Download PDF of Number 57 (Fall 2006) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 57 Fall 2006

____________________________________

CONTENTS

News

by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Notes and Brief Commentaries

by Priscilla Meyer 5

‘“Old, Mad, Gray Nijinsky’ in Lolita”

– Monica Manolescu 5

“Pnin/Pnin’s Search for

– Maria-Ruxanda Bontila 9

“What Troubled Chekalinsky?”

– Sergey Karpukhin 14

“Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross

in The Gift”

– Gavriel Shapiro 18

“Painting and Punning: Cynthia’s and

Sybil’s Influence in “The Vane Sisters”

–Misty Hickson Reynolds 22

“Gradus Amoris”

–John A. Rea 30

“Nabokov’s Pencil”

–Priscilla Meyer and Gene Barabtarlo 35

Russian Poets and Potentates as Scots and

Scandinavians in Ada: Three “Tartar” Poets

Part Two

by Alexey Sklyarenko 39

Annotations to Ada: 27. Part I Chapter 27

First Section

by Brian Boyd 58

2005 Nabokov Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker and Kelly Knickmeier 77

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 57, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

- Brian Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada” (because superseded by, updated, hyperlinked and freely available on, his website AdaOnline).

In some but not all cases the downloadable pdf version of the print Nabokovian will have the annual bibliography and the “Annotations to Ada.”

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Nabokov Society News

Reminder: Because of printing and postal rate increases over the past seven years, the membership/subscription rates for The Nabokovian have been modestly raised: individuals ,$19 per year; institutions, $24 per year. For surface postage outside the US A add $ 10; for airmail add $14. These are the first increases in seven years.

*****

Odds and Ends

– The offices of Smith/Skolnik, agents for the Nabokov literary estate, forward the following excerpt from a Fall 2006 announcement of the first significant Russian publishing agreement reached since Russian copyright law was revised in 2004.

“Dmitri Nabokov has now signed an agreement with Maxim Kriutchenko of St. Petersburg publisher Azbooka for publication of the works of his father. Discussions with Azbooka began in 2004 when the Russian Federation set aside Soviet laws that classed works published abroad before 1973 as “public domain.” The newly amended law complies with Russia’s membership in international copyright conventions; grants retroactive protection to all works for 70 years after the deaths of their author; and allows the full body of Nabokov’s

[4]

work-banned by the Soviet regime until 1986, then chaotically rushed into print-to be re-published with terms and conditions that follow international norms.

Under agreements with the Estate, Azbooka, founded in 1995, will issue uniform editions of Nabokov as novelist, short story writer, poet and memoirist. Lead titles will include Nabokov’s own Russian translation of Lolita; Pale Fire will appear in a Russian translation by Vera Nabokov, made prior to her death in 1991; companion agreements with New York publisher Harcourt, Inc., will add Nabokov’s lectures on literature to the Azbooka list

*****

I wish to express my greatest appreciation to Ms. Paula Courtney for her essential, on-going assistance, for more than 25 years, in the production of this publication.

[5]

NOTES AND BRIEF COMMENTARIES

by Priscilla Meyer

Submissions, in English, should be forwarded to Priscilla Meyer at pmeyer@wesleyan.edu. E-mail submission preferred. If using a PC, please send attachments in .doc format; if by fax send to (860) 685-3465; if by mail, to Russian Department, 215 Fisk Hall, Wesleyan University, Middletown, CT 06459. Deadlines are April 1 and October 1 respectively for the Spring and Fall issues. Most notes will be sent, anonymously, to at least one reader for review. If accepted for publication, the piece may undergo some slight editorial alterations. Please incorporate footnotes within the text. References to Nabokov’s English or Englished works should be made either to the first American (or British) edition or to the Vintage collected series. All Russian quotations must be transliterated and translated. Please observe the style (single-spacing, paragraphing, signature, etc.) used in this section.

“OLD, MAD, GRAY NIJINSKI” IN LOLITA

In the passage dealing with Quilty’s death in Lolita, a reference to the Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinski (1889-1950) visually renders the idea of Quilty’s body rising to an incredible height when hit by Humbert’s merciless bullets: “My next bullet caught him somewhere in the side, and he rose from his chair higher and higher, like old, gray, mad Nijinski, like Old Faithful, like some old nightmare of mine, to a phenomenal altitude, or so it seemed, as he rent the air” (The Annotated Lolita, 302).

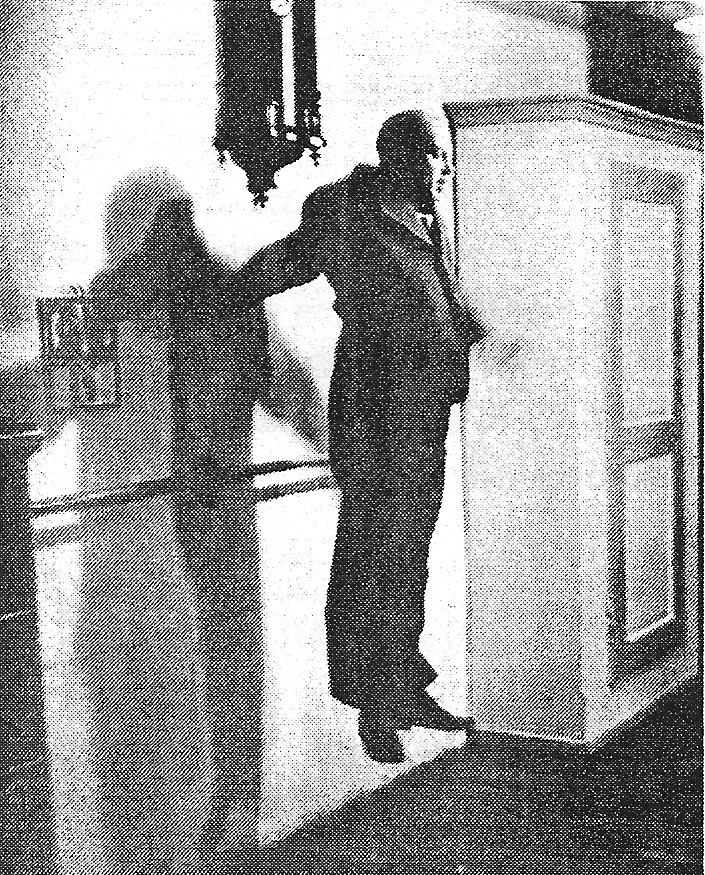

At first sight, this seems to be a general reference to Nijinski’s legendary leaps on stage, but Humbert’s comparison points in fact to a particular photograph of the Russian dancer.

[6]

taken in 1939, when Nijinski was indeed old, gray and mad. After several glorious years as a prodigious dancer in and choreographer of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, when he created the controversial choreographies of The Afternoon of a Faun (1912) and The Rite of Spring (1913), Nijinski started to show signs of mental imbalance, especially after his sentimental break with Diaghilev in 1913. His career soon came to a close and, starting in 1919, he was confined to a series of Swiss hospitals and mountain resorts, under the supervision of psychiatrists and psychoanalysts who were unable to bring him back to sanity.

Humbert’s description refers to a specific episode in June 1939, when Nijinski was staying in the vicinity of Bern with his wife, Romola. Serge Lifar, one of the last major dancers of the Ballets Russes and ballet professor at the Paris Opera, was organizing an exhibition commemorating Diaghilev (who had died exactly ten years earlier, in 1929) at the Pavilion de Marsan (today’s Museum of Decorative Arts) in Paris. Lifar was also

[7]

planning a gala event on the 28th of June 1939 to honour Nijinski and to collect money for his medical treatment. Earlier in June 1939, Lifar visited Nijinski at his hotel near Bern, accompanied by a photographer from the Match review (the ancestor of today’s Paris Match). Lifar’s “heartrending mission” (as the Match journalist put it) was to rekindle Nijinski’s taste for life and his reason by dancing in front of him his own legendary role as the Rose in the ballet The Specter of the Rose (1911). At first, Nijinski was inert and unresponsive, but soon started smiling and examining Lifar’s dancing shoes. Suddenly, when Lifar was on the point of jumping, Nijinski leapt, and the Match photographer managed to immortalize him in mid-air. The photograph, which very probably is the source that gave rise to Humbert’s comment in Lolita, is absolutely spectacular, with the fat old bald dancer in street clothes floating above the ground, his shadow projected against the wall. It strikes one as very similar to the style of German expressionist films, suggesting an expiring soul mounting to heaven, hence the nightmarish impression Humbert records. It is worth noting that in all of Nijinski’s flamboyant dancing career, one leap in particular was to be remembered by posterity as having been supernatural, inhuman in its altitude: it was, interestingly, the leap closing The Specter of the Rose (Martine Kahane, “Avez-vous vu Nijinsky danser?”, Nijinski 1889-1950, exhibition catalogue. Paris. Reunion des musées nationaux, 2000,25).

