Download PDF of Number 63 (Fall 2009) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 63 Fall 2009

______________________________________

CONTENTS

News 3

by Stephen Jan Parker

From Dmitri Nabokov 5

Regarding The Original of Laura

In Memory of Simon Karlinsky 7

by Brian Boyd

In Memory of Alfred Appel, Jr. 15

by Brian Boyd

Notes and Brief Commentaries 23

by Priscilla Meyer

“Nabokov’s Lolita and Frost’s ‘Design’: 23

‘A Witches’ Broth’ of Coincidence”

– Misty Jameson

“Castor and Pollux in Pale Fire” 28

– Jansy Berndt de Souza Mellow

“Baudelaire, Melmouth and Laughter” 34

– David Rutledge

‘“Mountain, not Fountain’: Pale Fire’s 39

Saving Grace”

– Gerard de Vries

“Beheading First: On Nabokov’s Translation 52

of Lewis Carroll”

– Victor Fet

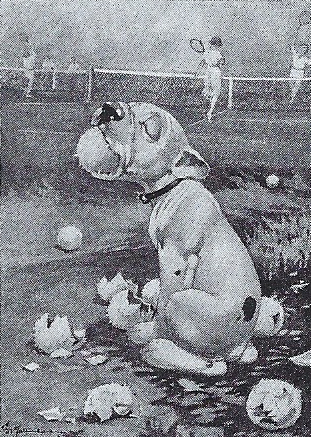

“On the Original of Cheepy: Nabokov 63

and Popular Culture Fads

– Brian Boyd

“Lehmann’s Disease: A Comment on 72

Nabokov’s The Real Life of Sebastian Knight

Savely Senderovich and Yelena Shvarts

2008 Nabokov Bibliography 81

by Stephen Jan Parker and

Kelly Knickmeier Cummings

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 63, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

The Original of Laura appears in mid-November in the USA and then simultaneously, or most rapidly, translations appear around the world. Tremendous attention is given and readers’ responses vary greatly. The question arising over and over again is “upon what basis was this work published?” Some conclude “It should have been published.” Other conclude: “It should not have been published.” The final answer to this nagging question is given most clearly and concisely by Dmitri Nabokov in this issue.

*****

Odds & Ends

1. Dr. Kurt Johnson (co-author of Nabokov's Blues and articles regarding Nabokov’s science) has donated his highly extensive archives on Nabokov and Nabokov’s science to the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera at the University of Florida, Gainesville. Therefore, he has now established the primary site for research and studies concerning Nabokov and lepidoptera.

2. Few books have received as much attention regarding how they can be taught and read as has Lolita. Following Approaches to Teaching Nabokov's “Lolita, ” edited by Zoran Kuzmanovich and Galya Diment (MLA, 2008), which offers a broad array of perspectives, we now have Julian Connolly’s A Reader ’s Guide to Nabokov’s “Lolita” (Academic Studies Press, 2009). Connolly’s most perceptive work takes a reader/student through the creation and precursors of Lolita, ways to approach and analyze

[4]

the work giving special care to detail, and helpfully looks over the critical and cultural responses which have been engendered by this national and international classic.

*****

As usual now for several decades, I wish to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential on-going assistance in the production of this publication.

[5]

From Dmitri Nabokov

Regarding The Original of Laura

Well, after a period of pensive procrastination, sporadic at first, then increasingly focused, Laura is finally emerging from the dark of a bank vault into broad daylight.

Meanwhile, I have learned that I am slippery, that Laura is but a Nabokovian mystification, that I appealed to my friend Martin Amis to complete the unfinished novel, and that I do not exist, but am, together with my extravagant CV, a pure invention on the part of Vladimir Nabokov, who has been living on to a fantastic age in an unattainable hiding place.

Yet here I am, and there is Laura, complete only in part, a congeries of fascinating fragments exactly as my father wrote it, except for the correction of a very few, very obvious lacunes. The idea was to edit as little as possible, in order to show the Master at work at his lutrain (bookstand), and then in his hospital bed, filling his index cards with the minute script of his No.2 pencils, reaching the 138th card just before his death. Had I myself not fallen ill at the wrong moment, some further small corrections would have been made — for example, at the end, the orphan “navel” might be preceded by “my” or made plural, but I don’t think, as has been suggested, that Nabokov had intended to say “contemplating my navel”. Of the typical repetitious questions — “if he wanted Laura to be burnt, why didn’t he do it himself?”; “why did I contravene his command that it be destroyed?”; or perhaps, a question no one seems to have asked: “does the list of words on the very last card refer to self-immolation on Wild’s part, or, hypothetically at least, the immolation of the manuscript?” — all those regarding VN’s intentions or my actions can be answered in the twinkling of an eye: when asked what books he was reading or would keep, he replied: “Charles Singleton’s translation of Dante’s Inferno; The Butterflies of

[6]

North America by William H. Howe; The Original of Laura, the not-quite-finished-manuscript of a novel I had begun writing before my illness and which was completed in my mind” — hardly words typical of an author who wants that novel destroyed.

Rare is the verbiage that prompts a special reaction. One such example is the title previously perpetrated by a particularly pernicious member of the pansy patrol, and now exhumed by homo hunters among Nabokov’s relatives and in his works -— “Queer, Queer Vladimir”. My reaction, were it legal, would be a swift kick in the teeth.

© 2009 Dmitri Nabokov

[7]

In Memory of Simon Karlinsky

by Brian Boyd

Simon (Semyon Arkadievich) Karlinsky, a leading scholar of Nabokov and of Russian literature and culture, and from the late 1960s a friend of the Nabokovs, died on July 5, 2009, aged 84.

He was bom on September 22,1924, in Harbin, Manchuria, then the largest Russian émigré enclave for those who fled Russia to the East. At eleven he first read about Vladimir Sirin and at twelve began reading him. He arrived in the United States in 1938, completing secondary school in Los Angeles. From December 1943 to March 1946 he served in the US Army, and until 1957 as translator and interpreter in Europe for the Department of State (1945-50) and the US Control Council for Germany (1946-48), and as the Liaison Officer for the US Command in Berlin (1952-57). During these years he also studied musical composition at the École Normale de Musique in Paris and at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik.

Returning to the US, Karlinsky called on Nabokov’s “great friend” (VN to SK, 11 May 1971) Gleb Petrovich Struve (1898-1985), the first academic historian and critic of the Russian literary emigration, who told him he belonged in Slavic literature. After a BA at the University of California, Berkeley, and an MA at Harvard with Vsevolod Setchkarev, Karlinsky returned to Berkeley to write a dissertation on Marina Tsvetaeva under Struve. He joined the faculty there in 1961, completing his PhD in 1964. Struve, like Nabokov, was the son of a leading pre-revolutionary Russian liberal and Constitutional Democrat, and for Karlinsky writing and teaching about the pre-revolutionary liberal tradition and the Russian emigration would remain powerful motives in a milieu where Russian and émigré culture were so little known. Indeed in 1963 when he submitted his first academic article on Nabokov, on “Dar as a Work of Literary Criticism,” the editors of Slavic and East European Journal

[8]

were uncertain Dar was important enough to discuss, and had to be reassured by Struve that it was. Struve encouraged Karlinsky to send the article to Nabokov, who welcomed the first scholarly treatment of his major Russian work: “it was a great pleasure for him to find that his book had been read by you (and written about) with such admirable care, insight, and attention to the details which are dear to their creator” (VéN to SK, 18 November 1963).

Among the first generation of academic Nabokov critics to emerge in the 1960s—Andrew Field, Carl Proffer, Alfred Appel, Jr., Robert Alter—Karlinsky was easily the greatest Slavist and, along with his Berkeley colleague Alter, the most elegant stylist. As a Slavist he wrote especially about eighteenth-century drama, Gogol, Chekhov, Chaikovsky, Stravinsky, Diaghilev, Tsvetaeva, Nabokov, Poplavsky, and many others, both for academic audiences and in serious periodicals. From 1976 he also began to publish on gay matters, becoming one of the first academics to argue for gay liberation and gay studies, focusing especially on gay aspects of Russian culture, including his 1976 book The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolay Gogol.

In January 1969 Karlinsky nominated Nabokov for the Nobel Prize in Literature. In September of that year, in Montreux, he met Vladimir and Vera Nabokov for the first time, passing the playful legpull tests Nabokov posed for him and being rewarded with the manuscript ofNabokov’s “Notes to Add" (see Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, 571-72). Early in 1970, having just reviewed recent volumes of Russian verse translation in a similar vein, he welcomed Nabokov’s reproof to Robert Lowell for his “adaptations” of Osip Mandelshtam (“On Adaptation”).

