DC) on Aug. 29 of that year. Nabokov did tend to look at the Times when he could in Berlin and Paris, and he might also have heard stories of Meng during his visit to London in April of 1939. (Because others have scoured French newspapers looking for relevant articles I have not duplicated this work, but Meng’s activity may have been reported there as well). Nabokov’s ape was in Paris’s Jardin des Plantes; the migration from London to Paris in the 1958 anecdote could be an artifact of memory, but is more likely pure artifice.

Huxley’s two brief articles appear to represent the first explicit scientific consideration of ape-art as a possible analog for the evolutionary emergence of human art. Especially relevant

[19]

to Nabokov’s works is the story’s emphasis on the gorilla’s fascination with the shadow’s limits. Meng, it turns out, lost interest in his shadow, and later, repeated attempts to interest him in other shadow-shapes were unsuccessful (a fact that inverts temporally Nabokov’s version, in which an ape “after months of coaxing by a scientist” made its drawing). Huxley does not speculate whether Meng knew that the shadow was in some way connected to himself; it may have been the only shadow in the enclosure at that time. Still, to an anthropomorphizing reader of Nabokov, this image meets all the necessary criteria for the idea behind Nabokov’s legend: an ape begins to create an actual drawing, and the drawing portrays the real limits of a real enclosure: in this case, the boundary of his own figure, as seen in a two-dimensional projection. Here we have in vivid form the notion (however speculative and anthropomorphized) that a creature’s first artistic instinct is to reproduce the boundaries that shape its existence. More emphatically than the Berlin chimpanzees’ photographs, this act can be read as a deliberate exploration of the enclosure that defines an individual and makes up its world. (Meng, the gorilla, almost certainly had no such notions, just as the chimps were perhaps really trying to photograph the visitors, if anything, but certainly not the cage bars; they were possibly only mimicking those visitors, who were of course photographing them, as can be seen in the Life images.The Life issues describe the conditions of the “experiments”). But Meng did deliberately trace the shadow, whereas the Berlin chimp surely snapped the bars of the cage by chance, because they were in the same field of vision as the humans).

Appending my conjecture to Zimmer’s more substantial ones, the full set of precursors now includes several drawing chimpanzees, a gorilla with a real (if fleeting) interest in visual boundaries, and a few chimpanzees that photographed the bars of their cages, all published between 1928 and 1948. There would be nothing surprising in Nabokov’s composition of his rhetorical image from these three components, as his artistic

[20]

method often created compressed allusions combining two, three, or more intertextual references. There is no reason to think that his comments for public consumption did not employ the same compositional strategy. Alexander Zholkovsky discovers this very process at work surrounding monkeys in Nabokov’s autobiography, while doubting, in the same article, the journalistic origins of Lolita’s apocryphal ape (“Poem, Problem, Prank,” The Nabokovian 47 [Fall 2001], 19-29).

I want to suggest that Nabokov’s anecdote is precisely correct about at least one thing: he became especially interested in the epistemological implications of cage bars sometime around 1939, as his anecdote suggests. At least three works from the years immediately following this time invoke imagery related to Nabokov’s recollected newspaper article: “Ultima Thule” (a monkey), “The Tragedy ofTragedy (“iron bars of determinism”), and Bend Sinister (“the prison bars of integers”). Monkeys, fateful or deterministic numbers, closed circles (“Krug,” but also as an allegory of epistemological entrapment in “Ultima Thule”) appear in teasingly philosophical contexts and lead, eventually, to ape-related imagery in Lolita. We are left with the conclusion that when Nabokov wrote about that “first little throb” that occurred in 1939 or 1940, he was writing about the impetus to conceive not only Lolita and its precursor “The Enchanter,” but much of his work during the next decade.

— Stephen Blackwell, Knoxville, Tennessee

SEBASTIAN THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

By 1938 in Paris, Vladimir Nabokov had realized that in order to maintain a readership he would have to compose his novels in English. This meant more than giving up his native tongue: Nabokov would have to abandon the Russian liter-

[21]

ary tradition of his past and assume a more culturally legible Anglophonia to give his novels their “black velvet backdrop” (Vladimir Nabokov, The Annotated Lolita, introduction and annotations by Alfred Appel, New York: Vintage, 1991,311-317, 317). However, having been raised a “perfectly normal trilingual child,” Nabokov realized that certain literary works – through translation – could maintain their relevance in multiple cultures (Vladimir Nabokov, Strong Opinions, New York: Vintage, 1973, 42-43). With his first novel in English, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, Nabokov acknowledges his transition from Russian to English-and between two worlds-by alluding to inter-culturally legible texts.