Vladimir Nabokov probably saw that photograph and read the short article preceding it in the Match review of the 15th of June 1939 (number 50, pp. 44-47). Nabokov was in Paris around mid-June that year, having just returned from a trip to London (Brian Boyd, The Russian Years. Princeton UP, 1990, 508). The article is entitled “Nijinsky” and its subtitle insists on the miraculous moment of the leap, a moment when reason seems to have come back to the dancer: “In the clouded mind of the world’s greatest dancer, a flame lit up for one fleeting second” (translation mine).

[8]

The text is accompanied by nine photographs: the first one presents a young, graceful Nijinski in his petal costume as the Rose in The Specter of the Rose. The following sequence of eight photographs is wholly dedicated to Lifar’s visit. The first seven photographs cover two or three pages, while the last photograph occupies a whole page, presenting the highlight of the article–Nijinski’s leap. The caption under the photograph emphasizes the extraordinary nature of the moment and, consequently, of the image itself: “For the first time in twenty years, dance took possession of Nijinski. A miracle occurs. Nijinski rose in space” (translation mine). The article explains, in the same melodramatic vein: “He fell back to earth, appeased, a smile on his lips. Once more, the small flame had gone out. Вut all those present had the impression that, for one second, Nijinski had been happy” (translation mine).

Nijinski appears twice in Lolita, the first time in Gaston Godin’s “orientally furbished den,” on whose walls one finds a picture of Nijinski “all thighs and fig leaves” (181-182). Susan Elizabeth Sweeney links this reference to Nijinski ’ s famous role as the faun in L’Après-midi d'un faune, insisting on the mythological imagery of nymphs and fauns underlying Humbert ’ s notion of the “nymphet” (Susan Elizabeth Sweeney, “Ballet Attitudes. Nabokov’s Lolita and Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty”, in Ellen Pifer, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. A Casebook. Oxford UP, 2003,121-136). Nijinski emerges episodically in Ada as well, when Pedro performs “a Nurjinski leap” (Ada,199), a composite Nijinski-Nureyev leap. The world and characters of the Ballets Russes are present on Antiterra, where Diaghilev is “ a fat ballet master, Dangleleaf ’ (Ada, 430).

***

A separate but related discussion invites one to link Nijinski’s incredible proficiency as a dancer (especially his ability to jump to stupendous heights) with the theme of gravity in Ada, although no direct textual evidence invites the association.

[9]

However, the Russian dancer’s leaps seem to perfectly match Mascodagama’s obsession with gravity and his attempts at overcoming it. Gravity repeatedly emerges as a major physical obstacle and as a fundamental philosophical problem for a certain number of Nabokovian characters. Van Veen and the narrator of Look at the Harlequins! in particular. Vadim complains of the burden of gravity in terms of unbearable and unavoidable bodily pain: “I still felt Gravity, that infernal and humiliating contribution to our perceptual world, grow into me like a monstrous toenail in stabs and wedges of intolerable pain” (LATH, 85). The alternative to this human submission to the laws of gravity is precisely its denial, which takes a spectacular form in Ada. The fact of defying and defeating gravity is equated in Ada with artistic revelation: “the rapture young Mascodagama derived from overcoming gravity was akin to that of artistic revelation” (A, 185). What Van and Vadim celebrate and what Nijinski seems to have achieved during his meteoric career is precisely the defeat of gravity and the jubilation of flight and dance in the absence of any physical constraints. In Lolita, Quilty’s last leap is actually a leap into death, an act that symbolises perhaps his final defiance of Humbert and of the Humbertian staging of his murder, with the stout satyr floating graciously in the air before plunging into non existence.

—Monica Manolescu, University of Strasbourg

PNIN/PNIN’S SEARCH FOR WHOLENESS

There has been much debate about the art of narration in Pnin, which testifies to how important narrative perspective in novel-writing is, and how conscious of its manipulatory power Nabokov was. So any analysis of the artfully fabricated narration in Pnin is one more example of how we are led to contemplate

[10]

the way all fiction is elegant deception, or “an implicit paradigm for the riddle of consciousness,” that is, “the impossibility of knowing with certainty where the boundary between observed experience and created interpretation falls” as H. Garrett-Goodyear puts it (‘“The Rapture of Endless Approximation”: The Role of the Narrator in Pnin,’ Journal of Narrative Technique, Vol. 16, No. 1,1986,195).

In my opinion, what makes the process of narration in Pnin really effective is the way in which the non-omniscience of the 'rhetorical narrator’ — the man without characteristics—makes Nabokov dramatize the intractability of language to experience, and thus to full comprehension by both the characters within this novel and its readers. First, we acquire full access to Pnin’s personality through the narrator’s skilful handling of the time axis within narration. Whatever the basic story of the novel is, depending on what relation between parts the reader can establish, the narrating voice forces us into adopting the implied time point of paragraph one (October 1950) as the opening of the story sequence as well as that of the text: “The elderly passenger sitting on the north-window side of that inexorably moving railway coach, next to an empty seat and facing two empty ones, was none other than Professor Timofey Pnin” (7, my emphasis).

The deliberate omniscient tone adopted by the narrator at the beginning of his narration is later supported by tense and temporal qualification, compelling us to treat the Pnin of 1950, on the train, as the Pnin of the narrative present. The occurrence of the unexpected adverbial “inexorably” is the only indicator of story temporal sequence in the first paragraph. “Inexorably” implies something already begun, continuing, and impossible to stop or cancel before its own predetermined and unwelcome conclusion: aproleptic announcement of misfortune. The intended foregrounding of meaning is then complicitly “imparted” by the narrator—a deliberate confounder, this time—when he announces in the third paragraph of the novel: “Now a secret

[11]

must be imparted. Professor Pnin was on the wrong train. He was unaware of it, and so was the conductor, already threading his way through the train to Pnin’s coach” (8).

The apparently objective reporting of Pnin’s current, unrecognized error, following a rather lengthy description, in paragraph two, of the hero ’ s appearance, is certainly part of the tactics of confounding the reader about the narrator’s identity. Thus, the various stances revealed by the tone of the teller are felicitously designed to show the significance and impact of two essential components of the narrative: the teller and the tale. While Pnin himself is absorbed in his living experiences, the narrator’s different reactions are directly derived from the equally absorbing spectacle of his character as agent of action. And framing these two is the reader’s bewilderment at the artful telling of the teller’s metamorphosis caused by viewing Pnin’s absorption: a rewarding feeling of togetherness in narration, that Nabokov—the chief-narrator—successfully conveys. Here is one example of how this fascinating carnivalesque performance is put on: “My patient was one of those singular and unfortunate people who regard their heart (‘a hollow, muscular organ,’ according to the gruesome definition in Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary, which Pnin’s orphaned bag contained) with a queasy dread, a nervous repulsion, a sick hate, as if it were some strong slimy untouchable monster that one had to be parasitized with, alas” (18).

Through idiosyncratic features of style, a sense of self-conscious narration is gradually insinuated. This relies on an addressee-based rhetoric, explicable in terms of the reader’s needs and responses. The unusually decelerated description of the obj ect observed, (lengthy parenthetical structures), is followed, one paragraph away, by a shift in time and attitude, expressed by an accelerated description condensing huge spaces in time: “And now, in the park of Whitchurch, Pnin felt what he had felt already on August 10, 1942, and February 15 (his birthday), 1937, and May 18,1929, and July 4,1920-” (18).

[12]

The above-mentioned ellipsis, where a series of detailed scenic presentations are linked by abrupt spatio-temporal jumps, is certainly an exploitation of the temporal discontinuity the modem reader relishes. The result of this spatio-temporal gap or aporia is the reinforcement of the ironic “doctor-patient” relationship referred to in the previous paragraph, which will keep amplifying in the rest of the text. Such variation of tone in the flow of narration will also favor the many stances assumed by the narrator. The subsequent self-conscious narration is nothing but the attribute of both the artificer and the artist, who thus charges discourse with signposts too obvious to be overlooked. The homodiegetic analepses within analepses, some only summaries, others scenes or stretches (“It all happened in a flash but there is no way of rendering it in less than so many consecutive words” 18) belong with a rhetoric of disenchantment through enchantment meant to create that “eerie feeling,” “tingle of unreality” (17) about the character-agent of the action.

Here is another example of how narration handling is a sure source of textual power: “Had I been reading about this mild man, instead of writing about him, I would have preferred him to discover, upon his arrival to Cremona, that his lecture was not this Friday but the next. Actually, however, he not only arrived safely but was in time for dinner- a fruit cocktail, to begin with, mint jelly with anonymous meat course, chocolate syrup with vanilla ice-cream” (22).