Karlinsky contributed articles on “Nabokov and Chekhov: The Lesser Russian Tradition” and on Nabokov’s translation of Alice in Wonderland to the special issue of Triquarterly edited as a Festschrift in Nabokov’s honor by Alfred Appel, Jr. He compared the puzzled receptions that had often greeted Chekhov and Nabokov in Russian literary circles, the sense that they

[9]

weren’t serious enough, that they chose art over ideology, that their objectivity and precision were somehow alien to Russian soulfulness. Nabokov responded that he “greatly appreciate[d] being with A.P. in the same boat—on a Russian lake, at sunset, he fishing, I watching the hawkmoths above the water. Mr. Karlinsky has put his finger on a mysterious sensory cell. He is right, I do love Chekov dearly” (SO 286).

In an April 1971 article in the New York Times Book Review Karlinsky pointed to the Russian subtexts in Nabokov, especially in The Gift and Ada, and the Russian contexts unknown to most American readers, like Pushkin, Lermontov, Bely, Sologub, and Remizov (the editors altered his title “Nabokov’s Russian Dimensions” to “Nabokov’s Russian Games,” under which it was also reprinted in Phyllis Roth, ed., Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov, 1983). Nabokov wrote to Karlinsky that he read “your elegant and important article with great interest” (VN to SK, 15 April 1971)—further evidence that he was not, as Alexander Dolinin suggested in 2005, eager by this point in his life to minimize his Russian roots.

In 1971 Karlinsky volunteered to translate “Krasavitsa” (“A Russian Beauty”). After approving and correcting the translation, Nabokov asked how much Karlinsky wanted for his work. Karlinsky thought it odd to charge for a labor of love, but suggested whatever was the going rate. “Or perhaps you might let me have a translation of a Khodasevich poem or two for the Tri-Quarterly issue on émigré literature I’m preparing” (SK to VN, 12 July 1971). Nabokov sent $60, which Karlinsky thought so risibly small he framed the check—and when Alfred Appel, Jr., reported this back to Nabokov, he received another $40. Nabokov also contributed translations of three poems and his essay on Khodasevich to Karlinsky and Appel’s edition of the 1973 Russian emigre literature special issue of Triquarterly, also published in book form as The Bitter Air of Exile: Russian Writers in the West, 1922-1972.

In late 1972 Karlinsky urged his friend Edmund White

[10]

to solicit Nabokov for a new essay for the special Nabokov issue of the inaugural issue of Saturday Review of the Arts that he was editing. Nabokov agreed to the request, writing “On Inspiration.” Soon afterwards he read and liked White’s first novel, Forgetting Elena, and welcomed Karlinsky’s positive review of the novel in 1974. His own public endorsement of White’s book in 1975 helped boost the career of the young novelist—by then working on The Joy of Gay Sex.

In September 1973, on his way back from his first trip to the Soviet Union, Karlinsky again visited Montreux. Nabokov, still composing Look at the Harlequins! asked Karlinsky for his first impression of Petersburg (“Loud women’s voices, swearing obscenely,” he answered) and incorporated it into the novel. He also could not stop discussing his distress at the manuscript of Andrew Field’s biography. Karlinsky offered to act as an intermediary between Field and Nabokov, now communicating only through lawyers. When he wrote to Field he was told that he was “a schoolteacher to the marrow of your bones” and, as Karlinsky reported to the Nabokovs, should not interfere in this tussle between two giants (SK to VN and VeN, 10 October 1973).

After this visit, Nabokov asked Frank Taylor of McGraw-Hill: “Tell me, is Simon Karlinsky homosexual? I have a feeling he is. But it doesn’t matter, I like him anyway.” Hearing this from Frank Taylor, Simon was surprised and impressed that Nabokov had guessed, since he had learned to be very discreet with those who he was unsure could handle the information. He was also surprised to hear, later, that some thought Nabokov homophobic.

Véra Nabokov wrote to Karlinsky that his 1973 edition of Chekhov’s letters was “absolutely first class” (22 February 1974). This judgement would lead to his most important Nabokov project, his edition of The Nabokov-Wilson Letters. After Edmund Wilson died in 1972, his widow Elena began assembling an edition of Wilson’s correspondence, and asked

[11]

Nabokov whether he would want any letters to him included. In May 1974 Nabokov replied he would be delighted, but that he thought it would be still better to publish both sides of the correspondence.

After Elena Wilson had laid out what would become Edmund Wilson’s Letters on Literature and Politics 1912-1972 (1977), she returned to the Nabokov-Wilson correspondence. Realizing that she did not have the specialized knowledge of Russian prosody needed to annotate their correspondence, she considered Gleb Struve, Harry Levin’s wife Elena, and Karlinsky as possible editors. Nabokov did not think Elena Levin qualified; Véra warned about Struve’s being difficult and recommended Karlinsky as younger and “very knowledgeable” (VéN to Elena Wilson, 21 January 1976). In February 1976 Elena Wilson therefore invited Karlinsky to edit the volume. Nabokov was having difficulty meeting the schedule of his second multi-book agreement with McGraw-Hill, signed in April 1974, and hoped the correspondence with Wilson could count as one of the required books, if it could be published by early 1977: “Is there any chance of your re-arranging your schedule? V. V. would be very much disappointed should it prove impossible for you to do the editing. Please, try!” (VéN to SK, 18 March 1976). Such a rapid schedule for such a large correspondence, needing considerable annotation, proved impractical. The book would eventually be published in 1979, and not by McGraw-Hill but by Harper and Row.

Late in 1976 Karlinsky sent Nabokov his The Sexual Labyrinth of Nikolay Gogol. Still groggy after the illness that had hospitalized him over the summer, Nabokov replied at the beginning of January 1977: “I think you over-symbolize the sexual meaning of certain marginal objects, and I am sure you overpraise certain writers: how can one rank the great Griboedov with such a mediocrity as Hmeltnitsky? Otherwise your book is a first-rate achievement” (VN to SK, 3 January 1977). That was to be the last communication between author and critic.

[12]

At Berkeley Karlinsky was supervising, with Robert Alter, the dissertation of a future leader of the next generation of Nabokov academics, Ellen Pifer, and editing the Nabokov-Wilson correspondence. Conscious of “a new generation of American intellectuals who view Lenin and the Bolsheviks as the great libertarians and who know nothing of the Chemyshevskyan tradition that preceded Lenin or of the importance of the entire Silver Age” (SK to VeN, 12 July 1976)—a generation whose views thus resembled those Wilson formed in the 1930s, but, Karlinsky thought, were more amenable to factual correction—he wrote his long introduction to The Nabokov- Wilson Letters with the need for historical contextualization foremost in mind.

In May 1979, soon after defending my PhD thesis at the University of Toronto, I saw the Nabokov-Wilson Letters on sale in New York, noted that Nabokov’s side of the correspondence was at Yale’s Beinecke Library, and promptly headed there. I discovered 23 Nabokov letters omitted from the book, and errors of dating or identification. I wrote to Karlinsky praising his edition as the first piece of real scholarship on Nabokov—the first to provide rich and mostly reliable details of much of Nabokov’s life in the English-language phase of his career—but I also pointed out the errors and omissions. I added that I would be in San Francisco in late June on my way back to New Zealand. Three days before I was due to leave Toronto, I received a letter from Vera Nabokov, who had just read my dissertation and invited me to Montreux. I promptly rerouted myself across Europe rather than North America, and was chagrined to hear from Simon later that he had still been awaiting my arrival during the days I had expected to be in San Francisco.

Véra Nabokov invited Karlinsky to introduce the 1981Lectures in Russian Literature, but when she read his text, she saw his contextualizing of the well-known figures in the volume, from Gogol to Gorki, as a criticism of the emphases in Nabokov’s teaching. She wrote to him that his approach was “in direct opposition to VN’s.... In your introduction you are

[13]

concerned with a history of Russian letters while VN’s concern is exclusively with a few works he considered the highest achievements of Russian [prose] literature in the 19th century.” (VéN to SK, 3 June 1981). Fredson Bowers, the editor of the lectures, a specialist of editing Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, was asked to write an introduction in his stead. Karlinsky was hurt at the rejection but soon recovered.

While working on my Nabokov biography in Montreux in 1982—and in the process finding two more batches of letters for a revised Nabokov-Wilson volume—I met Simon for the first time at a conference on Russian émigré literature in nearby Lausanne. Short, ideally bald, with a white beard and moustache outlining his face, he spoke in accented, clipped, rapid English, his delivery urgent and serious, even when, as often, the smile on his lips gave the lie to his earnest tone. With Robert Hughes and John Malmstad, also at the conference, he visited Véra in Montreux, I think for the last time.