Lewis Carroll’s Alice Tales play a particularly large role as subtext in Sebastian Knight, perhaps because Nabokov was partly responsible for making them inter-culturally legible: his first published prose was a translation of Alice s Adventures in Wonderland (1923). Alice in Wonderland's plot structure, motifs, narratorial authority, cast of characters, imagery and two-world dialectic (the idea of the next world or the dream world) are mirrored in Sebastian Knight. Alice functions as a “looking-glass” that focuses a number of oppositions constructed by the test (life/hereafter, life/art, Russia/Anglophonia), and can account for several of the novel’s otherwise unexplainable images.

Characters and events from SK’s fiction seep into V.’s narrative, appearing to aid him in his biographical quest (see Susan Fromberg, "The Unwritten Chapters in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight," Modern Fiction Studies 13 (1967), 427- 442). These seepages, from art into life or life into art, open a Pandora’s box of questions about V.’s biases. Docs V. intend to gain validity as a biographer by reconstructing his journey in a way that reflects SK’s art? Yet if first hand material that V. finds on his quest can be traced back to SK’s books, perhaps V. has crafted his whole quest by rewriting them.

Alice in Wonderland first appears as a note in the “musical phrase” on SK’s bookshelf (RLSK, 39). The title is ambiguous:

[22]

Lewis Carroll never wrote a book entitled “Alice in Wonderland the specific volume V. cites; only collections of his two Alice novels –Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There – do. The scope of possible references is broadened, and one must then work from V.’s explicit Carrollian allusions inward, toward SK’s novels.

If we take V.’s biography as an objective document, one without strange intrusions from other works, then the Alice tales are mentioned only twice in the book: first on SK’s shelf, and second in Beaumont. When V. stops at the Beaumont Hotel to ask for a list of addresses in hopes of finding SK’s final lover, the hotel manager responds in the “elenctic tones of Lewis Carroll’s caterpillar” (RLSK, 121). This suggests that V. has at least read Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, since the caterpillar does not appear in Through the Looking Glass, and that V. would conceivably have the capacity to notice Carrollian references in SK’s books. If V. is weaving images taken from SK’s books into his account, he would have the literary capacity to see where SK refers to Carroll, and weave those too into his quest.

The word “elenctic” is problematic, however. Carroll never uses the word, and to this point in the narrative, V. repeatedly refers to the difficulties he faces while “tussl[ing] with a foreign idiom” (RLSK 99), which cause him to enroll in a “be-an-author” course (RLSK 32). If we accept this, how then can we account for such an arcane word choice? V. alludes to a possible answer: “I am sustained by the secret knowledge that in some unobtrusive way Sebastian’s shade is trying to be helpful” (RLSK, 99). Thus we can posit that SK assists V in writing his book (Priscilla Meyer, “Anglophonia and Optimysticism: Sebastian Knight’s Bookshelves,” Russian Literature and the West: A Tribute for David M. Bethea. Ed. Alexander Dolinin, Lazar Fleishman, Leonid Livak. Stanford, CA: Stanford Slavic Studies, 2008,212-226).

Both of these issues – V.’s text surpassing his skill; SK as –

-22-

sisting V. from another realm-pose the question of authorship, which can be addressed in four hypotheses:

1. SK is alive and has invented V., using him as a fictional construct to recount his own life.

2. V. exists, and is composing a biography of his half-brother. V. is downplaying his linguistic acumen out of his own sense of having limited ability in English.

3. V. exists, and is a talented writer. SK is his invention, which gives him the ability to discuss larger theoretical notions of biography, truth, and reality.

4. V. exists on an equal plane with SK, and writes the biography in accordance with the promptings of SK’s shade. This implies a means of contact between the realms of life and death, and a difficulty in assigning definitive authorship.

All of these hypotheses affect how the Alice tales function as subtext in the biography/novel in different ways. Hypothesis 2 contends that V is only aware of the two overt Alice citations. This would negate the possibility of SK aiding V.,which hypothesis 4 seeks to account for. The specific language of V.’s conjecture, however (SK is “[p]eering unseen over [his] shoulder”) implies that V. does not know what exactly SK is doing to help him in his quest, but only that he is helping in some way. By this logic, V. must also be unaware of how SK weaves his own subtexts – the books on his shelf, including Alice – into V.’s narrative.