The use, in the above-quoted paragraph, of end-weight sentence and internal punctuation gives a more emphatic stress to the situation described by the dramatized narrator, alias dramatized author, who, by now, has well displayed his prowess as text manipulator. To this contributes the abundance of parentheses interlaced with loose paratactic sentences toward achieving an addresser-based rhetoric which cultivates the impression of spontaneity and vigor, usually associated with impromptu speech. All this is part of a carefully orchestrated

[13]

scenario of appropriation of the character-agent of action by the narrator (“our poor friend” soon gives way to “my patient,” and finally, “my Pnin”) within a larger scenario of ventriloquism.

I have dwelled on some rhetorical devices in building the narrating agency in Pnin with a view to discarding, once again, two erroneous assumptions that occur frequently in discussions of the novel. The first is that the novel’s ontology is nothing but a realm of easy omniscience and old- fashioned readerly comfort, which, fortunately, M. Wood, among others, ably demolishes (The Magician’s Doubts. Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction, London: Pimlico Edition, 1995,157-172).The second supposition is that the narrator is none other than a textual version of Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov, which Brian Boyd also dismisses (Vladimir Nabokov, The American Years, Princeton University Press, 1991,271-286).

The juxtaposition of the rhetorical narrator’s aesthetic prowess (not free of potential ambiguities) and Pnin’s ‘aesthetic for life’s sake’ (not unlike Nabokov’s own ‘aesthetic for life’s sake’) partakes of the technique of the sumbolon (a Greek symbol, representing an instrument of power and its exercise whereby a person who holds some secret or power breaks some ceramic object in half, keeping one part and entrusting the other to an individual who is to carry the message or certify its authenticity), with which M. Foucault associates Sophocles’ Oedipus, due to the story’s emphasis on the many nested halves to fit together (“Truth and Juridical Forms,” Essential Works of Foucault 1954-1984. Vol. 3, Power, ed. by J. Faubion, trans. R.Hurley and Others, Penguin Books, 2002,1-87). This is to say that the narrative dis/play is a way of shifting the enunciation of the truth from a prophetic perspective type of discourse (the narrator’s deliberately obliterative stances) to a retrospective one (the character-protagonist’s stance) that is no longer characterized by prophesy but, rather, by evidence. Pnin’s way of authenticating his past and beliefs is found in Victor, son of his former wife, who cherishes the same dreams/

[14]

art ideals/ fears as himself. The act of having the resplendent glass bowl (received from Victor as a token of his love/ admiration/ respect), at once jeopardized and saved intact, at the end of the novel, is an allegory of the ‘sumbolon’ principle, whereby Pnin, the ‘ideal’ Russian in America, (as laughable, as pitiable), joins forces with Pnin––the ‘Victor,’ who abides by principles of innate honesty, thus eluding prophecy. This doesn’t mean that Pnin, the recovered complete ego, can elude the author with his subtle awareness of fiction’s boundaries.

At the very end of the novel, Pnin’s sedan, “free at last,” vanishes up a “shining road, which one could make out narrowing to a thread of gold in the soft mist where hill after hill made beauty of distance, and where there was simply no saying what miracle might happen” (160). This might well be the landscape of fairyland, that is, of magic/ imagination/ fiction, Nabokov ‘Sole Owner and Proprietor.’ So, time and again, Nabokov leads the way to tracing the boundaries of what fiction can depict, but mostly, showing the splendor of what it can imply— the kind of deep bow the writer would always make to his favorite readers, “Reader! Bruder!” (Lolita, 262).

—Maria-Ruxanda Bontila, University of Galati

WHAT TROUBLED CHEKALINSKY ?

In his “Translator’s Notes I” (first published in the Russian-language émigré New Review in 1957, Book 49) Vladimir Nabokov takes the Gentle Reader to task for being too inattentive to details in classic Russian literature. Nabokov lists a few instances from Lermontov, Tolstoy, and Pushkin, where the authors appear to have hidden an allusion or a clue leading to a certain interpretation and where the reader has often stumbled and then passed on simply ignoring a telling detail or a subtext. Among the examples cited by Nabokov only one seems

[15]

unidentified: neither the 1997 anthology V.V. Nabokov: Pro et contra, where “Translator’s Notes” (I &II) were published, nor the definitive and most up-to-date Symposium edition of Nabokov’s Russian works (2003) provide commentary to this crux. The Pro et contra anthology simply states that “it is unclear what cause of Chekalinsky’s embarrassment Nabokov had in mind” (p. 889), while the Symposium edition just quotes the pertaining passage in Pushkin’s “The Queen of Spades” without any commentary (Sobr. soch. russkogo perioda, vol. 5, p.797).

Here is the text in Nabokov’s “Notes”: “Dusty tomes have been written about some ‘superfluous people’, but who of the intelligent Russians took the trouble to find out what the4 Young France’ mentioned by Pechorin is, or what it was that ‘disconcerted’ the worldly-wise Chekalinsky so much?” (Sobr. soch. russkogo perioda, vol. 5, p. 604, my translation).

The question is: why was the worldly-wise Chekalinsky so disconcerted? The question refers to the last chapter of Pushkin’s “The Queen of Spades”, where Hermann, the protagonist possessing the secret of the three cards is winning enormous sums of money in the game of pharo (the banking game, according to Nabokov’s commentary to Eugene Onegin, vol. 2, p. 259). The experienced Chekalinsky deals in this game and is Hermann’s only adversary. Indeed, we know that Chekalinsky has been around card tables quite a lot and, we should assume, has seen people win such sums (Hermann’s final stake is some 188,000 rubles and so he should win about 376,000). Nevertheless, the first magical winning by Hermann made him frown (“Chekalinsky frowned, but instantly the smile returned to his face”, Gillon R. Aitken’s 1978 translation, p. 304), the second put him out of countenance, and in the expectation of the third magical winning the dealer’s face becomes pale and his hands shake. What was he so preoccupied about?

Pushkin uses a very short sentence, without going into any further psychological detail, to describe Chekalinsky’s external

[16]

features after Hermann’s second winning: “Chekalinsky was clearly disconcerted” (Aitken, p. 304; in Russian,“Chekalinsky vidimo smutilsya”, in: Pushkin, Sobr. soch. in 10 vol., vol. 5,p. 261, lit. “was visibly disconcerted”). It is significant that Pushkin already used this expression in the same story: “the Countess was visibly disconcerted” (Aitken, p. 293, “Grafinya vidimo smutilas’” in: Pushkin, op. cit., p. 249). The context for that earlier occasion is as follows: Hermann, obsessed with the idea of getting the secret of the three winning cards from the old Countess and thus ensuring his win in the game of chance, is anxious to make her reveal it to him. The Countess dismisses it as a joke. Hermann then mentions the rumor according to which years ago she already revealed the secret to another man, Chaplitsky, which enabled him to win back the lost 300,000 and more from Zorich, the famous gambler and one of the favorites of Catherine the Great. This puts the Countess out of countenance. The reader and Hermann learn the story of Chaplitsky and Zorich from the Countess’s grandson in the beginning of the narrative.

The beginning of Chapter 6 describes Chekalinsky as a gambler who has spent his entire life playing cards. The fact that he is an experienced old player is emphasized: we learn that he is of about sixty years of age. So we can assume he was present at some important games in his youth or heard something about them. And the game between Chaplitsky and Zorich must have been rather important, at least the magical luck of Chaplitsky as he won the 300,000 back from Zorich with just three cards must have caused quite a flurry of rumors in the gamblers’ circles, and the young Chekalinsky belonged to those circles.

The conclusion which we can draw from this textual association of the two episodes is that Chekalinsky knew the story about Zorich and Chaplitsky, and, given his life-long passionate interest in cards, may have even known the secret combination of the winning cards. And as he saw a young man staking large sums of money and then invariably winning with

[17]

the already familiar combination of cards, he was understandably afraid that history repeats itself and that this time it is he who is going to lose a fortune. When he saw the trey win, he frowned and probably shrugged it off as a coincidence. But the second win of the seven disconcerted him, put him out of countenance. And waiting for the final third win of the ace, he was pale and his hands were shaking. But when that didn’t happen, he was smiling again.

The similarity of the names Chaplitsky and Chekalinsky supports this interpretation: even though their respective roles are opposite in these two different games, they share the secret knowledge of the three winning cards (along with Hermann). Besides, the sums Chaplitsky and Hermann won are comparable: Chaplitsky’s first stake is 50,000,Hermann’s 47,000: in the end, Chaplitsky won 400,000 rubles, Hermann could have won 376,000, if he hadn’t “obdernulsya” (“slipped up” in Aitken, p. 305; “mispulled,” “misdrew” the wrong card from the deck, according to Nabokov’s commentary to Eugene Onegin, vol. 2, p.259).

The most obvious objection to this interpretation can be summed up by the question: why Chekalinsky, knowing the secret combination of the cards, did not use this knowledge to enrich himself. The answer to this question is also simple: 1) he was already rich and had amassed millions by winning at cards, and, most importantIу, 2) the unavoidable condition which came along with the revealing of the secret combination of cards to both Chaplitsky and Hermann was that they should never play again. This condition was apparently too much for such an inveterate gambler as Chekalinsky, and even knowing the most coveted secret in the world of gambling, he never capitalized on his knowledge, because it meant he could never indulge his passion again after that.