I interviewed Simon for the biography a number of times, in Lausanne, in the home in Kensington, California, he shared with his partner Peter Carleton (whom he married in 2008), and in Jack London Square. On completing the biography I sent him and other leading Nabokov scholars the manuscript. After reading the first six chapters all day Simon wrote: “At some point during the day I felt a sense of relief which I couldn’t quite identify. It has to do, I think, with a sense of guilt somewhere in the back of my mind about not having done anything big about Nabokov during those years I’ve spent convincing people of the uniqueness of Tsvetaeva (people who can’t read her) or trying to bring Chekhov closer to Western readers or telling them what Gogol was really all about. Nabokov, with whose writings I fell in love when I was 12 and he was still Sirin, does not lack interpretations. But now you’ve done what I had half-consciously felt was my duty to do.. . . Hence, this relief—I am no longer obligated and Sirin-Nabokov is in very good hands” (SK to BB, 28 August 1987). His feedback was superb, especially his

[14]

insistent exhortations to explain Russian references in full to an audience that knew so little about Nabokov’s background.

In 1989 I happened to change planes in San Francisco, and called Simon from the airport. He told me excitedly about the Tsvetaeva conference in Moscow from which he had just returned, and exhorted me: “You must go back to Russia” (which I had visited, on Nabokov’s trail, in 1982). “This time, they’ll show you everything.” I took his advice next year, and found material now incorporated into the major translations (French, German, Russian) of the biography, but in English, fittingly, published only in a Festschrift, For SK: In Celebration of the Life and Career of Simon Karlinsky, ed. Michael S. Flier and Robert P. Hughes (Berkeley Slavic Specialists, 1994), on the occasion of his retirement from Berkeley.

Karlinsky had hoped to incorporate into the paperback the Nabokov and Wilson letters found after the first hardback edition, but the publisher did not want to defer the announced paperback date and incorporated only minor corrections. He then continued to try to find a publisher for a thoroughly revised edition of the letters. Even after the success of the 1998 play, Dear, Bunny, Dear Volodya, adapted movingly from the correspondence by Terry Quinn (with Dmitri Nabokov sometimes playing his father), it was not until 2001 that the University of California Press published Karlinsky’s revised and expanded edition, now itself called Dear Bunny, Dear Volodya.

The opening of the Festschrift for his retirement provides a fitting close: “Simon Karlinsky is without question one of the most influential cultural critics to have emerged from the emigration.”

Unpublished material by Vladimir and VeraNabokov quoted and © by permission of Dmitri Nabokov and the Nabokov Estate.

[15]

In Memory of Alfred Appel, Jr.

by Brian Boyd

Alfred Appel, Jr., best known to Nabokovians as editor and annotator of The Annotated Lolita and as Nabokov’s good friend in the late 1960s and early 1970s, died of heart failure on May 2, 2009, aged 75.

Born on January 31,1934, in New York, Alfred grew up in Great Neck, N. Y., where he edited the Great Neck High School newspaper and had lead roles in numerous school shows. He attended Cornell from 1951. In his sophomore year, he read The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and realized, unlike most Cornell students, the astonishing writer they had in their midst. In the 1953-1954 school year he took Nabokov’s Literature 312 course, Masterpieces of European Fiction, which he and his future wife Nina, who starred in the course a year later, thought their “most inspiring and meaningful academic—or, rather, artistic—experience at Cornell” (AA to VN, 25 September 1958). In the winter of 1955 Alfred was discharged from Cornell “because of my anemic ‘points-toward-graduation’ count,” and served two years in the US Army. In 1957, on his return from the Army and Europe, he married Nina Schick, and in 1958, now a student at Columbia, wrote to his former Cornell teacher congratulating him on Lolita'?, success in America. He not only related the Stockade Clyde story he would later make famous in the introduction to the Annotated Lolita but wrote also that “ ‘312’ was my first vital encounter with literature: your lectures on Proust and Joyce captured my imagination as no course has since, and, frankly, influenced me in pursuing my present studies in English.” In 1959 he completed a BA in Literature and Fine Arts at Columbia, and continued there to a PhD in English on Eudora Welty. As a young teacher at Columbia he shared an office with Robert Alter, later another leading light in the first generation of Nabokov scholars.

By 1965 Alfred was at Stanford, teaching Lolita and Pale

[16]

Fire in his 180-strong American Novel lecture course. His seminar course, Studies in the Grotesque, helped inspire Page Stegner in his PhD dissertation and in what would become the first academic book on Nabokov, Escape into Aesthetics: The Art of Vladimir Nabokov (1966). Preparing for a special Nabokov issue of Wisconsin Studies in Contemporary Literature, the first multi-author volume on the writer, Alfred wrote to Nabokov asking if he could come to interview him. He and Nina stayed four days in Montreux with the Nabokovs, September 25 to 29, 1966 (Strong Opinions, interview 6) and established what would become a warm friendship. Nabokov’s reputation in the 1960s often made others tongue-tied when they at last were allowed to see him. Nothing daunted Alfred or his sense of humor.

Later that year Alfred was working on a volume on Nabokov for New Directions’ Makers of Modern Literature series, to include a “brief biographical chapter” (A A to VNs, 5 December 1966). On 14 and 21 January 1967, for the launch of Speak, Memory, the New Republic published his “Nabokov’s Puppet Show,” their longest literary review since Edmund Wilson’s two-part review of Finnegans Wake in 1939, and the first detailed explication of Nabokov’s self-conscious strategies and their implications, like “the transcendence of solipsism.” Vera Nabokov wrote to Alfred: “Your essay ... is so brilliant and profound that I cannot resist telling you of the pleasure it gave my husband. If he ever broke his rule not to thank critics, this would have been the occasion. (This is cheating a little, as you may notice.)” (VéN to AA, 24 January 1967).

Early in February Alfred proposed an annotated Lolita. Vera reported that VN found the idea “extremely attractive and interesting, and says you arc quite right—the comments should be strictly factual and utilitarian” (VéN to AA, 20 February 1967). From March to December 1967 Alfred sent to Montreux draft annotations to Lolita, which Nabokov would return with detailed emendations and explanations. The Appels visited Montreux for another “marvelous time” in January 1968. The

[17]

next month, Alfred proposed an annotated Pale Fire; not until a reminder a year later did Nabokov reply: “Pale Fire may be commented [sic] in a separate pamphlet . . . but not as an annotated edition since it already is (a parody of) an annotated edition. Your sunlight would dilute my moonshine” (VN to AA, 30 May 1969). In July 1968 Prentice-Hall asked Appel to edit a Nabokov volume in their highly successful Twentieth-Century Views series. In October, by now teaching at Northwestern University, Alfred mentioned to Nabokov the Triquarterly Festschrift planned for the fall of 1969, and asked him for some fresh Nabokoviana for the volume but received the reply that “a festschriftee should not contribute his own works” (VéN to AA, quoting VN, 20 October 1968)

One day during the Appels’ January 1968 visit Nabokov had told them he had just completed Part 1 Chapter 32, the blue pool scene, of Ada. On 4 May 1969, the eve of the novel’s publication, Alfred’s front-page New York Times Book Review essay appeared, hailing Ada as “A supremely original work of the imagination. . . . further evidence that [Nabokov] is a peer of Kafka, Proust, and Joyce. ... a love story, an erotic masterpiece, a philosophical investigation into the nature of time.” Two days earlier Nabokov, after reading the advance of the review, had telegraphed Alfred: “ADA JOINS ME IN SALUTING AN ADMIRABLE READER. VAN VEEN.” By October 1969 Alfred, still working on his Nabokov volume for New Directions, although now thinking it should move to Nabokov’s new publisher, had also discussed with McGraw- Hill the possibility of an Annotated Ada.

1970 saw the publication of both the Triquarterly Festschrift (co-edited with Charles Newman, and also appearing in hardback as Nabokov: Criticism, reminiscences, translations and tributes) and the Annotated Lolita, which Nabokov welcomed generously: “How delighted I am that you undertook this task! ” (VN to AA, 9 June 1970). From August 28 to September 2 Alfred and Nina Appel stayed with the Nabokovs, Alfred again sending ahead

[18]

interview questions (SO, interview 15), this time already with a strong focus on the film and visual art that he would focus on so much in his post-Nabokov career.

After a symposium at Berkeley in November 1970 where he had met Simon Karlinsky and other Nabokovians, Alfred proposed to Nabokov in February 1971 another Triquarterly special issue on the Russian emigration, this time with Karlinsky as his co-editor. A year later he was awarded a Guggenheim

Fellowship which would allow him to complete, he wrote, “an ever-expanding manuscript known officially, in grant-giving circles, as ‘Vladimir Nabokov: A Study’” (AA to VN, 22 February 1972). The Appels visited Montreux for five days in November 1972, where Véra asked Alfred why he didn’t warn them about Andrew Field, whose attitude while writing his biography of Nabokov had already begun to alarm them. A year later, after the Nabokovs had read Field’s manuscript and spent fraught months trying to reduce its errors, Alfred admitted he had wanted to warn them five years earlier, but hadn’t been asked and might have seemed self-interested (AA to VNs, 29 August 1973).