That V. is unaware of SK’s contribution is substantiated by this idea of writing from over the shoulder, which proves Alice's importance to the whole text: this very idea is a veiled allusion to Through the Looking Glass. Just as Alice crosses into the Looking-Glass House, she frightens the miniature Red King by lifting him up and dropping him far from where he started. He maintains that he “shall never, never forget” the “horror of that moment,” while his Queen argues that he will, unless he “make[s] a memorandum of it” (Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-

[24]

Glass, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009,133). When the king begins to write, Alice takes “hold of the end of the pencil, which came some way over his shoulder, and began writing for him” (Carroll, 133). The King is subsequently shocked when he realizes he’s been writing “all manner[s] of things that [he hadn’t] intend[ed]” (Carroll, 133). This becomes a model for the V./SK authorial relationship: SK “takes hold” of V.’s pencil, and makes him write “things he doesn’t intend.” Even though V. doesn’t intend the reference, it is nonetheless present, suggesting that unbeknownst to V., Alice is SK’s subtext to his quest.

At V. ’s meeting with SK’s friend (the “informant”) from his Trinity College years, V. notices “Sebastian’s spirit...hovering about us with the flicker of the fire reflected in the brass knobs of the hearth” (RLSK, 43-44). Then, the informant is suddenly “stroking] a soft blue cat with celadon eyes which had appeared from nowhere” (RLSK, 45). Just as the informant is going to tell V. about SK’s final Cambridge year, the cat stops him from speaking: “I don’t know what’s the matter with this cat, she does not seem to know milk all of a sudden” (RLSK, 48). This cat is distinctly Carrollian and must be compared with the Cheshire Cat (David S. Rutledge, Nabokov's Permanent Mystery: The Expression of Metaphysics in His Work. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011, 180).

There is no such thing as a blue cat; the description “blue” refers to a bluish-gray fur that is found in only two species: the Russian Blue and the British Blue. The first is native to Russia, and specifically, legend has it, to the Archangel Isles (The Russian Blue, http://www.russianblue.info/russian_blue_faqs.htm, December 12th, 2010). The species was officially recognized as a breed in 1875 when it was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in London, after Russian sailors brought the species to England in the 1860s (The Cat Fanciers Association, Inc. http://www.cfa.org/chent/breedRussianBlue.aspx, December 12th, 2010). This trajectory mirrors SK (and VN) leaving Russian for England. The British Blue is a descendent of cats brought by

[25]

the Romans to England that subsequently mated with native breeds (The Cat Fanciers Association, Inc. http://www.cfa.org/ Client/articlebhorthari.aspx, December 12th, 2010). The breed has the same fur color as a Russian Blue, but is much stockier, lending the cats large cheeks that make them appear to grin. Indeed John Tenniel, Lewis Carroll’s original illustrator, modeled the Cheshire Cat on a British Blue in 1865, even before it had been officially named (Pet MD, http://www.petmd.com/cat/breed/c_ct_british_shorthair, December 12th, 2010).

Thus, when V. says that the cat was simply “blue,” we’re left with a rich ambiguity. Because of the Blue’s emigration from Russia to England, we can consider SK’s presence to be manifested in this cat. Further, the cat’s bizarre actions (i.e. appearing from nowhere, and not knowing milk in a Carrollian reversal of logic) relate it to Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, and by extension, the British Blue. The cat’s presence, then, speaks directly to SK’s (and VN’s) transition from Russia to Anglophonia. Moreover, V.’s noticing the cat, dictated by the cat being the manifestation of SK’s spirit, prompts V. to unknowingly craft the Alice tale as subtext into his narrative.

This idea that SK inserts Carrollian characters into V. ’s quest in order to help him is further corroborated in the scene in SK’s study. We’ve seen Alice in Wonderland on the “one shelf [that] was a little neater than the rest,” but other parts of SK’s study function in a similarly Carrollian way (RLSK, 39). The studio is filled with the stuff of SK’s life – his letters, his manuscripts, his novels – leading one to suspect that a “transparent Sebastian” could be present (RLSK, 37). Looking around, V notices that “all the things in th[e] bedroom seemed to have just jumped back in the nick of time as if caught unawares, and now were gradually returning my gaze, trying to see whether I had noticed their guilty start” (RLSK 35). This strange liveliness of SK’s objects mirrors the fantastical shop scene in Through the Looking Glass: when Alice peers around the shop, she notices that “whenever she looked hard at any shelf.. .that particular

[26]

shelf was always quite empty, though the others round it were crowded as full as they could hold” (Carroll, 149).

SK’s study is his realm; it is where he “build[s] [his] world[s],” and reigns supreme (RLSK 88). If we remain faithful to hypothesis 4, his spirit could maintain this kind of control after death, especially over his artistic workplace. So the very way that V. is made to observe SK’s study in response to a Carrollian phenomenon – which ends in finding that relevant shelf – can be viewed as SK’s spirit’s doing. SK enters V.’s world through his own novels and the books he loves, to inform the direction that V. will take.