Now it seems clear what “disconcerted” Chekalinsky so much: he recognized the sequence of the winning cards that Hermann played. Nabokov noticed it, or that is how he interpreted

[18]

the textual hints in the story. He then in his turn hinted at this possible interpretation in “Translator’s Notes” by posing his question without, however, putting forth his reading explicitly. This is an attempt to answer that question: to retrace Nabokov’s steps in reading Pushkin’s story.

— Sergey Karpukhin, University of Virginia

REMBRANDT’S DEPOSITION FROM THE CROSS IN THE GIFT

Rembrandt, the quatercentenary of whose birth is celebrated this year, and his art are frequently referred or alluded to in Nabokov’s works. For example, King, Queen, Knave contains references to “the air of Rembrandt” and “the brightest Rembrandtesque gleam” (KQK 91 and 154) and “The Visit to the Museum,” similarly, to “a copper helmet with a Rembrandtesque gleam” (Stories 282). The latter phrase brings to mind such paintings by or attributed to Rembrandt as The Man with the Golden Helmet (ca. 1650, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin); Mars (1655, Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow), and its assumed pendant Pallas Athena (1663, until 1930 in the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg; presently in the Museu Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon)—the latter two also each known as Alexander the Great. And in Ada, Nabokov metaphorically and most succinctly conveys the essence of Rembrandt’s art that outweighs many volumes written on the illustrious Dutchman: “Remembrance, like Rembrandt, is dark but festive” (Ada 109).

In addition to these generic references that suggest Rembrandt’s predilection for the interplay of light and shadow as well as the spirituality of his celebratory art, Nabokov points to specific works by the Dutch master. Thus, Rembrandt’s Christ at Emmaus, also known as The Pilgrims at Emmaus, or

[19]

Supper at Emmaus (1648, Musée du Louvre, Paris), is mentioned in Pnin. In this novel, a “reproduction of the head of Christ” from this painting, “with the same, though slightly less celestial, expression of eyes and mouth” (Pnin 95), hangs in the studio of Lake, Victor’s art teacher. Twenty years earlier, Nabokov alluded to Christ’s countenance in this painting in the description of Cincinnatus’s face when speaking of “the light outline of his lips, seemingly not quite fully drawn but touched by a master of masters” and “the dispersing and again gathering rays in his animated eyes” (IB 121).

Another reference to a particular work of Rembrandt can be found in The Gift. In his Life of Chernyshevski, Fedor Godunov-Cherdyntsev, the protagonist and narrator of the novel, sarcastically notes that biographers viewed the author of What Is To Be Done as “Christ the Second” and

mark[ed] his thorny path with evangelical signposts /.

. . ./ Chernyshevski’s passions began when he reached Christ’s age.

Here the role of Judas was filled by Vsevolod Kostomarov; the role of

Peter by the famous poet Nekrasov, who declined to visit the jailed man.

Corpulent Herzen, ensconced in London, called Chernyshevski’s pillory

column “The companion piece of the Cross.” And in a famous Nekrasov

iambic there was more about the Crucifixion, about the fact that Chernyshevski

had been “sent to remind the earthly kings of Christ.” Finally, when he was

completely dead and they were washing his body, that thinness, that steepness

of the ribs, that dark pallor of the skin and those long toes vaguely reminded one

of his intimates of “The Removal from the Cross”—by Rembrandt, is it?

(Gift 215; italics are Nabokov’s)

While, as the passage indicates, Fyodor is not quite certain who painted the canvas in question, Nabokov, the true creator of the novel, is fully aware of Rembrandt’s authorship and

[20]

employs the “by Rembrandt, is it?” phrase as an emphatic, attention-drawing device.

There are at least five versions of Rembrandt’s The Deposition [Descent] from the Cross to which Fyodor hesitantly refers here: three paintings, one located at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, the other at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg (both date from 1634), and the third at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC (ca. 1651), and two etchings (1633) (Fig. 1) and The Descent from the Cross by Torchlight (1654). Knowing Nabokov’s penchant for the authorial presence, it is most likely that he had the earlier etching in mind—the only variant that contains a person evidently bearing the artist’s easily recognizable features. It is of course the individual standing on the ladder and supporting Christ’s left arm. To Nabokov’s choice points the phrase “those long toes,” which look more prominent in the etching. This assertion is also validated by the novel’s description of the work of art as depicting “dark pallor of the skin” and “steepness of the ribs” that appear more pronounced in the etching in which the body of Jesus is lit with somewhat dim and suffused backlighting. In the paintings, on the other hand, the body of Christ is shown in brighter light and therefore does not give this impression. The later etching does not match Nabokov’s description either, since “steepness of the ribs” is obscured by one of the individuals lowering the corpse of Jesus.

Nabokov’s mention of Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross, presumably the earlier etching, most likely implies the writer’s authorial presence in the novel. Furthermore, when referring to The Deposition from the Cross, Nabokov apparently also intended to invoke The Raising of the Cross (1633, Alte Pinakothek, Munich), to which the earlier version of The Deposition from the Cross served as the pendant (Fig. 2). In The Raising of the Cross, Rembrandt portrayed himself once again, but this time as the soldier who helps to lift the cross, to which the body of Jesus is nailed. (Rembrandt painted both

[21]

works as part of the Passion series for Prince Frederick Henry of Orange.) By juxtaposing these two pieces in which Rembrandt assigned such diametrically opposing roles to his own image, one may conclude that the artist, in all likelihood, wished to convey the message of collective human guilt, including his own, for the death of Jesus. At the same time, he evidently wished to show penitence when depicting himself as the sorrowful figure, in anguish, that helps lower Christ’s corpse from the Cross. By mentioning Rembrandt’s Deposition from the Cross and by invoking his Raising of the Cross, Nabokov seems to suggest a more humane role for his protagonist who is credited with the authorship of the novel about Chemyshevski’s life.

Earlier in The Gift, Nabokov teaches Fyodor a lesson against stereotyping. Upon riding a tram, Fyodor is seized with prejudice against Germans, even though it was, “he knew, a conviction unworthy of an artist” (Gift 80). When another passenger boards the tram, Fyodor directs his hostile thoughts toward this man, discovering his more and more unattractive, “typically German,” features. While Fyodor “threaded the points of his biased indictment, looking at the man who sat opposite him,” all of a sudden, the fellow passenger took a copy of the Russian émigré newspaper from his pocket “and coughed unconcernedly with a Russian intonation” (Gift 82). Fyodor fully comprehends the message that life, or better to say, his creator sends him: “That’s wonderful, thought Fyodor, almost smiling with delight. How clever, how gracefully sly and how essentially good life is!” (ibid.). This earlier ethical lesson prepares Fyodor for a more complex and benevolent perception of the world, so important not only in his task of writing the Chemyshevski biography but also “the autobiography,” something he will be “a long time preparing” (Gift 364).

The reference and allusion to Rembrandt’s two Biblical pieces shed light on Fyodor’s, and Nabokov’s own, dual approach to “Christ the Second”: on the one hand, the protagonist

[22]

exhibits disdain toward Nikolai Chernyshevski (1828-89), a philosopher, writer, and aesthetician; and on the other, he demonstrates compassion when admiring Chernyshevski’s personal courage and the steadfastness of his beliefs. Thus, Fyodor “began to comprehend by degrees that such uncompromising radicals as Chernyshevski, with all their ludicrous and ghastly blunders, were, no matter how you looked at it, real heroes in their struggle with the governmental order of things” (Gift 202-3). This dual approach clearly reflects Nabokov’s own attitude toward Chernyshevski, “whose works,” as he puts it, “I found risible, but whose fate moved me more strongly than did Gogol’s” (SO 156). Nabokov, the creator of both Fyodor and Chernyshevski, warns against pigeonholing and a superficial, schematic approach to life, which Fyodor, his alterish ego, learns to recognize. In so doing, the writer advocates “mercy toward the downfallen” (EO, 2:311) in the compassionate tradition of Pushkin, whom he revered, and in accordance with the best liberal convictions of his own family. In the spirit of Rembrandt’s Passion masterpieces, Nabokov teaches the reader to be more benevolent and to seek redeeming features in every fellow human, no matter how “risible” the person may appear.