In May 1973 Nabokov wrote to Appel that he had “read with great interest your article on the flicks”—“Nabokov’s Dark Cinema,” in the Triquarterly special issue on émigré literature, also published as The Bitter Air of Exile: Russian Writers in the West, 1922-72 (1973)—“admiring your erudition but not

regretting the meagre influence, if any, that the cinema had on my work” (VN to AA, 14 May 1973). Appel explained six weeks later that this essay had originally been intended as a chapter in his half-finished book on Nabokov for McGraw-Hill and Guggenheim, but that he “got carried away (or inspired) and a new book was suddenly before me, amoeba-like,” and had already been accepted by Oxford, although he was “a bit depressed that the other book is still half-done” (AA to VN, 24 June 1973). Unlike Nabokov's Dark Cinema, the general study would remain unfinished.

[19]

In mid-July 1974 the Appels visited the Nabokovs for the last time, at Zermatt, where Nabokov was resting after completing Look at the Harlequins! but already reworking the French translation of Ada. On a path in the mountains, with the peak of Zermatt in the distance, Nina took the brilliant photograph of her old teacher and her husband pointing in opposite directions, as if neither could see what the other saw. In November, Nabokov thanked Alfred for Nabokov’s Dark Cinema, “a brilliant and delightful book,” although he had misgivings about being sometimes connected “with films and actors I have never seen in my life” and about what less subtle readers might suppose to be his direct borrowings from film (VN to AA, 8 November 1974). In reply Alfred explained his hope “that the good reader will realize that this book is finally about my mind ... and the ways in which high culture and the popular arts intertwine in one consciousness” (AA to VNs, 14 November 1974).

When he read Look at the Harlequins! on its publication at the end of 1974, Alfred disliked it intensely, feeling that it seemed to characterize Nabokov as the self-referential and self-obsessed writer his critics had portrayed him as all along. He never reread the novel, and apart from obituary tributes and memoirs, he never again wrote an essay on Nabokov. Nabokov had told him in the 1970s that he regretted that he could no longer set novels in the United States, because he was out of touch with American slang and other ephemera. Appel, who celebrated the merging of popular culture (advertisements, comics, films, popular songs) in Lolita and Pale Fire, himself came to feel that Nabokov had lost touch and lost much by his relocation to Europe.

In the summer of 1975 Nabokov succumbed to the first of the infections that would plague his last years. Appel, thirty-five years younger, himself had a heart attack in July 1976, while Nabokov was back in hospital with yet another infection. A year later Appel had recovered but Nabokov was dead. Alfred

[20]

spoke eloquently at the McGraw-Hill memorial in New York in July 1977, later expanding his memoir for the Times Literary Supplement and for Vladimir Nabokov: A Tribute (1979), edited by Peter Quennell.

Although he was deeply disappointed by Nabokov’s last completed novel and wrote no more critical essays on him, Alfred “never lost his enthusiasm for and admiration for Nabokov,” Nina Appel assured me recently. He moved in the new directions he opened up in the rush of inspiration that led to Nabokov’s Dark Cinema', writing in a personal vein, as in his first book after his heart attack, pointedly entitled Signs of Life (1983), and about the interrelationship between popular culture and high culture in the twentieth century. A former fine arts major, and already eagerly pursuing passions beyond literature, he had shown Nabokov some of Ansel Adams’ best landscape photographs at Zermatt in 1974: “A great artist!,” proclaimed Nabokov (Quennell, p. 15). Signs of Life shows how to read American photographs and the society they record.

1983 was the year I first met Alfred, at a Nabokov conference at Cornell in April. He was a delightful and difficult person at a conference. Delightful because he was so funny, difficult because he was so irrepressible: when he sat next to you he would wisecrack in your ear about what was being said on

stage, and it would be hard not to laugh even if you were trying to concentrate on the presentation. A week later I visited him in Wilmette, a lakeside suburb north of Chicago. His children, Karen and Richard, about whom he writes so proudly in the Annotated Lolita, had already left home. Nina, a law professor at Loyola, was about to become a singularly successful Dean of Law. Both Alfred and Nina regaled me gleefully with stories of the Nabokovs, Alfred appreciating especially his omnivorousness: “He could talk about anything and laugh about almost anything.”

I saw Alfred next at the Nabokov conference at Yale in February 1987. Occasionally I would call him from Chicago

[21]

airport on my way from or to New Zealand. In June 1991 he sent me the revised Annotated Lolita with the inscription: “For the greatest discovery since the Dead Sea Scrolls, p. 369” (the advertisement “See The Conquering Hero Comes—in a Viyella Robe!” with its picture of the man Lo identifies as a Humbert lookalike).

His next book, The Art of Celebration: Twentieth-Century Painting, Literature, Sculpture, Photography, and Jazz (1992), aimed to counter the sense of modernism and twentieth-century art in general as predominantly dark, bleak, and ironic. Alfred had begun his memorial tribute to Nabokov by stressing him as “a great and most resilient celebrant of life” (Quennell 11), and The Art of Celebration focuses on artists like Joyce, Picasso, Louis Armstrong and the Nabokov of “A Guide to Berlin”: “only eight pages long, but it can serve as a springboard, a quick way to gain an overview of the art of celebration, especially if you don’t have time to reread Ulysses” (114).

I last saw Alfred and Nina at the Nabokov Centenary celebration in April 1999 at the Town Hall, New York, where writers like Martin Amis, Joyce Carol Oates and Richard Ford were also paying tribute. Backstage, Alfred asked me anxiously, should he tell the “spooning” anecdote? Wouldn’t everybody know it? (Quennell 21; VNAY 578) I insisted he tell it: even if people knew it already, they would love to hear it again. Of course it brought the house down. Apart from Nabokov’s impromptu punchline, the most memorable line of the night was Alfred’s enthusiastic description of Nabokov: contrary to the impression so many had that he must be dauntingly haughty, “he was the most fun to be with of anybody I have ever met”—and this from the most untameably funny person I and others have ever met.

Despite having a son who became an opera singer, Nabokov notoriously did not care for music. He loved art, and the high finish of the best art. Partly because of its element of improvisation he especially disliked jazz. He has John Shade

[22]

write:

Now I shall speak of evil as none has

Spoken before. I loathe such things as jazz;

The white-hosed moron torturing a black

Bull, rayed with red; abstractist bric-a-brac;

Primitivist folk masks . . . .

Ironically the last book of Nabokov’s closest friend among his critics was Jazz Modernism: From Ellington and Armstrong to Matisse and Joyce, which Alfred published in 2002, two years after retiring from Northwestern. Jazz Modernism won the 2003 ASCAP Deems Taylor Award for outstanding coverage of music (“The first sustained attempt by any critic, musical or otherwise, to locate jazz in the larger context of modernism. Rarely if ever has a non-musician written about jazz so intelligently, and rarely has any musically trained critic brought to the study of jazz so wide a frame of cultural reference”—Commentary).

Nina Appel notes that Alfred’s “zest, humor and joy in his work continued his entire life.” At the time of his death he was working on two new books, one, Victory's Scrapbook, Warfare from Life, Leger and Hemingway to Dick Tracy, Picasso, and Me, on the effects of the propaganda readying American citizens for World War II, and the other on Louis Armstrong. Even the list of his books confirms Nabokov’s comment that Alfred was a “unique” (Quennell 21).

Unpublished material by Vladimir and Vera Nabokov quoted by permission of Dmitri Nabokov and © by the Nabokov Estate.

Unpublished material by Alfred Appel quoted by permission of Nina Appel.

[23]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

By Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to Priscilla Meyer at pmevertoweslevan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format; if by fax send to (860) 685-3465; if by mail, to Russian Department, 215 Fisk Hall, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459. All contributors must be current members of the Nabokov Society. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Notes may be sent, anonymously, to a reader for review. If accepted for publication, the piece may undergo some slight editorial alterations. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (footnotes incorporated within the text, American punctuation, single space after periods, signature: name, place, etc.) used in this section.

NABOKOV’S LOLITA AND FROST’S “DESIGN”: A “WITCHES’ BROTH” OF COINCIDENCE

In “Frost and Shade, and Questions of Design” (Nabokovian 56 [2006], 19-27), Anna Morlan discusses Nabokov’s use of Robert Frost’s poetry in the novel Pale Fire, specifically John Shade’s poem, which Morlan sees as “Nabokov’s homage to Frost and also his take on some of the issues raised by Robert Frost throughout the volume of his poetry” (19). I will extend Morlan’s argument to Lolita and limit it only to Frost’s poem “Design.” While Morlan claims that, in Pale Fire, Shade’s idea of “design is not one of darkness, but of sense, a game which fills the world with playfulness and provides him some certainty” (27), the opposite proves true in Lolita—Humbert

[24]

Humbert’s design is clearly one of “darkness,” marking this novel as more cynical in tone and less hopeful, less assured in its questions of greater or transcendent meaning.