There is one instance in the narrative that combines these two kinds of responsibility for the subtext. In The Back of the Moon, one of the three short stories in The Funny Mountain, V. describes the character Mr. Siller as “perhaps the most alive of Sebastian’s creatures,” who seems to have “burst into real physical existence” (RLSK, 102). On the train back from Blauberg to Paris, at a loss for information that could help him on his quest, V. “[a]ll of a sudden notice[s] that the passenger opposite [is] beaming at [him]” (RLSK, 123). This is Silbermann, who is described as having the same features as Mr. Siller: “big shiny nose,” an Adam’s apple that “roll[s] up and down” etc. (RLSK 124). Mr. Siller has now burst into life and will help V. get the women’s addresses he needs by talking to the “hotel-gentlemans” he has in the palm of his hand (RLSK, 128).

Silbermann follows Carrollian reversed logic. Having given him the addresses and a silver notebook, Silbermann tells V. that he owes him money “dat’s right, [eighteen and two make twenty. ...Yes twenty. Dat’s yours” (RLSK 131). Instead of V. paying for these services, he gets paid by the man who provides them; left has become right, and V. is helped by someone from the other side of the looking glass.

This reversal of logic, paired with his role as magical helper, links Silbermann to the White Knight, Alice’s most sincere and joyous helper. The White Knight appears to Alice

[27]

when she is at a loss for her next move: she is about to become a prisoner of the Red Knight, just as V. has no more “data” to work with when Silbermann appears to him (RLSK 119). The White Knight battles the Red Knight, eventually winning out, and he becomes Alice’s guide through the woods. The White Knight ascribes to a form of backwards logic analogous to Silbermann’s: he carries a “little deal box fastened cross his shoulders, upside-down, and with the lid hanging open” (Carroll, 211). He carries it this way “so that the rain ca’n’t get in” (Carroll, 211). Alice notes that the things he puts in it will “get out,” and when asked if he realizes this, the Knight responds, “I didn’t know it” (Carroll, 211).

Even if we accept this as another intrusion of SK’s works (The Back of the Moon) into V.’s quest, one must still account for the scene’s Carrollian intonations. All we are told of The Back of the Moon is that it involves Mr. Siller waiting “for a train [and] helping] three miserable travellers in three different ways” (RLSK 102), so that there is no way to determine if Carroll’s tales work as a subtext in SK’s story; in this context, we can only know that SK must have placed them in V. ’s realm.

These constitute most of the indisputable references to Carroll in the book. With these points of connection in mind, we can examine the novels’ shared thematic concerns. Both Carroll tales posit the existence of two worlds: the “real” and the “dream.” Sebastian Knight is overtly concerned with the process of biography, but the attempt to understand the other side of the “question”– of the “hereafter” (RLSK 175, 202) – is perhaps even more important: first for SK in The Doubtful Asphodel, then with V. trying to overtake SK at the brink of death.

How then does one cross between these two worlds? In both Through the Looking Glass and Sebastian Knight, mist functions as a barrier between them. The Looking-Glass, through which Alice can always see her other realm, finally allows her through when she notices that it “wax beginning to melt away, just like a bright silver mist” (Carroll, 128). Similarly in Se-

[28]

bastian Knight, communication with any other realm (life or art) comes complete with mist. Further, this holds true in both SK’s novels and V.’s quest. The Carrollian scenes are therefore often associated with mist.

Mist first occurs when V. quotes Lost Property, SK’s “most autobiographical work” (RLSK 4). When SK’s autobiographical character is at Roquebrune, the same place that SK’s mother died, he “work[s him]self into such a state that for a moment the pink and green seem to shimmer and float as if seen through a veil of mist” (RLSK, 17). He sees “his mother, a dim slight figure in a large hat” in this mist as well, and she walks “slowly up the steps which seemed to dissolved into water” (RLSK, 17-18). Here, SK is connected, through his quest for his dead mother, to the hereafter. And right before V. meets the other- worldly Silbermann, V. notes the “pale mist; like the valley I was contemplating” (RLSK, 123).

V. describes a similar experience when he meets with the informant, another scene filled with Wonderland imagery. Just as V. is listening to the informant’s last words, a “sudden voice in the mist” says, “[w]ho is speaking of Sebastian Knight?” (RLSK, 49). The presence of “Sebastian’s spirit” is noted immediately thereafter (RLSK, 43). Like the blue cat, which is an emanation from the realm of art, SK has again entered V.’s world from the hereafter by means of an implicit Carrollian reference.