—Gavriel Shapiro, Cornell University

PAINTING AND PUNNING: CYNTHIA’S AND SYBIL’S INFLUENCE IN “THE VANE SISTERS”

While the plot of Vladimir Nabokov’s “The Vane Sisters” (1951/59) may seem a simple one, about the unnamed narrator’s peculiar reaction to Cynthia Vane’s death, this work is complicated by its word play, its unreliable narrator, and its many allusions-most of which David Eggenschwiler has explicated in his article “Nabokov’s ‘The Vane Sisters’: Exuberant Pedantry and a Biter Bit” (Studies in Short Fiction,

[23]

1981, 18.1: 33-39). The professor of French literature who narrates “The Vane Sisters” presents the two siblings, Cynthia and Sybil, as rather hapless, high-strung creatures, and while he recognizes Cynthia’s “artistic gift” of painting, he refuses to see Sybil as a creative person, only as the relatively inconvenient lover of fellow professor D. (Nabokov, “Vane Sisters” Stories of Vladimir Nabokov, Vintage, 1997: 624). Despite the narrator’s attempts to dismiss the Vane sisters because they inhabit a world of auras and emotion outside his scholarly, intellectual domain, their artistic influence runs throughout his narrative, particularly in the symbolic colors of each sister’s characterization.

The first section of “The Vane Sisters” obviously connects to the acrostic ending: “Icicles by Cynthia; meter from me, Sybil” (631) in that, on his “usual afternoon stroll,” the narrator becomes transfixed looking at “a family of brilliant icicles drip-dripping from the eaves of a frame house.” This icicle “family” also leads him to notice a certain “rhythm,” or meter, in the dripping as each sister contributes to the painterly scene before him and immediately reveals her artistic influence, her own way of coloring the narrative. The Vane sisters, particularly Cynthia, send him on his own “series of’ what he considers “trivial investigations” that actually constitute an artistic quest of sorts, a search for the “shadows of the falling drops” from the melting icicles. Furthermore, the grey of the “pointed shadows” and the “blue silhouettes” of the icicles form specific color associations with the sisters. Both Cynthia and Sybil are connected to shadows and shade, especially Sybil whose grey shadow seems to haunt the narrative. Cynthia is also linked to or represented by the color blue, so the narrator’s particular attention to detail and to color throughout the narrative is a reflection of one or both of the sisters. Thus, under their influence, the narrator finds himself with an uncharacteristically “sharpened ... appetite for other tidbits of light and shade” (619).

[24]

Although Cynthia and Sybil cannot definitely be said to possess the “colored hearing” or synesthesia that Nabokov describes himself as having in Speak, Memory (Vintage, 1989: 34), they are akin to Nabokov in their awareness of color as they speak to the narrator through their shades of blue and grey. For example, Nabokov claims that “[s]ince a subtle interaction exists between sound and shape,” he sees “q as browner than k, while s is not the light blue of c, but a curious mixture of azure and mother-of-pearl” (35). Nabokov’s “colors” for s and c in this passage are significant as a link to the colors of Sybil and Cynthia in “The Vane Sisters” and to the sibilant sounds of their names, sounds echoed in the Russian term for blue-grey iridescent—sizyi. Each sister’s name has additional meaning in the text, as the name Sybil originates with the Sibyl of Cumae, a Greek prophetess and “woman of deep wisdom, who could foretell the future” and served as guide to Aeneas on his journey into the underworld (Edith Hamilton, Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes, Mentor, 1969: 226). This name is particularly fitting to grey Sybil Vane, who speaks to the narrator in the portentous acrostic as a way to guide him on his day’s journey and in understanding the hereafter. The name Cynthia is one of the names of the Greek goddess of the moon and the hunt, Artemis; the name Cynthia comes “from her birthplace, Mount Cynthus in Delos” (31). Cynthia Vane, already associated with the color blue, is further connected by her name to the metallic, silvery colors of reflection and images of the moon and night.

As the narrator unknowingly travels through the sisters’ “intervenient auras,” much of his story presents clearer characterizations of Cynthia and Sybil than of himself (Nabokov, “Vane” 624). Cynthia’s aura leads the narrator, through “peacocked lashes” (619), to appreciate the “vivid pictorial sense” of his surroundings, particularly in relation to his favorite painting by Cynthia, a winter scene entitled Seen Through a Windshield (620). As he walks along, the wet winter landscape

[25]

lies stretched out before him like one of Cynthia’s freshly painted canvases. The narrator admires Cynthia’s “wonderfully detailed images of metallic things” in her artwork (624); therefore, on his Sunday walk, he notices “for the first time the humble fluting... ornamenting a garbage can” and “the rippling upon its lid” along with “the dazzling diamond reflection of the low sun on the round back of a parked automobile” (620,619). In Cynthia’s Seen Through a Windshield, “the sapphire flame of the sky” sparkles through the frost (624), connecting to the “blue silhouettes” of the icicles (619) and the “neon blue” that the narrator would like to see instead of “the tawny red light of the restaurant sign” where he ends his peripatetic day (620). The “green-and-white fir tree” (624) in this painting connects to the beginning of the narrator’s journey as he looks at the “white boards” of a house to watch the icicles, which lead him to Kelly (green) Road and then “to the house where D. used to live” (619). Cynthia’s guiding hand, which created the “honest and poetical pictures” the narrator admires, appropriately leads him to appreciate the splendor of this wintry day and, eventually, to the discovery of her death (624).

Cynthia’s association with water throughout the story is twofold: first, in her role as an artist, a creator of watercolors (her paintings are not “straight” but fluid), and second, in her beliefs, her view of life as a watercolor of auras, a blend of this world and the next (625). Along with the icicles and their droplets, Cynthia is connected to the water of the thaw (620), the “sacred river” she discovers in a poem (626), and the “cloudburst” of “sparse rain” during her argument with the narrator (628-29). Her sorrow after Sybil’s suicide is another link between Cynthia and water, as she splashes “soda water and tears” onto Sybil’s notebook (622). Cynthia even takes a “‘cold water’ flat” in New York City (623), reminiscent of Sybil’s “chilly little bedroom” (622) after her sister’s death. Cynthia finds comfort from her grief, however, in her belief that life is influenced by the deceased: ‘“a usual day’ might be itself

[26]

a weak solution of mixed auras,” a combination of colors that would occasionally “stand out in relief’ and then begin “shading off . . . as the aura gradually faded” (625). This aesthetic depiction of daily 1 ife explains why Cynthia chooses to speak to the narrator through the icicles and blue tints of winter. To her, life, art, and death are interconnected, and to make the narrator feel her presence after her death, she must reveal the beauty she captured, through her art, in life.

Despite the narrator’s remembering the beauty of Cynthia’s artworks, he is often unflattering in his description of her or her surroundings. For example, while he does think of Cynthia as “a painter of glass-bright minutiae” (631), he also thinks of the “black hairs that showed all along her pale shins through the nylon of her stockings” as looking like a “scientific . . . preparation flattened under glass” (623). With this observation, the narrator seems to be mocking Cynthia, derisively implying she is a “bluestocking.” He also ridicules the parties, “grouped within a smoke-blue space between two mirrors gorged with reflections” (628 emphasis added), that Cynthia holds at her neighbor’s apartment because “her own living room always looked like a dirty old palette” (627). He describes the festivities at the Wheelers’ flat in a combination of “pale carpet,” a “pearl-gray sofa,” and “glasses that grew like mushrooms in the shade of chairs” (628). In cataloging these surroundings, the narrator inadvertently makes Cynthia’s parties seem natural, a mixture of earthy items and colorful people-including watery, blue Cynthia herself who sits “like a stranded mermaid” and a “woman in green” who “had written a national best-seller in 1932” (628, 629). Moreover, the references to reflective surfaces here—the glass, water, and metal objects the narrator notices—are part of Cynthia’s influence on the narrator as she reminds him not just of her paintings, which reflect her environment, but of her life.

Cynthia’s life is full of color, which the narrator’s own existence seems to lack without her, from her “amber umbrella”

[27]

(628) to the mар she marks to remind D. of the “pink and brown forest” near a motel where he and Sybil once stopped (624). Even Cynthia’s friend, Betty Brown, “a decrepit colored woman,” is part of the color scheme of Cynthia’s life (625 emphasis added), but her name also seems to be one of Sybil’s puns: a “brown betty either the traditional dessert or literally a “brown” woman named “betty,” is reversed to form a colorful proper name. All of these colors-shades of blue, grey, brown, pink, amber, green, and white-in Cynthia’s life serve as Nabokov’s clues to her role in the narrator’s life and to her artistry outside the narrator’s perspective.