While Nabokov most often directly references Frost in Pale Fire and Poe in Lolita, thematically, Lolita comes closest to the majority of Frost’s nature poems, which reflect the ambivalence, even malevolence, in the “design” of the natural world.

“Design” (1922) is one of Frost’s poems (such as “Mending Wall,” “Birches,” or “The Need of Being Versed in Country Things,” to name a few) that consider the pathetic fallacy, the projection of man’s inner feelings upon the world around him and his need for patterns of meaning (or “design”) in what he observes. Nabokov often shares this thematic concern with Frost, constructing narrators who look to their surroundings for affirmation, condemnation, or “signs and symbols.” In “Design” Frost creates a poetic persona who, in commenting on his environment, reveals the deceptively simple, yet cruel, coincidence that allows a predatory spider to capture its prey:

I found a dimpled spider, fat and white,

On a white heal-all, holding up a moth

Like a white piece of rigid satin cloth—

Assorted characters of death and blight

Mixed ready to begin the morning right,

Like the ingredients of a witches’ broth—

A snow-drop spider, a flower like a froth,

And dead wings carried like a paper kite.What had that flower to do with being white,

The wayside blue and innocent heal-all?

What brought the kindred spider to that height,

Then steered the white moth thither in the night?

What but design of darkness to appall?—

If design govern in a thing so small.

[25]

– (The Road Not Taken, Ed. Louis Untermeyer, New York: Henry Holt, 1971,202)

The following significant passage from Lolita, in which Humbert describes a rainy morning in the Haze household, seems to be an indirect homage to Frost’s poem:

My white pajamas have a lilac design on the back. I am like one of those inflated pale spiders you see in old gardens.

Sitting in the middle of a luminous web and giving little jerks to this or that strand. My web is spread all over the

house as I listen from my chair where I sit like a wily wizard. Is Lo in her room? Gently I tug on the silk. She is

not. [...] one has to feel elsewhere about the house for the beautiful warm-colored prey. (49, emphasis added)

The confluence of the white spider, the rare white heal-all, and the white moth bring about the moth’s doom, much as the convergence of Humbert the predator with young Lolita in sunny Ramsdale will trap her in her lamentable destiny. This “witches’ broth” (6) of coincidence does not make, as in Pale Fire, a “web of sense” but an overwhelming feeling of an insidious design; as Frost’s narrator feels the capricious hand of chance behind the death of the moth, so we too feel the “darkness” of the designs upon young Lolita. We see the results of these designs when, acknowledging the role of accident, of simple bad luck, in Lolita’s unimaginably unhappy existence, Humbert observes her face reflecting “a kind of dull amazement at the curiously inane life we all had rigged up for her” (Nabokov 215); Lolita, much like Frost’s moth, finds her life becoming an intractable snare of inexplicable suffering.

The web of “Fate scheming” (50) continues to spread throughout Humbert’s narration, and a mere three pages after describing his spider-like morning habits, he will present his reader with the first mention of what he playfully calls

[26]

“McFate” (52), which he defines as “that devil of mine,” the force outside himself that toys with him, initially keeping Lolita out of his clutches and later causing him to lose her (56). As readers, of course, we see “McFate” most often working in Humbert’s favor against Lolita, the will of the bloated spider overtaking the fluttery life of the moth. Even Miss Phalen (“moth” from the French, as Appel tells us in his Notes, 364), Lolita’s potential ally against Humbert’s designs on her, has been caught in another of McFate’s webs, breaking “her hip in Savannah, Ga., on the very day [Humbert] arrived in Ramsdale” (56). Despite his protestations to the contrary, these hints and clues about Humbert’s role as predator—working more in conjunction with McFate, with this “design of darkness,” than against it (Frost, line 13)—reveal the possible brutality of chance, the sometimes random, senseless accident, such as the murder of John Shade or the assassination of Nabokov’s own father.

While Humbert, much like Frost’s poetic persona, addresses the nature of destiny, of fate, throughout the novel, his ruminations in chapter thirty-one of part two are probably the most telling. Here Humbert claims that “in a moment of metaphysical curiosity” he “had hoped to deduce from [his] sense of sin the existence of a Supreme Being,” the final arbiter in the court of McFate (Nabokov 282). Conferring with a priest on ‘frosty mornings in rime-laced Quebec,” Humbert cannot reconcile religion with the world he knows (282, emphasis added). These mornings, Humbert is indeed Frost-like in his search for “design,” and, like Frost’s narrator, he retains his uncertainty. Looking back upon his time with Lolita, this child who is but a “thing so small” (Frost line 14), Humbert claims:

Unless it can be proven to me....that in the infinite run it does not matter a jot that a North American girl-child

named Dolores Haze had been deprived of her childhood

[27]

by a maniac, unless this can be proven (and if it can, then life is a joke), I see nothing for the treatment of my misery

but the melancholy and very local palliative of articulate art.

– (Nabokov 283)

Humbert’s inquisitive stance in this section is similar to the series of questions Frost’s narrator poses at the end of “Design” when he wonders “what brought” (line 11) the flower to be white, the white spider to the flower, and the white moth to the spider’s web. Does “design govern” in nature (14)—or in the life of a nymphet? Humbert’s calling us back to “art” as the final moral “palliative” for his condition brings to mind the fact that Nabokov is the absolute “designer” here, the Supreme Being governing Humbert’s life, or, as Morlan explains, “ultimately [Frost is] the one who designs a web on the page that brings about the death of the moth. In the end, his design is beautiful but harsh, and the only playfulness that Frost finds is that which he as poet brings into it” (25). I would argue that this type of poet’s playfulness is primarily what we find in Lolita as well—not exactly the “sly playfulness” Nabokov found in nature (or created in Pale Fire) but the very human, self-reflexive, ability to create webs of meaning. As Brian Boyd reminds us, Nabokov was “fascinated by deception in nature, especially mimicry” and he “liked to find in his art equivalents for the sly playfulness he sensed behind things” (‘“Even Homais Nods’: Nabokov’s Fallibility; or, How to Revise Lolita” Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita; A Casebook, Ed. Ellen Pifer. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003, 58). The poetic playfulness of Frost in “Design” or of Nabokov in Lolita highlights the seriousness of art, of human endeavor; Humbert’s parody of humanity, his grotesque imitation of fatherhood, is no less meaningful than the mischievous “deceptions” of nature.

In the end, these types of playfulness—that of nature and that of the poet—are not mutually exclusive but can combine

[28]

to add to the richness and texture of the artists’ works. In Lolita, these layers do not allow for the kind of transcendent reassurance John Shade finds in Pale Fire; instead, Nabokov seems to abandon the possible comforts of design to emphasize the uncertainty and misfortune of fate in tracing the life of “blue and innocent” Dolores Haze (Frost, line 10). Like Frost, Nabokov was interested in the paradoxes—and sometimes the absurdities—found in nature, as well as what Louis Untermeyer calls “the paradox of people” and “the contradictory nature of man” (The Road Not Taken 111). As he describes his own “paradise whose skies were the color of hell-flames” (Nabokov 166), Humbert certainly seems an embodiment of man’s contradictory nature, suggesting, with his “paradise,” not the precariousness of life after death, but the bewildering calamities of the world we inhabit and the power of the imagination to form the lives we live.

—Misty Jameson, Greenwood, South Carolina

CASTOR AND POLLUX IN PALE FIRE

"... The Moon follows the Sim like a French

Translation of a Russian poet. ”

“Variations on a Summer Day ”

Wallace Stevens“I imitate the Saviour,

And cultivate a beaver.”

“Antic Hay”

Aldous Huxley

[29]

An uncommon word shared by Nabokov and another author is, most often, the key to a wealth of hidden references in his novels. It may also happen that a common word is applied by him to mislead the reader. Pale Fire’s pale fires may serve to indicate different sources of light, mythological references, spiritualistic seances, literary works or, perhaps, all of these at once. Readers should trust Kinbote’s interventions, although not literally. For example, why would Kinbote observe that his “silly cognomen” (the Great Beaver) “was not worth noticing” if not to call our attention to it?

Castor means “beaver” in both Greek and Latin and it is the name of one of the twins in Greek mythology, Castor and Pollux. Their names designate two stars in the constellation of Gemini and the patrons of sailors, who derive portents from electromagnetic phenomena also recognized as “Castor and Pollux.” In Kinbote’s commentaries there are several indications which suggest the importance of their names, both in connection to mysterious fires and as a hidden reference to the libretto for Rameau’s lyrical tragedy, “Castor and Pollux.” These two items lead to a secondary attribution to the novel’s name, besides the one Shade invokes, a “moondrop title. Help me, Will! Pale Fire,” for his work.