Both of these references have to do with the traversing of a gap (life/art, life/death) in the presence of mist. V. describes the “opposite bank” of the “abyss [...] between expression and thought” as “misty” (RLSK, 82). SK’s novel acknowledges that man can “only know this side of the quest” (RLSK 175). These surges from the unattainable realms into V.’s quest are shrouded in mist, “a diffuse cloud of fine water droplets that... limit visibility” (“Mist.” Oxford English Dictionary. Second Edition. 2010). Mist becomes a poetic barrier: connection between any two realms becomes difficult, due to the reflections

[29]

and refraction of light between each drop of water. The mist initially belongs to SK, who has borrowed it from Carroll. It then makes its way into V. ’s narrative, via SK’s spirit presence, but we cannot be sure. This then holds true for all of the Alice references in the narrative: we may trace them to a certain extent, but counter-arguments as to varying degrees of authorial agency can be easily made, and become further complicated when V. states “I am Sebastian, or Sebastian is I, or perhaps we both are someone whom neither of us knows” (RLSK, 203).

The Alice subtext is largely responsible for this narratorial ambiguity. As Fromberg points out, “the last speech [in Sebastian Knight] is a deliberate and conscious echo of the final speech of Alice in Wonderland" (Fromberg, 439). After Alice wakes up, she recounts her dream to her sister, who, after Alice leaves shuts her eyes and begins to dream Alice’s dream herself. Thus Alice’s sister becomes part of her sister’s illusion, her “art,” as if she were participating in a sort of general dream that anyone could tap into, given the tools.

V. has spent his whole quest being told about SK’s life, much as Alice tells her sister about her dream. By the end of his quest, V. has learned that “the soul is but a manner of being ... any soul may be yours if you find and follow its undulations” (RLSK 202). Thus with the information he has attained (albeit with the help of SK), V. can tap into another’s soul, as Alice’s sister does when she begins to have Alice’s dream.

But there remains one major difference: Alice’s sister has not become Alice, whereas V. claims he “perhaps” has become Sebastian (RLSK, 203). There is a permanent ambiguity of internal authorship that cannot be solved. V. relies on SK for his material and guidance, and SK relies on V. for the physicality of writing. Thus, the authorship remains in flux.

This flux is yet another implicit reference to Carroll: the problem of the Red King in Through the Looking Glass. While with Tweedledee and Tweedledum, Alice comes across the

[30]

Red King asleep, dreaming. Thus far, we’ve had to consider Alice as the “author” of her dream, but Tweedledum insists that Alice is “only one of the things in his dream. You know very well you’re not real” (Carroll, 168). Alice responds, “I am real!” and begins to cry (Carroll, 168). Then who is part of whose dream? The narrative stance points toward the King as part of Alice’s dream, just as, simply read, the narrative stance in Sebastian Knight points to SK being part of V.’s “dream.” But the insolubility of this conundrum mirrors the possibility of V. as part of SK’s dream.

But why should SK choose to communicate with V. through subtexts, and specifically through Carroll’s tales? Thematically, Carroll’s stories are concerned with sets of realities, just as SK’s novels search for the hereafter. With the authorship in constant and meaningful flux, we must take a step back to assess this “someone whom neither [V. or SK] knows,” a possible writer of the narrative (RLSK 203).

Logically, this has to be Nabokov. Whereas SK has no particular reason to inform V. through subtext save a beautiful imitation of art in life, Nabokov does. For Nabokov, this novel represented the jump across the abyss from Russian to Anglophonia. That he imbues his first English novel with unusually overt allusions and subtexts, as compared to his other novels, highlights the importance and discomfort of his transition.

Since VN and SK are so similar (both bom in 1899, both attend Trinity College, Cambridge, both fathers participate in a duel), literary works important to SK must also be important to VN. Nabokov’s translation of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland from English to Russian as Ania v Strane Chudes reverses the national direction of his novel. Carroll himself was a kindred spirit with his simultaneously scientific and artistic goals. That Carroll’s work maintained cultural significance in Russian and English – a kind of bridge in itself – mirrors VN’s transition. Carroll’s work acts as a thematic mirror for the main concerns of VN’s novel: the connection between two different worlds and

[31]

the concept of a hereafter or aftertime.

In her dream, Alice manages to cross through the mist into her other world, like V. who makes contact with SK (and Alice) in the mist. The bridging of these two worlds is the goal of V.’s narrative. VN, faced with the pain of losing his idiom, referred to an inter-culturally legible text to weave his “black velvet backdrop,” bridge his cultural abyss, and acknowledge his loss.

—Zachary Fischman, Middletown, CT