While Cynthia attempts to make her presence known to the narrator mostly through scenic aspects, Sybil, whom the narrator characterizes as speaking through a “prism” of “wild talk” about D.’s wife,relies on language as well as color to reveal her own influence (621). Sybil’s shadow first appears along with Cynthia’s icicles in the “twinned twinkle” of shadow and droplet (619). However, the word icicle here is also a pun, used in a similar manner in Pale Fire with Kinbote’s “Institute for the Criminal Insane, ici" (Vintage, 1989: 295), telling the narrator and the reader that the icicles are the “key” to solving one of the puzzles within “The Vane Sisters”: “If we divide the word ‘icicles’ in two, we realize that it consists of two French words, ici and cles. It sounds as if Nabokov were saying to the reader: ‘Here are the keys’” (Seiji Kurata, “Icicles in ‘The Vane Sisters,”’ Nabokovian, 1998, 40: 14). The word play here prepares the reader for Sybil’s punning in her suicide note and is another way for her to provide a clue for her identity. Furthermore, at the end of section one, in another of Sybil’s word games, D., on his way from Albany to Boston, tells the narrator of Cynthia’s death, of her joining Sybil in “Elysium” (Nabokov, “Vane” 622), an alphabetical journey–A, В, C, D, E–that reminds the reader, if not the narrator, of the narrator’s “having arranged the ugly copybooks alphabetically” and finding that Sybil’s exam has been “somehow misplaced.” Sybil provides

[28]

the meter, or rhythm, of the narrative through a succession of linked people and places in her life, reminding the reader how she herself has been “somehow misplaced” in the lives of D. and the narrator.

One of Sybil’s more subtle ways of communicating with the narrator is in his depiction of her last day in his French class, which is marked by sibilance, a reminder of both her own name and her sister’s:

I remember sitting next day at my raised desk in the large classroom

where a midyear examination in French Lit. was being held on the eve

of Sybil’s suicide, She came in on high heels, with a suitcase, dumped it

in a corner where several other bags were stacked, with a single shrug

slipped her fur coat off her thin shoulders ... and with two or three other

girls stopped before my desk to ask when I would mail them their grades,

(emphasis added)

Even though he views Sybil as “childishly slight” in form and in mind (621), she seems to echo in the narrator’s memory, as this moment in the text is a synesthesetic mix of sounds, colors, and images that allows her to speak to him in his recollection of it.

Through moments such as this, Sybil becomes a sympathetic character who seems lonely and misunderstood. In the acrostic of the narrator’s dream, “meter from me, Sybil,’’Sybil alerts the reader that she can be found in the “lean ghost, the elongated umbra cast by a parking meter.” Her “metered” shadow is tinted with the “red light of the restaurant sign,” the light the narrator wants to find in “neon blue” because he would rather remember Cynthia than the tragic, suicidal Sybil (620). The mixture of grey and red is another reminder of Sybil’s last day in the narrator’s French literature class as the narrator notices her “cherry-red chapped lips” and her clothes of “close-fitting gray” (621). This shading continues in Sybil’s exam with various hues of pencil grey: “She had begun in very pale, very

[29]

hard pencil” and “continued in another, darker lead, gradually lapsing into the blurred thickness of what looked almost like charcoal, to which, by sucking the blunt point, she had contributed some traces of lipstick,” final ly ending her note with a borrowed fountain pen like the “diluted blue ink of her eyes” (621-22). While Cynthia sees Sybil’s personality as having a “rainbow edge as if a little out of focus” (625), the narrator discusses Sybil in terms of various shades of grey and red, shadows with a “ruddy tinge” (620), and even though Cynthia wants to “disarm [Sybil’s] shade” (624), the narrator only sees “the chance that mimics choice” in the incidents that Cynthia attributes to Sybil after her suicide (626). The narrator continues to consider Sybil only in terms of her relationship with D. and as Cynthia’s younger sister; thus, Sybil must provide her own characterization for the reader.

The narrator’s “vague” dream at the end of the story, “yellow-clouded” and “yellowly blurred” by the sun coming “through the tawny window shades” of his room, actually provides, with Sybil’s acrostic, the end of his day’s quest, his search for what lay behind the icicle droplets he observed earlier (631). The colored language in the narrator’s final words of the story also “indicat[es] both [Cynthia’s and Sybil’s] continuing presence and the nature of their intervention in his life” (Michael Wood, The Magician's Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction, Princeton UP, 1994: 75). The hypersensitivity the narrator displays during his transformation into “one big eyeball rolling in the world’s socket” gives him a new vision, a new awareness, but ultimately this gift of sensitivity is Cynthia’s and Sybil’s “coin trick” from beyond the grave (Nabokov, “Vane” 619), each toying with him like a “stray kitten” and allowing him to see his surroundings through her eyes (624).

Regardless of the narrator’s decision to “refute and defeat the possible persistence of discarnate life,” Cynthia and Sybil still communicate with him, however silently, through their

[30]

shading, tinting, and arranging (630). Because the narrator attempts to keep the Vane sisters on the margins of his life, he is unaware of the choices, in the guise of coincidence, that both Cynthia and Sybil make for him on his Sunday. His efforts fail, however, as they, from the exile of death, influence him in ways they could not when they were alive. While the narrator comes to recognize the “two kinds of darkness,” that of “the darkness of absence and the darkness of sleep,” he does not appreciate the Vane sisters’ efforts in utilizing both light and dark, luminosity and shade, to reach him (629) .Although they do not provide the narrator with a “cheap poltergeist show,” the Vane sisters definitely, but subtly, direct the course of the narrator’s day and reveal their personalities to the reader through their artistic creativity (630).

—Misty Hickson Reynolds, University of Georgia

GRADUS AMORIS

At Cambridge, Vladimir Nabokov devoted his studies to both his native Russian literature, and French literature, with the result that a serious reader of especially his later works immediately understands how they partake of the richness of each of these literatures. The serious and informed reader must have a founding in them both, as well as in the “greats” of Anglophone books. Boyd, in dealing with Nabokov’s “Russian Years,” then states that, “In all his formal studies at Cambridge, Nabokov’s greatest gain was probably the deep love he acquired for the [French] medieval (my emphasis, J. А Rеа) masterpieces he may not otherwise have encountered...that could share a shelf in his mind” (176). Yet although much has been written about the contributions of Russian and modern French works, precious little has dealt with any similar contribution from

[31]

Nabokov’s familiarity with medieval French. A medievalist becomes soon aware of this neglected treasure.

The gradus amoris (“stairway of love,” also called scala amoris) is a convention used by medieval writers to specify and make concrete the stages, or “steps,” in the progress of love. These were typically visus, alloquium, contactus, osculum and factum: first, seeing the “prize,” then conversing, then physical contact, then kissing, and finally the “act” (also known as “id”); or as Chaucer puts it in “The Parson’s Tale” (11 853-54), “lookynge, wordes, touchynge, kissynge,” and, “the dede.” (Lionel Friedman in R. Phil. 19: 167-77,1965 gives useful background on this topos.) In Ada, Nabokov not only uses this device, but plays complex variations on it, as he often does with conventions, frequently by first trivializing or undercutting each of these “stages,” then by a crescendo of embellishments of each, all the while calling our attention to the “stair” motif by literalizing it, by giving us material stairs and steps. One of the latest online reference aids, Wikipedia, to date has no entry for either “Gradus Amoris” or its alternate “Scala Amoris.” But its more mature elder cousin, Google has a plethora of helpful references.

Just after his arrival at Ardis, Van recognizes in the garden, “his former French governess. ...reading aloud to a small girl who... .must be “Ardelia” (p 36 lines 21-27), (i.e., Ada) the elder of the two little cousins he was supposed to get acquainted with.” It is not, in fact, Ada, but rather her half sister Lucette. Thereby this initial visus. Van’s first sight of Ada, has been sabotaged by undercutting, by his mistake. Subsequently, Van first sees the real Ada, at the front porch of Ardis, descending from a Victoria (the first two actual steps which Nabokov will associate literally with stages of the gradus) accompanied by Marina and a dachshund, which we shall soon come to know. Nothing immediately seems to ensue from this first sighting, however, and the narrative cuts to the main hall of Ardis,

[32]

starting at the “grand staircase” (of course!), from which Ada will lead Van on a “guided tour” of the country house.

Nabokov then expands and embellishes on this visus motif when, during that guided tour, pantiless Ada subsequently precedes Van by three steps up a “semi-secret little” spiral staircase (still calling attention literally to the “stair” nature of the gradus amoris) whereby he is now treated to the sight of her “pale thighs.” Then on their second trip upstairs Ada’s skirt is “wrenched up,” after she climbs on a trunk, enabling Van to see “that the child is darkly flossed.” (Looking ahead, we note that a similar view is probably seen, with perhaps more, as she dances a pantiless “fling” in her wide hemmed Gipsy skirt; and even more clearly as she climbs above him in the shattal tree where Van is “not...able to see her face,” (94:11), to which we shall return shortly. A further progression in this visus theme occurs when Van sees even more of Ada, nude from the waist up, as she washes. Later Van peers down the loose back of Ada’s dress “as far as her coccyx” (99:26-44). And of course it is not only the stairs that receive verbal emphasis. In just a handful of lines, for instance, starting on page 5 9 we can snip out the following bits: the glimpse (line 22) of her he had; and he saw (27) as one sees (27) some ...miracle; He noticed (29); that she seemed to have noticed (30) that he ... might have noticed (30) what he not only noticed (31); he freed himself from that vision (33); dull arrogant look (33). And “he... had been a blind virgin” (p. 60 lines 3-4). I might comment on this patch of visual vocabulary as “Out of sight!” The full view of her body appears on the night of the “burning barn,” of course, when Van (who had come down the stairs to behold the conflagration) helps Ada out of her wet “nightie” (pp. 120:25-26). Stages within a stage of this veritable “spogliarello.”