“Pale Fire,” the poem, is described by its characters as being: (a) something “pale and diaphanous, ” “a transparent thingum, ” ie: a feeble light, irrespective of its causation; (b) in need of a “moondrop” title; (c) comparable to the satellite whose light reflects or robs the fire of a sun, i. e.: it is undecided if Shade’s poem reflects CK’s story, Shakespeare’s plays or poems by Robert Frost; (d) a description of a “crystal land,” related to

[30]

Zembla, perhaps like “crystal to crystal”; (e) a poem whose structure bears a crystal symmetry and “predictable growth.”

Kinbote’s images are curiously mingled when he returns to the (Shakespearean) sun-moon orbs of heat and light, for he may consider that Zembla and himself are the sun, whereas Shade is in the position of the moon by suggesting that (a) PF sheds a waning moon’s diaphanous light and seeing himself as the steady sun (“Although I realize only too clearly, alas, that the result, in its pale and diaphanous final phase, cannot be regarded as a direct echo of my narrative...”); (b) his Zemblan story not only glows like the sun, but it warms Shade into a boiling bubbling point (“one can hardly doubt that the sunset glow of the story acted as a catalytic agent upon the very process of the sustained creative effervescence”); (c) his effect on Shade engenders a resemblance in color and hue, i.e. it must be closer to ice crystals/moonlight than to sun/moon (“a symptomatic family resemblance in the coloration of both poem and story”). Nevertheless, Kinbote has also compared himself to the moon which borrows its light from Shade’s sun (“in many cases have caught myself borrowing a kind of opalescent light from my poet’s fiery orb”).

There are other kinds of reflections and pale fires in Nabokov’s novel. In the Foreword, CK testifies to Shade’s burning a batch of cards “in the pale fire of the incinerator.” There are magic circlets of light enticing Shade’s daughter, Hazel, into spiritualistic research. Although we find, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, “The glow-worm shows the matin to be near, And gins to pale his uneffectual fire, ” (mentioned by Peter Lubin, 1970, “Kickshaw and Motley,” A. Appel & Newman ed.) and in “The Tempest,” a reference to a meteor which may appear as a single flame, a will-o-the wisp, or a double fire (when it is called “Castor and Pollux”), it is generally assumed that the title of the novel, like Shade’s poem, is solely inspired by Shakespeare’s lines: “The moon’s an arrant thief, / And her pale fire she snatches from the sun” (Act IV, Scene 3 in “Timon of Athens”).

[31]

III

The French words for “pale fire” (pâle flambeau) were first mentioned by Priscilla Meyer, in “Find What the Sailor Has Hidden” (Wesleyan University Press, 1988, 170-174), when she discusses some of the references in Kinbote’s note to line 80. In his commentary Kinbote cites A. R. Wallace, a scientist who, like Charles Darwin, described the theory of “the survival of the fittest,” before he links Wallace and spiritualism: “The Countess...had him attend table-turning seances ...at which the Queen’s spirit, operating the same kind of planchette she had used in her lifetime to chat with Thormodus Torfaeus and A.R. Wallace, now briskly wrote in English: “Charles take take cherish love flower flower flower” (Cp. CK’s note to line 347, on Hazel’s experiment with the moving circlet of light that responded with “broken words and meaningless syllables... pada ata lane pad not ogo old wart alan ther tale feur far rant lant tal told”).

Meyer also quotes Kinbote’s note to line 549, with its long and atypical dialogue, when “Shade takes the materialist position and Kinbote is aligned with Wallace” (Meyer 171). The first lines she quotes are: “Shade: Personally, I am with the old snuff-takers: L ’homme est né bon.’’’’

The outline of two additional hidden references is here discernible. When Kinbote resorts to twenty-two reported ex-changes between himself and Shade, he seems to be parodying the style of Denis Diderot, particularly “Le Neveu de Rameau,” which contains similar dialogues between a philosopher and Rameau’s nephew, discussing moral and religious issues, friendship and patriotism. He is also introducing the musician Rameau, although neither Diderot nor Rameau is directly mentioned in Pale Fire. Nor is there a reference to yet a third French composer and philosopher, J. J Rousseau, even though the lines espoused by Shade, “l’homme est né bon," doubtlessly point to the latter.

[32]

If Shade is indeed referring to Rousseau’s famous ideal “good savage,” Kinbote is relating to Wallace, and to his spiritualistic investigations. According to Meyer (172-173), “Wallace recorded the proceedings of the many seances he attended” and he offers a long message, in French, dated August 1893, purportedly sent by a dying Napoleon III to a medium who signed the poem as ‘Esprit C.’”

The lines Meyer quotes are: “Où vais-je?..../Des bords du lit funèbre, ou palpite sa proie/Aux lugubres clartés de son pâle flambeau,/L’impitoyable mort me montre le tombeau./ Éternité profonde...” In the libretto of Jean-Phillipe Rameau’s lyrical tragedy, “Castor et Pollux” (1737), written by Pierre-Joseph Bernard, we also encounter a “pâle flambeau,” the pale fire of mortal decomposition, applicable to Castor, a dead hero. It is worth remembering that Diderot and Rousseau are ranked among the first anarchists and that they stand in opposition to classic Voltaire and Rameau, with whom Rousseau had established an open rivalry.

It is impossible to ascertain if the reference to Rousseau indicates VN’s knowledge of Rousseau’s opposition to Rameau, or of Bernard’s libretto for “Castor and Pollux.” The links with Wallace are clear, as is his reference to a poem “taken down by a medium.” And yet, independently of VN’s knowledge about the two seventeenth century musicians and philosopher, we must realize that the lines the “Ésprit C” wrote were inspired by the libretto for “Castor et Pollux.” There are too many words in common between their few lines (flambeaux, tombeau, lugubre, clartés, funèbres). We have here a clearly demonstrable hoax, which may have taken Wallace in, but not Kinbote who parodies the belief in spiritual messages derived from moving lights. By mentioning his cognomen, “The Great Beaver,” and referring to Rousseau and Wallace, Kinbote may be pointing to Rameau’s libretto, away from Shakespeare’s sun and moon evoked by John Shade.

In Rameau’s “Castor and Pollux” (Act II, Scene 2) Télaire,

[33]

whose father is the sun, exclaims: “Tristes apprêts, pâles flambeaux, / Jour plus affreux que les ténèbres / Astres lugubres des tombeaux, / Non, je ne verrai plus que vos clartés funèbres. / Toi, qui vois mon cœur éperdu, / Père du jour, 6 soleil, 6 mon père ! / Je ne veux plus d’un bien que Castor / Et je renonce à la lumière.”

As mentioned in the beginning of the present note, the circlet of light that sends warning messages to Hazel might be considered a “will-o-the-wisp” (the spirit-light denies this attribution following one of Hazel’s enquiries) or represent a “Fire of St. Elm” or the “Castor and Pollux” electromagnetic phenomena with their magical connotations. To all appearances Kinbote has failed to recognize Shade’s chosen title in Shakespeare since, as he informs us, all he’s managed to carry to his “Timon cave” has been “a tiny vest pocket edition of “Timon of Athens”— in Zemblan! It certainly contains nothing that could be regarded as an equivalent of "pale fire" (if it had, my luck would have been a statistical monster).” The passage he selects, from which “pale fire” has disappeared, is a retranslation into English by Conmal: “The sun is a thief: she lures the sea / and robs it. The moon is a thief: / he steals his silvery light from the sun. / The sea is a thief: it dissolves the moon.” Rameau’s envious nephew, from Diderot’s dialogues, once exclaimed: "si un voleur vole I’autre, le diable s ’en rit.” Perhaps the devil is laughing at Kinbote’s hoaxes and thefts or at his opalescent blind-spots, or Nabokov is sharing his mirth with the reader by jostling him back and forth between truth and fiction, authentic references and hoaxes.

I thank Priscilla Meyer for her generous editorial advice and Mércia Pinto, Jacob Wilkenfeld, Luiz Fernando Gallego and Abdellah Bouazza (who also brought up in the Nabokov-List the lines by Wallace Stevens, quoted in the epigraph) for their invaluable help with the bibliography.

—Jansy Berndt de Souza Mello, Brasilia, Brazil

[34]

BAUDELAIRE, MELMOTH AND LAUGHTER

Humbert Humbert refers to his car as a “Dream Blue Melmoth” (Annotated Lolita 227). Near the end of the novel, Humbert draws further attention to the name of this car by parenthetically saying hello to it from the text: “Hi, Melmoth, thanks a lot, old fellow” (307). Why Melmoth? The Annotated Lolita explains that “Melmoth” is a reference to both Charles Robert Maturin’s large Gothic novel Melmoth the Wanderer and to Oscar Wilde’s “post-prison pseudonym” Sebastian Melmoth. Nabokov playfully adds another reference: “Melmoth may come from Mellonella Moth (which breeds in beehives) or, more likely, from Meal Moth (which breeds in grain)” (416-417). These three possibilities do not really have great resonance within the novel. They do not quite explain why Nabokov (or Humbert) would choose the name Melmoth. In fact, the name seems to have greater resonance in yet another source, Charles Baudelaire’s essay “On the Essence of Laughter” (ed. and trans. Jonathan Mayne, New York: Phaidon, 1964, 147-165).

Baudelaire’s analysis of laughter contains ideas that can be connected to Humbert and to some themes of Lolita. Baudelaire describes the laughter of the man who lives with a sense of his own superiority: “this laughter ... is – you must understand – the necessary resultant of his own double nature, which is infinitely great in relation to man, and infinitely vile and base in relation to absolute Truth and Justice. Melmoth is a living contradiction” (153). Here we have one of Nabokov’s favorite themes, the double-a theme that is clearly expressed by Humbert’s double name. More specifically, we have a sense of Humbert’s character, a man who feels superior to others and, at the same time, commits actions that are “vile and base.” Brian Boyd describes Humbert’s doubleness: “Humbert might wish to introduce Lolita to Baudelaire or Shakespeare, but his false relationship to her, his breach of her mother’s trust, and his

[35]

crushing of her freedom mean he can only stunt her growth” (Vladimir Nabokov, The American Years, 1991, 6). In fact, this doubleness – or as Baudelaire states, this “living contradiction”– can in part explain the moral difficulty that many readers have with this novel. A number of scholars have discussed this theme of the double, often focusing on Humbert’s apparent doppelganger Quilty; reading with Baudelaire’s thoughts in mind (and Boyd’s), one can see the double within Humbert alone.

Baudelaire goes on to describe the “satanic” laughter of Melmoth, in a sentence that could be read as an insightful analysis of Humbert’s text: “And thus the laughter of Melmoth, which is the highest expression of pride, is forever performing its function as it lacerates and scorches the lips of the laugher for whose sins there can be no remission” (153). Humbert, too, has a pride that lacerates, an arrogance that is thoroughly bound up in his sense of guilt. His “sin” is his “soul”(9). An essay on laughter might seem an odd place to find insight into Humbert, a man who is not prone to great laughter. Nabokov sees Baudelaire’s essential ideas, keeps the point about a sense of superiority and removes the actual laughter – that is, unless one senses some disturbing laughter coming from the entirety of Humbert’s text.

The locale of Humbert’s writing also has some resonance in Baudelaire’s essay. Humbert begins writing this text “in the

psychopathic ward,” and he remains in an ambiguous “legal captivity” (308, 3). Baudelaire writes, “[I]t is a notorious fact that all madmen in asylums have an excessively overdeveloped idea of their own superiority: I hardly know of any who suffer from the madness of humility” (152). This too could be seen as a Baudelairean reading of Humbert, who in a previous “bout with insanity” had found “an endless source of robust enjoyment in trifling with psychiatrists” (34). Note Baudelaire’s description of “Satanic” laughter: “Laughter, they say, comes from a sense of superiority. I should not be surprised if, on making this discovery, the physiologist had burst out laughing himself at

[36]

the thought of his own superiority” (152). Humbert Humbert shares this sense of superiority as well as the self-awareness; Baudelaire sees something Satanic in that sense of superiority, and he also connects this to Melmoth, who he refers to as “that great satanic creation of the Reverend Maturin” (153).

It would be appropriate to Humbert, the author of a “comparative history of French literature for English-speaking students” (32), to think of Baudelaire when using the name Melmoth and comically (or madly) saying hello to his car. In addition, Nabokov apparently had little respect for Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer, stating that “Maturin used up all the platitudes of Satanism, while remaining on the side of the conventional angels” (EO, II, 352). (This comes from Nabokov’s note on “Melmoth” in his annotations of Eugene Onegin. Nabokov quotes Baudelaire’s praise of Maturin’s novel toward the end of that note, as though he associates Melmoth with Baudelaire.) Any reference to Oscar Wilde would be less relevant to this novel (and to Humbert) than the presence of Baudelaire. And the idea that the name has to do with a real moth (or two) is most likely some misleading information planted by Nabokov. Appel’s annotations state the “Melmoth” is “a triple allusion” (416), but he docs not explain how any of these three allusions (Maturin, Wilde, or moths) add to the texture of the novel. Baudelaire’s sense of Melmoth is more suited to Lolita.

Of course, Nabokov refers to Baudelaire in other works as well. Baudelaire’s L ’Invitation au voyage is directly referenced in the title of Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading, and elsewhere in the novel, as Gavriel Shapiro and other scholars have pointed out. There is a telling moment in Baudelaire’s “On the Essence of Laughter” that may have been in Nabokov’s mind when writing the conclusion of his Invitation. Baudelaire describes a scene in which “the English Pierrot” is beheaded:

His head was severed from his neck-a great red and white head, which rolled noisily to rest in front of the prompter’s

[37]

box, showing the bleeding disk of the neck, the split vertebrae and all the details of a piece of butcher’s meat just dressed

for the counter. And then, all of a sudden, the decapitated trunk, moved by its irresistible obsession with theft, jumped

to its feet, triumphantly “lifted” its own head as though it was a ham or a bottle of wine...(161)

Nabokov adds a metaphysical dimension to the scene where Cincinnatus arises from his decapitation. Cincinnatus moves toward his double, toward a place that may have a greater sense of “Truth and Justice,” and away from the “base and vile” prison in which he had existed (to use Baudelaire’s terms in describing the double, quoted above). Cincinnatus leaves his head behind. Again, Nabokov removes the direct sense of laughter, and adds a dimension that is not present in Baudelaire’s description. Nonetheless, Nabokov seems to have read Baudelaire’s essay attentively.

This is certainly true when one reads Baudelaire’s thoughts on the laughter of children: “the laughter of children.. .is altogether different, even as a physical expression, even as a form... from the terrible laughter of Melmoth – of Melmoth, the outcast of society, wandering somewhere between the last boundaries of the territory of mankind and the frontiers of the higher life” (156). Here we have that final scene of Lolita, where Humbert rests high on a mountain road and listens to the sounds of children at play, which includes “an almost articulate spurt of vivid laughter” (308). Baudelaire continues: “For the laughter of children is like the blossoming of a flower. It is the joy of receiving, the joy of breathing, the joy of contemplating, of living, of growing.” This is exactly what Humbert hears (“the melody of children at play”), and exactly, he realizes, what Lolita has been absent from. Baudelaire writes, “Joy is a unity”; Humbert writes, “[T]hese sounds were of one nature.” Nabokov also adds a Baudelairean exclamation aimed at the reader during this scene: “Reader!” (308). The Annotated Lolita explains in

[38]

an earlier note that this direct appeal to the reader “echo[es] the last line of Au Lecteur, the prefatory poem in Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du mal” (436).

Interestingly, Humbert keeps this moment pure. Many readers have used this as evidence of Humbert’s knowledge of his crime, perhaps of his sense of guilt or his transformation toward love. Some have gone so far as to judge Humbert with less contempt because of this moment (although one should note that this scene does not happen at the end of the story: Humbert only places it at the end, perhaps to manipulate the reader into being more lenient). Baudelaire, however, does not think of this laughter as so pure: “the laughter of children... is not entirely exempt from ambition, as is only proper to little scraps of men-that is, to budding Satans” (156). Baudelaire seems more cynical than Humbert here, as he sees budding Humberts – budding Melmoths – in that laughter. Humbert, on the other hand, depicts such laughter as something entirely separate from himself.

There is plenty of evidence of Nabokov’s interest in Baudelaire, as explained by scholars not mentioned in this brief article, such as John Burt Foster, Jr., and Robert Alter. My purpose is merely to offer a small addition to that work. There is certainly some affinity between Nabokov’s work and Baudelaire’s “On the Essence of Laughter.” Jorge Luis Borges writes that we create our own precursors: one who knows Nabokov cannot read “On the Essence of Laughter” without seeing some Nabokovian ideas. In a more chronological sense, Baudelaire’s essay may have inspired the name of a car.

—David Rutledge, New Orleans

[39]

“MOUNTAIN, NOT FOUNTAIN ,” PALE FIRE’S SAVING GRACE

Canto III of John Shade’s poem “Pale Fire” may surprise the reader for a number of reasons What exactly “dawned” on Shade after he learned about the misprint which destroyed the “robust truth” he derived from the “twin display” of the white fountain? And why did he experience “something ... of ... Pleasure” after he had just finished Canto II, containing the story of his daughter’s suicide?