The first alloquium takes place appropriately at the foot of the grand stairway (37:30-2) in Ardis, where Van and Marina are chatting, and Ada so far is a silent third .This initial utterance consists of Ada’s minimal, “Pah,” (38:21), but in response to a

[33]

comment by Marina, and not to Van, who has yet to address Ada (and it is followed at 39:12-13 by a whispered utterance to a dog!). When, at Marina ’ s suggestion, Ada leads Van on a tour of the house, the continuous hectic upstairs and downstairs shuttling (especially pp 42-45) again instantiating physically the stairs topos, is accompanied by Ada’s deluging Van with a voluble monologue of ciceronic commentary, in the long, rambling, sentences so typical of her style. (Curiously, this detailed, commentated tour of Ardis eschews quotation marks, and could well be the voice of a “narrator”— whoever that might be). Overwhelmed with this description of architecture, furnishings, family members and decor, Van finally says, but to himself, not even aloud, “I’m going to scream” (41:21). The alloquium stage having thus been undercut, Ada’s very first (ambiguous?), personal, quoted words to Van in the novel are “You have not seen anything yet....” (45:11), perhaps reminding us of “Thou hast seen nothing yet,” in Don Quixote (III ii p 30) or the more colloquial, “You ain’t seen nothin’ yet.” Van’s subsequent first (ambiguous?) actual words to Ada in response to Ada’s indication that they will next see the roof, are, “But that is going to be our last climb of today” (45,13). Not too promising as an opening conversation of these lovers-to-be, whose first real chat on page 50, and who are soon to be engaged in a frenzied verbal tennis match involving Rimbaud’s poem (63:4-66), and a most intimate exchange that demonstrates another nice bit of gamesmanship. (We shall not pause over any doubles entendres present in “climb” and in “go upstairs” -familiar in bawdy house parlance.)

Their first physical contact occurs at 50:7-8, when Ada takes Van’s hand in response to Mile Lariviere’s suggestion (just before their first personal chat beginning on that page at line 15). And note that Ada initiates this hand holding, too, just as she had spoken to Van before he did to her, and as she,rather than, Van often initiates events. But this first contact by handholding has, in fact, been undercut by a much more trivial

[34]

contact when (on 39:26) Ada’s hair touches Van’s neck. (And a much more significant contactus subsequently ensues after the picnic when pantiless Ada rides home on Van’s lap at 86:13-14.) And, of course a still more intimate contact results from Ada’s “fortunate fall” in the Shattal tree, bringing her crotch into contact with Van’s face, at 94:18. And the first intentional sexual contact comes when her, “index traced the blue Nile (the vein of Van’s penis) down into its jungle and up again (at 119.14).”

The first kiss, the osculum part of the gradus amoris convention is completely sabotaged by Van, when he fails to kiss the biblically honeyed lips (Cant. 4:9-12, “my sister, my spouse... .Thy lips.. .drop as the honeycomb...”) of the expectant Ada at her breakfast, causing her “tower” to crumble. And (save for that strange accidental (parodic?) “osculum” of 94:18, of course) real, intentional kissing is deferred to page 100:2-101:6 with Van’s erotically described “butterfly kisses” on Ada’s hair, while she paints, and then on her neck. These superficial and unsatisfactory near kisses result in Van’s need thereafter to seek solitary sexual relief, at his own hand, as it were. But it is Ada herself who, again inverting custom and taking the initiative, “shut her eyes and pressed her lips to his” (p. 101, lines 9-10), just as it had been she who spoke first, and who took Van by the hand. And the kissing begins in earnest, with vivid descriptive narrative in Chapter 17, starting with nicely ambiguous “dictionary” definitions of “lip” - a word repeated on these two pages (102 and 103) much like the recurrence of visual words cited above, including a startling use of the term “nether lip.”

Finally, to round out Nabokov’s parodic instantiation of the gradus amoris theme (discounting Van’s self induced climax as previously mentioned) the first “id” the first completed sexual act between our Edenic pair is in the library where Van had gone down the spiral (yes) stair, where Ada brings him to climax manually: with a hand job (115:20). After these two

[35]

parodic masturbatory undercuttings of the “fait," the first actual coupling of our lovers finds Van approaching Ada from the rear (his typical procedure as described by Brian Boyd in Nabokov's Garden |Ann Arbor: Ardis 1985, especially p 114]). But again it is Ada who takes the initiative, and she turns over onto her back (as Nabokov reminds us Juliet had been told she would do, with Shakespeare thus neatly joining Nabokov in “justifying” these amorous acts at such a tender age). This final flip leads the pair into their first many “faits.” It is also both clever and artistic of our author to recapitulate rapidly here the steps of the gradus with Van, “delighted” (116:27-8) to see Ada holding a long candle, in conversation with her touching and fondling her (117:9 ff) and kissing her, just before the first time they do the “deed'' After this first coupling they descend, still barefoot, the iron steps (122:8).

Every step of the traditional gradus amoris has thus been presented, every base touched, and in the prescribed order: but there has been much, much more. For Nabokov undercuts and trivializes each step of this set form: the first sight was not Ada; the first alloquia were not to each other; the first touch merely that of Ada’s hair on Van’s neck; the first kiss missed entirely at the honey breakfast, and the following merely butterfly kisses; and the first of Van’s “having sex with that woman,” pair of hand jobs. And Nabokov then embellishes them by orchestrating exuberant and repeated variations on them, as only the consummate master could.

— John A. Rea, Emeritus, University of Kentucky

NABOKOV’S PENCIL (an exchange)

Testing an idea, I turned to the authority on pencil length in Invitation to a Beheading, with the following results:

[36]

PM: In Speak, Memory, Nabokov invites “[t]he future specialist in such dull literary lore as autoplagiarism” to collate Fyodor Godunov-Cherdyntsev’s experience with “the original event” (37), his clairvoyant vision of his mother’s purchasing the window display pencil from Treumann’s store on Nevsky Prospect. The investigation (as he implies in the foreword by giving the publication history of his memoir) involves the Russian Dar (The Gift) (1937-8); Conclusive Evidence (1951), Drugie berega (Other Shores) (1954), the English translation of The Gift (1963), and Speak, Memory (1966).

The Treumann pencil is “v poltora arshina dliny” (one and a half arshins long) in 1937; “okolo dvukh arshin v dlinu” (about two arshins long) in 1954, “a yard long” in 1963, and “four feet long” in both English memoirs, in 1951 and 1966.

Unlike Cincinnatus’ pencil (“as long as the life of any man”), which

shrinks as the day of his execution approaches, Nabokov’s childhood

pencil apparently grows with his experience; as the mirror image of vita

brevis, Nabokov’s pencil lives in his fiction and his memoirs (like

Cincinnatus’ shrinking one, which nonetheless cancels death), showing

that “ars longa est.” What do you think?

GB: If one takes an arshin at twenty-eight inches, then two of those come to about 140 cm, or slightly over four feet. This seems to hamper the incremental argument: first 3 1/2 feet (1 1/2 arsh), then 4 1/2 ft. (2 arsh.), then back to 3 (a yard), then 4 again. Psychologically, transnational isometry is very hard to attain, and perhaps the imagined difference of afoot in English terms appears to be somewhat greater than the polarshina to a Russian mind, despite reasonable evidence to the contrary. An abrupt change in the way of measuring space is not unlike the change in the way of reckoning time, with the special pang of calendaric confusion suffered by Russian exiles.

[37]

If anything, I see that the sum of the Russian measurements (eight feet) exceeds that of VN’s later, Englished, memory (seven feet). Then where is the growth? It is perhaps not about ars getting longer as one’s tooth does, but about the the arshin stretching over two feet as the shadow of the past gets longer “at the sunset of our years.”

PM: Still, why is the numerical progression mostly (Conclusive Evidence makes a 4-foot bump) in one direction— is it really meaningless? Following your conversion to inches, a comparison of the Russian and the English versions of The Gift and the memoirs shows that the Russian pencil is consistently longer than the English, 42 vs. 36 inches, and 56 inches vs. 48. Nabokov appears to deliberately create a balanced ambiguity: in English, the wording suggests an increase in length overtime, while the arshin, once translated, shows the Russian pencil to be consistently longer in fact than the English one, a realization of Tiutchev’s often misused line,“Arshinom obshchimne izmerit’.”

GB: Quite. But the preceding verse states that in that particular case reasoning should also fail. Do you believe, then, that VN’s mental measuring tape got stretched with time, or that he had some plagal arrière pensée at work here? You point out “the numerical progression in one direction” and wonder whether it has a meaning. But if the aggregate length of the Russian pencil in the fiction and the memoir is greater than that of the later the English versions of The Gift-1963 + SM-1966 by a full foot, then the direction seems to be at any rate regressive. What then could be its meaning still? The evidence seems inconclusive. I do not know whether the pencil really “drags its slow length along”, but I doubt that the word “deliberately” is right here. The “highly satisfying” pencil sharpener in Pnin and the transparent pencil in a later novel may, if put to cooperative work, supply enough shavings for a dissertation.

[38]

PM: Indeed. The biography of a pencil in Transparent Things would support the possibility that the series of pencil sizes has significance. Your reasoning leads me to conclude that 1) Fyodor the fledgling writer of 1937 and 1963 has a shorter pencil than Nabokov the memoirist of either 1951 or 1954 and 1966 (42+36=78 inches vs. 48/ 56+48=96/104) and 2) the Russian writer casts the longer shadow.

— PM = Priscilla Meyer and GB = Gene Barabtarlo

We invite others to submit notes in this dialogic format.

[39]

RUSSIAN POETS AND POTENTATES AS SCOTS AND SCANDINAVIANS IN ADA:

THREE “TARTAR” POETS PART TWO

by Alexey Sklyarenko

According to Vladislav Khodasevich, a poet of genius and Nabokov’s friend:

The heavy gift of secret hearing

Is unbearable for a simple soul.

Psyche falls under its weight.

(the closing lines of Khodasevich’s 1921 poem “Psyche! Oh, my poor one!”)

That gift of secret hearing proved too much for poor Aqua, as it did to Maria Lebyadkin. They paid the price of their sanity for it. But, despite her madness, Aqua’s prophetic powers serve as an obvious parallel to the prophetic gift of Lermontov, Dostoevsky and Blok. Only, unlike the Russian writers, who foresaw the future of their native country, Russia, Aqua foresaw the future of America (note that, on Antiterra, Russia is part of America). That Aqua’s prophesies about America are directly connected to Lermontov’s and Blok’s prophesies about Russia is confirmed by Aqua’s “Blokian” pseudonym and by the names of two other lands mentioned along with Scoto-Scandinavia and Palermontovia: the Riviera and Altar.

Both these names refer to Lermontov and Blok, but also to Pushkin (whose disastrous marriage started with an ill omen before the altar and ended in a duel near St. Petersburg’s Black River). In his 1824 poem “Nedvizhnyi strazh dremal na tsarstvennom poroge... ” (“A motionless guard dozed on the

[40]

threshold of the tsar’s palace..in whichNapoleon’s shadow visits tsar Alexander I, Pushkin draws the following map of Europe:

From the billows of the Tiber to the Vistula and the Neva,

From the lindens of Tsarskoe Selo to the towers of

Gibraltar...

Besides Tsarskoe Selo, dear to Pushkin’s heart, three European rivers are mentioned in these lines, as well as Europe’s southwestern extremity, Gibraltar (according to B. Boyd’s “Annotations to Ada19.27-29, the Antiterran “Altar” corresponds to our world’s Gibraltar). Interestingly, “altars” occur in the poem that was written only a few days after the one just quoted and is very close to it in subject: “Zachem typoslan byl i kto tebia postal?”(“What were you sent here for and who was he that sent you?”). The poet ponders in it on the role Napoleon played in history. The line, in which this word occurs, runs as follows:

The disrobed altars stayed empty.

The word “altar” that rhymes in Russian with “tsar” was favored by Pushkin (who often used it in the sense “sacrificial altar”). It occurs both in the drafts of his first “Reminiscences in Tsarskoe Selo” (1814) and in his last Lyceum anniversary poem (1836), “Bylа рога: nash prazdnik molodoi...” (“There was a time: our young feast...”), in which Pushkin surveys the historical events that he and his classmates have witnessed in the last quarter of a century:

The playthings in a mysterious game,

The embarrassed peoples rushed about;

And the tsars rose and fell;

And human blood crimsoned the altars

Now of Glory, now of Freedom, now of Pride.

[41]

It seems to me that Van’s description of the events that are believed to have happened on Terra in the first half of the twentieth century: “kingdoms fell and dictatordoms rose, and republics, half-sat, half-lay in various attitudes of discomfort” (5.5) is a parody of these lines by Pushkin. If this is true, we can suppose that there is a connection between “altars” mentioned in them and “Altar” as the name of a land on Antiterra.

The altars in Pushkin’s poem are crimsoned, even if metaphorically, by human blood, and, as we know, human blood in the twentieth century “flowed like a river” (tekla rekoi). This is a stock hyperbole in Russian, which was realized in the heavy fighting of Russians with the Chechens on the Valerik River (by a coincidence, this name translates as “river of death”). Lermontov, who participated in this battle as a soldier, describes it in his poem “Valerik” (1840):

And the carnage in the torrent

Continued for two hours. People fought

Like wild beasts, in silence, chest to chest.

The brook was dammed with bodies.

I wanted to scoop water with my hands...

(Both heat and fighting have wearied me).

But the turbid water Was warm, was red.

Lermontov, the author of the famous poem “Borodino” (1837), was a master of the battle-piece genre. He also was a brave soldier who could look danger in the face. But even he would have been horrified if he had seen battles and massacres of the twentieth century, when greater rivers (particularly in Russia) were turned into “valeriks,” in which blood streamed instead of water. Thi s blood crimsoned the altars of Freedom, Equality and Brotherhood. “The Riviera” (from the French rivière, a river), as the name of an Antiterran land, refers to the three European

[42]

rivers mentioned by Pushkin in his 1824 poem, hinting at Lermontov’s Valerik, while “Altar” refers to various altars in Pushkin (including the one in “Gibraltar”), hinting at those that human blood crimsoned so generously in the past century.

“The Riviera” seems suggestive not only of the Valerik, but also of two other Caucasian rivers that occur in Lermontov. In Speak, Memory (Chapter Eight, 3) Nabokov paraphrases the beginning of Lermontov’s long poem “Mtsyri” (1839) as follows:

The time-not many years ago;

The place-a point where meet and flow

In sisterly embrace the fair

Aragva and Kurah; right there

A monastery stood.

A little further, speaking of Lermontov’s romantic mountains, Nabokov cites two more lines from “Mtsyri”:

Rose in the glory of the dawn

Like smoking altars...

While two rivers-the Aragva, famous thanks to Pushkin’s poem “On the Hills of Georgia,” and the Kurah, the Caucasus’ longest river-are compared by Lermontov to two sisters embracing each other, he likens the Caucasian mountains to altars. In Ada, Nabokov plays on Lermontov’s comparisons in an erotic key. Ada deceives her husband (and so breaks the promise she gave at the altar) making love to her sister Lucette (3.3). The names of the two lands, the Riviera (“the land of rivers”) and Altar, foreshadow Ada’s conjugal infidelity to Andrey many years after Aqua’s death. But they also hint at the cruel betrayal committed by Demon in regard to his wife.

Aqua went mad soon after she married Demon Veen. Demon married Aqua (“led her to the altar’’') after he had spent a fortnight or so on the Riviera with Aqua’s sister Marina-as a

[43]

result of which nine months later Marina gave birth to Van (who was then abandoned to Aqua and registered as her son). The names of both lands where Aqua sought sanity–Altar and the Riviera–hint thus at the main cause of her madness: Demon’s infidelity and her doubts that Van is her, Aqua’s, son. Soon after the wedding, Demon bundled his wife off to a sanatorium and resumed his affair with Marina. His betrayal was even more cynical and much crueler than his daughter’s. In fact, Ada’s “adultery” seems an innocent game when compared to Demon’s crime. Nevertheless, the two betrayals had equally sad consequences. While Demon’s conduct eventually led to poor Aqua’s suicide, Ada’s infidelity played its role in the fate of Lucette, with whom she was unfaithful to her husband.

The betrayals of Demon and his daughter can be compared to those that Russian decadent poets allowed themselves in their private lives. These betrayals caused several suicides. For instance, the poet Valeriy Briusov, whose demonism was noted by many contemporaries and whose portrait became the last completed painting of Vrubel (who was obsessed with the figure of the Demon), is responsible for the death of the young poetess Nadezhda L’vova, who killed herself because of her unhappy love for him (the details of her suicide are described in Khodasevich’s essay “Briusov” and in Boris Sadovskoy’s narrative poem “Naden’ka”). In his article “The Holy Sacrifice” (1904) Briusov wrote: “Let a poet create not his books, but his life... We throw on the altar of our deity our own selves. Only a priestly knife that cuts the breast entitles one to the name of a poet.” Nevertheless, in his private life, he preferred to throw on the altar of his deity, whatever its name, and to cut with a priestly knife not his own self, but the pretty bodies of young females. How symbolic that the first name of the symbolist Briusov practically coincides with the name of the bloody river in Lermontov’s poem!

Deceptions of wives and frequent changes of mistresses were customary among Russian decadent poets. But, even

[44]