The clue to the answers to both questions may be found in the white mountains Mrs. Z. and Shade envisaged; Mrs. Z. in her near-death dreamlike vision, Shade in his poetry. These mountains owe their whiteness to snow and ice. And as they are enveloped by a “veil,” they seem to act as agents capable of showing water in all its manifestations, from gaseous to crystallized forms. The single line Kinbote quotes from Shade’s poem “Mont Blanc” refers, through its images and its style, to the Romantic Poets who have celebrated high mountains for similar qualities, such as the splendor of sun-reflecting snow, and the evocation of eternity to which these mountains seem to belong. The various states of water-gaseous, liquid and solid-and its movements result from the interference by the sun and the moon, the orbiting of our planet, and its atmospheric conditions, thus establishing manifold links with the universe.

The powerful image of the “rain puddle” Nabokov presents in Bend Sinister, which is “shaped like a cell that is about to divide,” not only symbolizes the regenerating force of life, but its promise of an afterlife as well. This is because of the puddle’s narrow bottleneck which thinly connects metaphorically this world with the otherworld. Charles Sherrington’s explorations into the origin of life are mentioned to show how well-founded Nabokov’s related notions are.

Many of Nabokov’s heroines are drowned, others like Irma in Laughter in the Dark notice the various forms of the aqueous

[40]

medium and its communications with light and lightning. Hazel Shade, disappearing in a neck, which, as an isthmus, is suggestive of the possible link between the two worlds, is surrounded by water in all its states, as well as by miniature “sun-creamed domes” which her father describes in his poem “Mont Blanc.”

The aim of this paper is by no means to present Nabokov as a kind of modem Thales. Indeed, suggesting that Nabokov’s metaphysics, about which we know hardly anything, may somehow be condensed in “water,” would be a dismal reductio ad absardum. It is rather the dazzling display of Nabokov’s many marvelous images and their interlacement, superposed on the beauties already discovered by the Romantic poets and Alexander Pope, that I would like to highlight.

The leap that Shade makes from disappointment (after Coates ’ disclosure of the misprint in lines 801-2) to contentment by apprehending the contrapuntal theme is so apodictic that it seems to require some clarification to make this conversion comprehensible. Nabokov often hides the “elegant solutions” for his riddles in the very phrases he uses to detail these riddles (Strong Opinions 16). The acrostic in “The Vane Sisters” illustrates this as does the remark by Falter, who has solved “the riddle of the universe,” to Sineusov who is after its solutions: “I inadvertently gave myself away” (Stories 518).

Shade pays a visit to Mrs. Z. expecting to receive confirmation of the near-death vision they both had, which included a white fountain. But, alas, she never saw the fountain: she saw a white mountain. Shade, driving home, thinks about abandoning his lifelong pursuit of everlasting life, but suddenly realizes “that this / Was the real point, the contrapuntal theme” he had been looking for with so much persistence (P 806-7; Pale Fire is referred to by using the letters F, P, C and I for its Foreword, Poem, Commentary and Index and by the numbers of the poem’s lines). What had dawned on Shade we can learn from Kinbote’s comments on line 802. Kinbote here informs his readers that “[t]he passage 797-809, on the poet’s

[41]

sixty-fifth card, was composed between the sunset of July 18 and the dawn of July 19.” As Shade “preserved the date of the actual creation” by noting it on “the pink upper line” of the index cards he used, and as the lines mentioned, including the skipped one “to indicate double space” exactly match “the fourteen light-blue lines” available on these cards, Kinbote’s information appears to be accurate (F). Asked by Kinbote ‘“what were you writing about last night, John?’” the poet answers: “’Mountains’” (C 802). The actual lines written at that time comprise precisely the switch from disillusionment due to the misprint, to Shade’s reaching “the real point,” and contain no “mountains” at all, apart from the misprinted one: “[m]ountain, not fountain.'’’ But of course Shade is right; the lines 797-809 are essentially about mountains, as these restore the “twin display” that would provide Shade the “robust truth” of the existence of the hereafter (P 746; 766). Shade must have realized that not he but Mrs. Z. must have noticed this unique coincidence by combining her own “white mountain” with Shade’s “white mountain,” envisaged in his poem “Mont Blanc” (P 782-83; C 782). If the mountain in Shade’s poem resembles that of Mrs. Z.’s vision and if the poem pertains to the hereafter, that is, if Shade’s “Mont Blanc” somehow has prefigured that of Mrs. Z.’s vision, then the recurrence Shade counted on would have been regained.

Unfortunately, the reader is only given “one line” from Shade’s poem: Mont Blanc’s “blue-shaded buttresses and sun-creamed domes” (I; C 782). Luckily, the two colors of this line, the blue and the implied white of the cream, mirror those in the lines devoted to Mrs. Z. who sees a “white” mountain and has “blue hair” (P 758; 771), and reads about Shade’s poem “Mon Blon” in the “Blue Review” (P 783; 782). Moreover, the line cited from Shade’s “Mont Blanc” has two collocations (forms frequently used by the Romantic poets), while “Pale Fire” has only two collocations in all its 999 lines: “flax-haired” and “ink-blue” (P 574; 995), yielding another combination of blue and

[42]

(yellowish) white. Furthermore, all or most of Shade’s shorter poems presented or mentioned in Pale Fire have transcendental subjects or intentions: “The Sacred Tree,” “The Swing,” “Mountain View,” “The Nature of Electricity” (I). (From “April Rain” there is only one line: “A rapid pencil sketch of Spring,” C 470). “The Sacred Tree” is about a ginkgo leaf, which tree is considered sacred in China and associated with eternity. In “The Swing” the final stanza is about “The empty little swing ... /That break[s] my heart,” a reference to the swing of Shade’s “little daughter” whose ghost is suggested in line 57 (C 61). “The Nature of Electricity” is a lyrical meditation on the chance that deceased souls continue to live by residing in electricity. In “Mountain View” a mountain is admired when the poet who has reveled in its view, realizes that

... we all know it cannot last,

The mountain is too weak to wait—,

clearly a reference to eternity, the only dimension that can outlast a mountain (C 92). In Canto three, Shade, while discussing the

“Institute of Preparation for the Hereafter,” cheerfully recalls the view of “a snowy form” o f a great mountain, strongly suggesting that gazing at a nebulous white mountain is a better preparation for the hereafter than President McAber’s Institute (P 513).

Mrs. Z. sees her white mountain beyond a “veil” whereas Shade sees his mountain beyond a “veil of blue amorous gauze” (P 751; C 92), and both notice trees, an orchard in Mrs. Z.’s case, pines in Shade’s poem. Shade’s three poetical evocations of mountains (lines 510-14; “Mountain View” and “Mont Blanc”) share the veil, the trees, the snow and the mountain’s grandness with Mrs. Z.’s mountain. Shade must have realized that the recurrence of these features, all part of what his imagination created as the vista of the hereafter, is a much better validation than a mere repetition of a moribund vision. That his powerful imagination, engrossed in creativity “on the highest terrace of

[43]

consciousness” could have matched the vision of Mrs. Z., whose consciousness even when fully restored to life was somewhat

enervated, must have convinced Shade of the veracity of this image {Speak, Memory, 50). \wAda Nabokov called “individual

magically detailed imagination” the “third sight,” thus ranking it above the perception of supernatural phenomena (second sight) or plain observation (252).

The love of great mountains has not been widespread in all ages. Thomas Gray was one of the first to become enraptured (instead of repelled) by the sight of mountainous scenery (see Leslie Stephen, “Gray and his School” in Hours in a Library, volume 3). In the Romantic Age the love of great mountains reached its peak. Wordsworth was a restless walker and Coleridge a reckless climber, and they, like Shelley and Byron, wrote poems inspired by the awe the Alps evoked. The view of peaks covered with eternal snow prompted reflections on the creation and the limits of earthly life, as the highest summits seem to support or even to pierce the sky. It is indisputable that Shade, entitling his poem “Mont Blanc,” was aware, in every detail, of Shelley’s great example, one of his best known lyrics. (See also Matthew Roth, “Glimmers of Shelley in John Shade's Verse,” The Nabokovian, 2009, 62). Shelley’s “Mont Blanc” has two striking images, a mountain beyond a veil as well as a waterfall with a veil:

Thine earthly rainbow stretched across the sweep

Of the aethereal waterfall, whose veil

Robes some unsculptured image ... (25-27)...I look on high;

Has some unknown omnipotence unfurled

The veil of life and death? (52-54)

As is clearly suggested in the lines cited, this veil covers a

different world:

[44]

Some say that gleams of a remoter world

Visit the soul in sleep,-that death is slumber. (49-50)

Apart from the phrase “’The Land Beyond the Veil” (P 750-51), Shade uses the image of “sun-creamed domes” in his “Mont Blanc.” “Veil” and “dome” are words that typically belong to the vocabulary of the Romantics. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein the eponymous protagonist, living in the Alps and eager to learn “the secrets of heaven and earth,” complains that even the most learned philosopher had only “partially unveiled the face of Nature” (New York: New American Library, 1965, 37,39). Wordsworth wrote how he beheld “Unveiled the summit of Mont Blanc” {The Prelude, IV, 525), and Byron provides another example: