Download PDF of Number 17 (Fall 1986) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 17 Fall 1986

_______________________________________

CONTENTS

News by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Michael Juliar's Vladimir Nabokov:

A Descriptive Bibliography

By Stephen Jan Parker 18

Emigré Responses to Nabokov (I): 1921-1930

By Brian Boyd 21

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: D. Barton Johnson, Pekka Tammi,

Gene Barabtarlo 42

Abstract: Dana Brand, "VN's Morality of Art:

Lolita as (God Forbid) Didactic Fiction" 52

Lost in the Lost and Found Columns

by Brian Boyd 56

Abstract: Marilyn Edelstein, "Nabokov's

Impersonations: The Dialogue between

Foreword and Afterword in Lolita" 59

1985 Nabokov Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker 62

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 17, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[3]

News

by Stephen Jan Parker

"Présence de Vladimir Nabokov" was the full-page banner headline of the 24 March 1986 issue of Le Figaro Littéraire. The sub-caption continued: "Son œuvre à la fois classique et d'avant-garde s'impose comme l'une des plus importantes." France has rediscovered Nabokov. During the past several years new French translations of VN1 s works, along with the Ageyev affair, have put and kept VN in the spotlight. Translations of the three volumes of lectures (1984-1986) introduced Nabokov the teacher, and the belated publication of the first French translation of Strong Opinions (1985) provided the French with new perspectives on the man and artist. The Ageyev - Novel with Cocaine - Nabokov confusion served to keep VN a current topic [for details see the Miscellaneous section of the 1985 Bibliography in this issue]. The result has been a proliferation of essays, articles, and reviews . The September 1986 edition of Magazine Littéraire, for example, features VN on the cover and devotes fifty pages to him in the interior, and the rare 1964 Nabokov edition of L1 Arc has now been reissued in photo-reproduction as issue No. 99.

Most importantly, it is in France that Nabokov's 1939 Russian novella, Volshebnik, was published for the first time. Because The Enchanter is kin to Lolita, it was decided that it, too, should appear first in France. Gilles Barbedette rendered an excellent French translation from Dmitri Nabokov's impeccable

[4]

English translation of the Russian original. Released in September, L'Enchanteur quickly found its place on French best-seller lists. The US edition, with author's notes, translator' s note and an essay by Dmitri Nabokov, followed in October. Reviewing it in The New York Times Book Review (19 October) Edmund White termed the story "a heady combination of passion, humor and beauty," and closed by remarking that "almost ten years after his death, Vladimir Nabokov has provided us with the literary event of the season." It is expected that The Enchanter will be published in all major languages throughout the world during 1986/87 publishing seasons.

*

International wire services perked up at the discovery of one sentence on page 15 of the 23 July 1986 issue of Literaturnaia Gazeta, in the middle of an article by Mikhail Alekseev, Chief Editor of the Soviet literary journal Moskva. Gene Barabtarlo explains that this sentence, "said literally the following:

Dumayu, prispela рога vernut' nashemu chitatelyu V. Nabokova, ego roman "Zash-chita Luzhina" postaraemysa obnarodovat'.

Now, this particular (but very typical of the Soviet hieroglyphic style) farrago of abused colloquialisms ("prispela рога") and bombastic party cliches ("obnarodovat'") always defies attempts at a reasonably serious translation. If Joe Gargery, the blacksmith from Dickens's penultimate masterpiece, had been editor-in-chief of a Moscow literary magazine, he might have put it thusly: "I meantersay, the time

[5]

is a-ripen we give V. Nabokov back to our reader ["our reader" in the current Soviet patois means "the Soviet reader," not the magazine's]; as per his novel "Luzhin's Defense," why, we'll be а-trying to per-mule-gait it."

An even greater stir was caused by the publication of an excerpt from Drugie berega, the Russian version of VN's memoirs, in the August issue of the Soviet chess magazine 64. The published excerpt (Chapter 13, Part 4) is complete except for the deletion of one passage . Accompanying the excerpt is a brief piece under the title "Concerning Vladimir Nabokov" by Fazil Iskander, a well-regarded Soviet writer. Iskander remarks that "the time has come to publish [Nabokov] in his homeland." As noted in the international press, the memoir excerpt was the first official publication of Nabokov in the USSR.

When this writer was asked by an interviewer for National Public Radio's "All Things Considered" what these events might portend for further Nabokov publication in the USSR, the cautious reply was that the roundabout method of quietly publishing a writer in a relatively obscure journal rather than a major literary organ, without fanfare, was a not unprecedented way for the Soviets to reincarnate an undesirable. It is more difficult, However, to guess at future developments. Gene Barabtarlo, for one, doubts that the Soviets will be able to publish The Defense. "I, for one, don't believe that they would dare publish The Defense unmaimed. What would they do, for instance, with Chapter 13 in which a grotesquely Philistine wife of a

[6]

Soviet official comes from brand new Leningrad to stay with the Luzhins and to use Mme. Luzhin (who handsomely assumes that the lady is "probably a very unhappy woman — she's broken out temporarily to freedom") as a shopping guide to Berlin?" Barabtarlo notes that Moskva is also the journal which twenty years ago published "a ruthlessly mutilitated version" of Bulgakov's Master and Margarita.

*

Thomas Urban (Homburger Str. 9, D-6000 Frankfurt 90, West Germany) provided the following citations of references to VN in past USSR publications. They supplement information given in Paperno and Hagopian, "Official and Unofficial Responses to Nabokov in the Soviet Union" [Gibian and Parker, The Achievements of Vladimir Nabokov 99-118]:

— Krasnaia nov' (Moscow) 3 (1924) p. 265. Nikolai Smirnov characterizes VN's verse as smooth and slick and cites four lines as indicative of his "bourgeois style."

— Novy mir (Moscow) 6 (1926) p. 141. In an article on emigre literature, Nikolai Smirnov writes, "As to other poets (G. Struve, VI. Sirin, N. Berberova) we should keep silent."

— Don (Rostov) 12 (1965) p. 171. Leonid Usenko refers to Alexander Kuprin's characterization of Nabokov as the talented author of The Defense.

— Mirazhi i deistvitelnost'. Zapiski emigranta Moscow: Novosti, 1966, pp. 217-218.

[7]

Dmitri Meisner notes VN's talent, deplores the lack of a basic idea in his oeuvre, and attacks Lolita.

— Zvezda (Leningrad) 5 (1969) pp. 122, 124. Vadim Andreyev affirms that literary quality in the emigration was very low and thus Sirin could become "the best poet." He also notes that Sirin invented the Russian crossword.

— Ilya Ehrenburg. Sobranie sochinenii (Moscow) Vol. 8, p. 496 (in Liudi, godi, zhizn’). To Isaac Babel's reported praise of Nabokov, Ehrenburg adds: "He is able to write, but he does not know what about."

— Novy mir (Moscow) 2 (1969) p. 93. Babel refers to VN by name by reporting the comments of his young friend Osip: "'Ecoutez la chanson grise! ' Osip in a sad and dreamy manner cited this verse by Verlaine. I remarked that [Verlaine] had long loved 'écoutez '. His 'écoutez' found many imitators, for example V. Nabokov."

— Literaturnaia gazeta (Moscow) 4 March 1970, p. 5. In a five-column article by A. Chernyshev and V. Pronin titled "Vladimir Nabokov, vo-vtorikh i vo-pervykh...,” VN is attacked for "enmity to socialism" and his imitation of the fashionable Western tendencies of "cosmopolitanism, pornography and the absurd." He is also characterized as "anti-Soviet" and "denationalized."

— Literaturnaia gazeta 3 November 1971, p. 5. V. Shcherbina, referring to The Gift and Ada, chastises VN for writing consciously in a

[8]

style adapted to the liking of the public, combining elements of elite fashionable literature .

— Oleg Mikhailov. Strogy talant. Moscow: Sovremennik, pp. 263-266. Mikhailov refers to Drugie berega, several novels, and VN's Eugene Onegin.

*

More news about VN in the USSR comes from Christopher Hüllen (Palanterstr. 3 G, D-5000 КоIn 41, West Germany). He writes:

The scarcity and scantiness of official responses to Nabokov in the Soviet Union stands in marked contrast to the popularity he enjoys with Soviet readers. Although samizdat editions of his books or copies smuggled from the West are expensive and hard to get, Nabokov is - according to a statement made by Evgenii Evtushenko in a private conversation in 1984 - one of the most widely-read writers in the country of his birth. Slava Paperno and John V. Hagopian have mentioned examples of biographical research on Nabokov by "private scholars and devoted readers" in the Soviet Union who scorn the fact that publication of their findings is not very likely during the next few years. Reading Nabokov, however, proves to be dangerous at times. In January 1984, a Moscow court sentenced a man named Aleksey Kuznetsov to two years in prison. His case was heard behind closed doors. Among other things he was found guilty of having distributed pornographic literature. The incriminating evidence was an unspecified number of copies of Lolita found in his apart-

[9]

[10]

ment (cf. Yu. Vishnevskaya "Ruskiy Nabokov (K 85 - letiyu so dnya rozhdeniya)." Tribuna no. 6, May 1984 (New York) 20.).

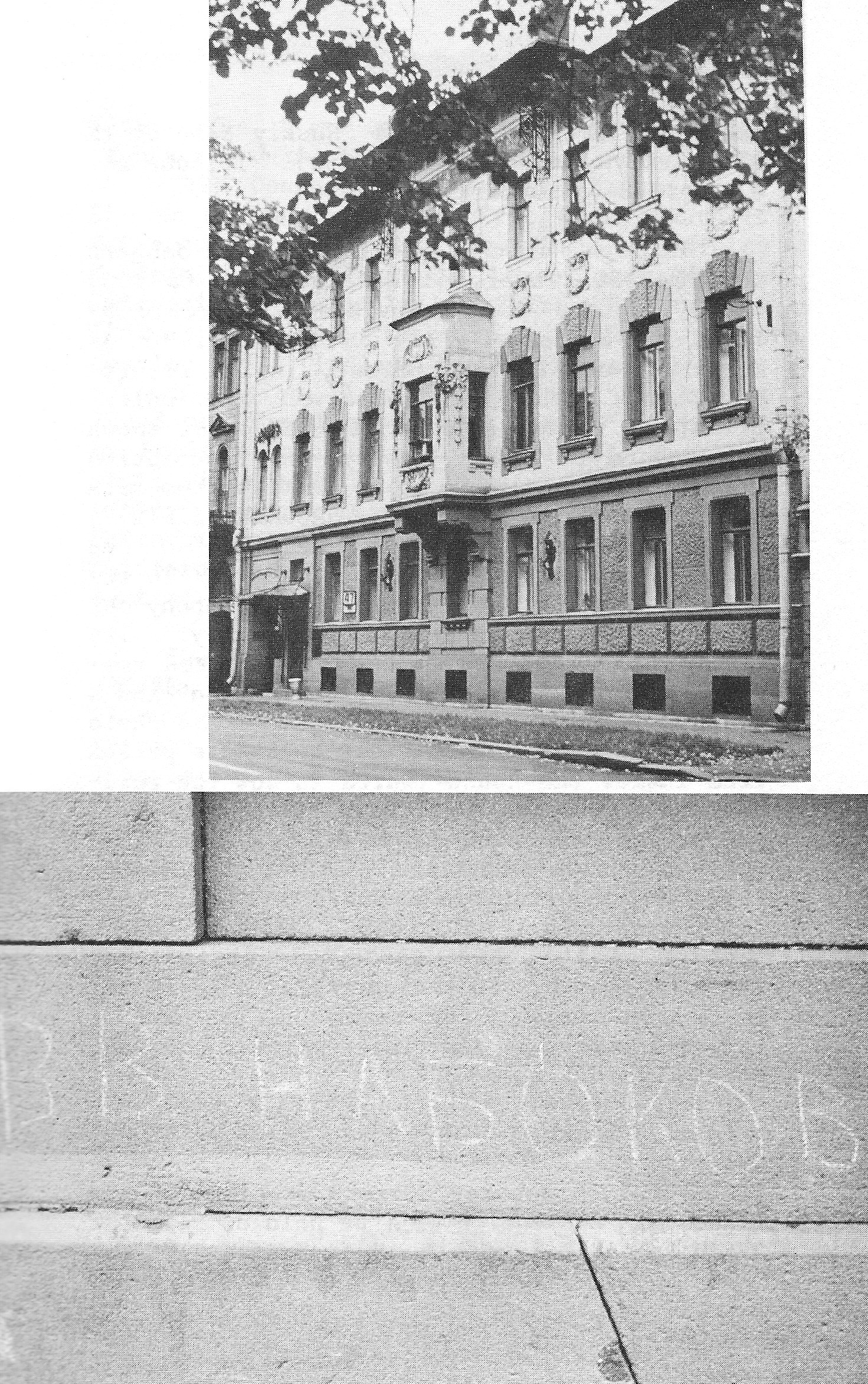

In light of the difficulties and dangers that Soviet readers of Nabokov have to cope with, a piece of Nabokoviana that could be found in September 1984 on the wall of 47 Morskaya, now Hertzen Street, in St. Petersburg, now Leningrad, deserves mentioning. Below the window shielded by the oriel known to readers of Speak, Memory, an inscription written with chalk in block letters commemorated Nabokov. It read "V V NABOKOV (SIRIN)", indicating the correct pronunciation of the name by a small stress on the first o. To the left of the initial V there was a sketchy but recognizable drawing of a butterfly. Its creator had signed the whole improvised commemorative plaque with the name "Semyon" and a long curved line ending in an X. The photo shows only a part of all this because a person from inside the house (which is now the residence of the "Management of publishing houses, polygraphy and book trade of the Leningrad City Executive Committee of Peoples' Deputies") became suspicious and closely watched the photographer. A second attempt to take a picture of the whole inscription failed for the same reason. In the spring of 1985 it was no longer there. (My thanks go to Barbara Fafinski who saw the inscription first and pointed it out to me.)

*

The 1986 Nabokov Society meetings at the Annual MLA Convention will be held on December 27 in Suite 3742, the Marriott Hotel, New York

[11]

City. The first session, 7:00 - 8:15 pm, "Nabokov and the Short Story," will be chaired by Julian Connolly (University of Virginia). The participants include Eric Hyman (Rutgers University), Stephen Matterson (Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland), Leona Toker (Hebrew University, Jerusalem), Zoran Kuzmanovich (University of Wisconsin, Madison), and Charles Nicol (Indiana State University) The second session, 9:00 - 10:15 pm, "Nabokov on Freud and Freud on Nabokov," will be chaired by Phyllis Roth (Skidmore College). Participants will be Susan E. Sweeney (Brown University), Geoffrey Green (San Francisco State University), and Alan Elms (University of California, Davis). The Society's business meeting will follow.

The Nabokov Society Meeting at the Annual AATSEEL Convention will be held on December 29 at the Roosevelt Hotel, New York City. The session, "Translated Things: Nabokov's Art as Translation and In Translation," 3:15 - 5:15 pm, will be chaired by Dale Peterson (Amherst College). Participants will be John Kopper (Dartmouth College), Gene Barabtarlo (University of Missouri), Spencer Golub (University of Virginia), Priscilla Meyer (Wesleyan University), and Beverly Lyon Clark (Wheaton College).

*

Mrs. Véra Nabokov has provided the following list of VN's works received April - August:

April — Sprich, Errinerung, Sprich [Speak, Memory], tr. Dieter Zimmer. Zurich: Swidd bookclub Ex Libris.

[12]

April — Var i Fialta og Andre Novellen [Nabokov’s Dozen]. Oslo: Glydendal Norsk Forlag.

May — Habla, Memoria [Speak, Memory], tr. Enrique Murillo. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.

May — Lolita, tr. Enrique Tejedor. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.

May — Palido Fuego [Pale Fire], tr. Aurora Bernadez. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama .

May — Durchsichtige Dinge [Transparent Things], tr. Dieter Zimmer. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Rororo.

May — En Glemt Digter [A Forgotten Poet: six stories]”! Copenhagen: Nansensgade Antikvariat.

May — Speak, Memory extract in Judith Summerfield and Geoffrey Summerfield, Frames of Mind. New York: Random House.

June —"A View from the Pram" in Sally Emerson, A Celebration of Babies. London: Blackie and Son Ltd.

June — Pnin, tr. Enrique Murillo. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.

June — A Defesa [The Defense], tr. Luiz Fernando Brandao. Sao Paolo: Bradilian, L & PM editores.

[13]

June — "A Russian Beauty," tr. Dieter Zimmer in Zimmer, Unterhaltung an Bord der Titanic. Hamburg: Hoffmann and Campe.

June — Invitation to a Beheading excerpts, tr. L. Engelking. Literatura na Swiecie (Warsaw) no. 3, and no. 14.

July — Bend Sinister. Harmondsworth: Penguin, third reprint.

July — El Ojo [The Eye], tr. Juan Antonio Masoliver Rodenas. Barcelona: Editorial Anagrama.

August — L’Enchanteur [The Enchanter], tr. Gilles Barbedette; postface by Dmitri Nabokov. Paris: Rivage.

August — La Méprise [Despair], tr. Marcel Stora. Paris: Gallimard, Folio paperback.

August — Lolita excerpt. Die klassische Sau. Zurich: Hoffmans Verlag.

August — The Defense. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Twentieth Century Classics paperback edition.

*

— Two other Nabokov papers will be read at the AATSEEL meetings in New York. On December 28 (8:30-10:30, Fifth Avenue Suite), in the session titled "Parody and Satire in the Slavic Literatures," Richard Borden will present his paper, "Nabokov's Parodies of Childhood Nostalgia." On December 30 (10:15-12:15, Sutton Suite), in the session titled

[14]

"Russian Modernism: Art and Literature," Margaret Gibson will deliver a paper, "Observations on the Language of Nabokov's Poetry."

— Ardis (2901 Heatherway, Ann Arbor, MI 48104) informs us that Christine Rydel's A Nabokov’s Who’s Who, announced for publication in 1984, is now scheduled to appear in 1987. Volume I of Nabokov's Sobranie Sochinenii [Collected Works], containing both Mashen'ka and Korol', dama, valet will also be published in 1987. VN's Russian works now available from Ardis are Ania v strane chudes, Blednyi ogon', Vesna v Fial'te, Vozvrashchenie Chorba, Dar, Zashchita Luzhina, Lolita, Perepiska s ses-troi, Pnin, Podvig, Priglashenie na kazn', and Sogliadatai. The volumes of Nabokov's Russian works that are temporarily out-of-print (e.g., Stikhi, Drugie berega) will eventually be reissued in the Collected Works format.

— Publication of VN's writings in the People's Republic of China (never previously noted) dates to as early as a 1981 edition of Pnin (Shanghai: Yiwen Publishing House), with a second printing of 53,000 copies in 1982. The translator, Mei Shaowu, is associated with The Institute of American Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

— Shoshana Knapp (English Dept, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, VA 24061) brings to our attention the July-August 1986 issue of Harvard Magazine which features Philippe Halsman's well-known butterfly's eye view of VN on its cover. Inside is Philip Zaleski's article, "Nabokov's Blue Period," discussing Nabokov's lepidopterological work at Harvard. Included are several new photographs of Nabokov's butterfly specimens.

[15]

— D. Barton Johnson (Dept of German and Russian, University of California, Santa Barbara 93106) has a recent publication, "The Labyrinth of Incest in Nabokov's Ada," Comparative Literature 38, no. 3, 1986: 234-255. The text differs from a similar section in his book, Worlds in Regression (1985). He also brings to our attention Michael Seidel's Exile and the Narrative Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press 1986). Chapter six deals with Pale Fire and Ada.

— A lengthy interview of Gene Barabtarlo (Dept of Germanic and Slavic Studies, University of Missouri, Columbia 65211) on current Soviet literature and on Nabokov appeared last spring in the Russian emigre almanac, Internal Contradictions ["Pervoe litso edinstvennogo chisla." SSR: Vnutrennie protivorechia (New York: Chalidze Publishers) no. 15: 227-245].

— A new paperback release from Cornell University Press is N. Katherine Hayles, The Cosmic Web: Scientific Field Models and Literary Strategies in the Twentieth Century, 1984. Chapter 4 is entitled, "Symmetry, Asymmetry, and the Physics of Time Reversal in Nabokov's Ada."

— Gregor von Rezzori's "In Pursuit of Lolita" — "an odyssey in search of Nabokov's libidinous nymphet," with photographs appears in the August 1986 issue of Vanity Fair.

The following item comes from Sam Schuman (Guilford College, Greensboro, N.C. 27410):

*

[16]

"The May 1986 number of Yankee magazine includes a piece entitled "The Berth of the Blues" (p. 20), concerning the efforts to protect the habitat of the Karner Blue, or Lycaeides melissa nabokova. The article notes that this 'rarest butterfly in New England', was 'named for novelist and lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov, who first determined that it was a separate species.' It reports that the Karner Blue now appears to live only in one location, a 100-acre patch of scrub growth in an industrial park owned by a beer distributor in New Hampshire. The Nature Conservancy is working to protect the area. The article has a nice color picture of the butterfly and states, 'We're lucky that the Karner Blue is pretty. It makes it easier to protect.'"

*

A Nabokov symposium will be held at Yale University, February 13-15, 1987. Contact Vladimir Alexandrov for further information (Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures , New Haven, CT 06520) .

*

There will be no increase in annual subscription rates for 1987. Increased costs of postage have obliged us to raise the postal rates for all issues mailed outside the USA. The new rates: For surface postage outside the USA add $2.00 to the subscription rate. For airmail postage to Europe, add $4.00; to Australia, India, Israel, New Zealand add $5.00. For airmail copies of back issues, add $2.00 per issue.

*

[17]

Though there is no totally satisfactory system of transliteration of the Cyrillic alphabet into English, our policy has been to follow the guidelines established in J. Thomas Shaw's standard work, The Transliteration of Modern Russian for English-language Publications. Since The Nabokovian is intended for non-specialists as well as specialists in Russian studies, The Nabokovian employs the modified Library of Congress system, as follows:

a b v g d e e zh z i i k l m n o p r s t u f kh ts ch sh shch " у ’ e iu ia

We ask contributors to please adhere to this system of transliteration.

*

Our thanks to Mrs. Paula Malone for her continuing, invaluable assistance in the publication of The Nabokovian. Thanks also to Kurt Shaw for his indispensable help with this issue.

*

[18]

Michael Juliar's Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography

by Stephen Jan Parker

"To identify clearly and completely all of Nabokov's works that have been published in any form or fashion through 1985" was Michael Juliar's stated goal, and Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography (New York Garland,

1986; henceforth DB) is the impressive result of more than six years of his labors. The DB, a stout and lavishly illustrated xiii + 780 pages, holds a wealth of useful and fascinating information which greatly expands our knowledge of the dimensions of Nabokov's publications.

The core of the volume (410 pages) presents 56 major Nabokov titles listed chronologically by the date of publication, enumerating and describing all separate editions of each title published through 1985. The sections which follow are: Nabokov's scientific publications; separate publications with contributions by Nabokov; periodical appearances ; translations; pre-publication editions; braille and recorded editions; adaptations; interviews and remarks; drawings and ephemera; piracies; appendices; index.

Periodical appearances are first presented chronologically (1916-1984) and are then separately listed by (1) publications in which they appeared (2) type of contribution, (3) language of contribution. The translations of major titles are given chronologi-

[19]

cally, and then are separately listed by language (29 in all), country (30 in all) and year (1928-1985). Interviews are presented chronologically (1932-1983) and are then arranged by media entity. The appendices include (1) a chronology of Nabokov's literary career; (2) a translations summary; (3) a Lolita chronology, 1939-1973; (4) a list of major public depositories of Nabokov materials; (5) works consulted and an explanation of terms and abbreviations employed.

The method of notation (А-items, AA-items, В-items, etc.) requires some familiarization, but proves to be both practical and efficient. The keys to the volume are found in the elaborate 72-page index, which is a perfect example of the benefits of computer applications in the preparation of bibliographies. The thorough cross-referencing, and the ability to present information in the variety of organizational schemes which one finds in the DB, would hardly have been possible without the aid of a computer and a versatile software program.

Field's Vladimir Nabokov: A Bibliography [henceforth VNAB] revealed the general scope and intricacies of Nabokov's publishing history. The DB extends the Nabokov bibliography from 1971 (Field's cut-off date) to 1985. It surpasses the VNAB in completeness and accuracy, the two essential aspects of any bibliography. It incorporates the many corrections to the VNAB which have been noted over the years, and it proves to be more thoroughly researched and more carefully prepared than the VNAB. Field felt that the most important lacunae in his work were the absence of cita-

[20]

tions to first publications of seven short stories. Juliar has completed the citations for four of them. Field enumerated at great length the many problems he encountered as a Nabokov bibliographer; Juliar acknowledges the aid of others and demonstrates the results which are possible after thorough and meticulous work.

Juliar is aware that Nabokov's bibliography will continue to grow, and that readers will likely discover errors and omissions in this edition of the DB. He has asked that corrections, additions and comments be sent to him c/o The Nabokovian, along with suggestions as to how the computer-generated material might be otherwise arranged, particularly in regard to cross-referencing. The Nabokovian will disseminate this information in subsequent issues, and some day there will be a second, up-dated and revised edition of the DB.

Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography is an enormous achievement by Michael Juliar and its publication is a major event in Nabokov studies. Scholars, collectors, dealers, librarians, and readers now have the reliable and comprehensive Nabokov source work which has been so sorely needed. The DB is the new standard Nabokov bibliography.

[21]

Emigré Responses to Nabokov (I): 1921-1930

by Brian Boyd

One of the most charming passages in King, Queen, Knave depicts a motley cluster of people, each one precisely delineated, gaping at the first swallows of the spring. The list below, in soberer fashion, catches the disparate reactions of the Russian diaspora to the first flights of Nabokov's Berlin spring. At this stage, and even in early summer (see next issue, 1931-40), no sign of the swelling season seems too small.

Of course what appears below will not be complete, but I have recorded everything I have found that would not be a sheer waste of time for another reader to consult, noting even some very brief glances cast at Sirin in articles on other subjects, especially by critics of distinction like Adamovich or Khodasevich, Weidle or Struve.

This list supersedes the section "Emigré Reviews of Nabokov" in Andrew Field's Nabokov: A Bibliography. Field's file begins unpropitiously with three wrong items. When he enters "P. Sh." as the author of the first item, a review of Nabokov's first two emigre books of verse, Field's eyes have skipped to the byline on the next review on the same page of Rul'. In fact Grozd' and Gorniy put' were reviewed on that page (see item 10 below) by "В. K." (B. Kamenetsky), the pseudonym of Yuliy Aykhenvald, at that time the most distinguished critic in the emigration. Expelled

[22]

ten weeks earlier from Soviet Russia and forced to leave his family behind, Aykhenvald tried to spare them repercussions for his frequently anti-Soviet judgements by adopting this nom de plume. If the first item in Field's list masks the fact that Aykhenvald encouraged Sirin's work almost as soon as he arrived in the emigration, rather than two years later as Field's bibliography would suggest, the next two items both record the same review (item 17 below) with details missing or garbled. Field pulls out a rabbit, fumbles, lets it slip back into the hat, pulls it out again, and counts it as two rabbits--a special trick he manages to perform several times in the course of his bibliography.

To save fruitless future ferreting in libraries, I will say a word on sources.

By far the best archive of the Russian periodical press of the "first emigration" (1917-1940) is inaccessible. The contents of the Russkiy Zagranichnyy Istoricheskiy Arkhiv (Russian Historical Archive Abroad) in Prague were shipped back to Moscow as soon as the Soviets occupied Czechoslovakia in 1945. Without an entry to that material, I have tried to scan systematically the best holdings in the West (in Helsinki, Paris, Stanford and Berlin) and in Europe's Near East (Prague and Berlin) of, among others, the following journals:

Chisla (Paris)

Dni (Berlin, then (Paris)

Illyustrirovannaya Rossiya (Paris)

23]

Novaya Russkaya Kniga (Berlin)

Poslednie Novosti (Paris)

Rossiya (Paris)

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo (Paris)

Rul’ (Berlin)

Russkaya Kniga (Berlin)

Russkaya Mysl (Sofia, then Paris)

Segodnya (Riga)

Sovremmenye Zapiski (Paris)

Volya Rossii (Prague)

Vozrozhdenie (Paris)

Zveno (Paris)

(For further information on these and over a thousand other periodicals of the first emigration, see Tatiana Ossorguine-Bakounine, L’Emigration russe en Europe: Catalogue collectif des periodiques en langue russe 1855-1940 [Paris: Institut d'Etudes slaves, 1976] .)

My other source has been scrapbooks of clippings in the Nabokov archives. Not always accurately labeled, the clippings nevertheless include some items that would otherwise have escaped notice, such as those in Za Svobodu (Warsaw), Novoe Russkoe Slovo (New York), Ost-Europa (Berlin). Items from these scrapbooks that have not been checked against the originals are marked with an asterisk at the end of the entry.

Most items listed below are reviews of particular issues of periodicals in which Nabokov's work appeared. Field misleadingly labels a review of, say, an issue of Sovremennye Zapiski as "Review of The Defense" or "Review of Pilgram." Instead I record the periodical and issue number reviewed and then simply note the Nabokov works contained in

[24]

that issue: space and time do not permit further annotation, except to note when Nabokov' s contribution receives only a bare mention. To mark on the other hand a review wholly of one or more Nabokov works, I print the title(s) of the work(s) in capitals.

The order is strictly chronological according to the date a periodical appeared, whether or not the precise date was marked on the issue. Sovremennye Zapiski volumes, for instance, were usually marked only with the year of publication, but their appearance can usually be timed, by eyeing other emigre material, to within a week.

University of Auckland

Mark Tsetlin. Review of journal Zhar-Ptitsa 1.

[VN: poem "Krym" ("Crimea").]

Poslednie Novosti, 1 Sept. 1921 (#422), p. 3.

V.N. [Vladimir D. Nabokov]. Review of Russkaya Mysl’ 1921: V-VII.

[VN: poems "Stranstviya" ("Wanderings"), "Rossiya (Ne vsyo li ravno mne—raboy-li, nayomnitsey)" ("Russia" ["What do I care if a slavegirl or hireling"]).]

Rul’, 9 Oct. 1921 (#273), p. 7.

[Unsigned.] Review-notice of journal Spolokhi 1.

[VN: poem "Tristan" ("Tristram").]

Poslednie Novosti, 8 Dec. 1921, (#505), p. 2.

[25]

P. Sh. Review of almanack Grani 1.

[VN: poem "Detstvo" ("Childhood"), article "Rupert Bruk" ("Rupert Brooke")

Rul’, 8 Jan. 1922 (#348), p. 6.

I. G. Notice of journal Zhar-Ptitsa 4-5.

[VN: poem "Pero" ("The Feather"). Mention only.]

Rul', 8 Jan. 1922 (#348), p. 6.

Nikolay Yakovlev. Review of almanack Grani 1.

[VN: poem "Detstvo," article "Rupert Bruk"]

Novaya Russkaya Kniga (1922:1(Jan.), pp. 21-22.

Yuriy Ofrosimov. Review of translation NIKOLKA PERSIK (Romain Rolland's Colas Breugnon).

Rul', 19 Nov. 1922 (#602), p. 9.

A. В.———kh [Alexander Bacherac]. Review of book of verse, GROZD' (THE CLUSTER).

Dni, 14 Jan. 1923 (#63), p. 17.

VI. Kad. [Vladimir Kadashev]. Review of GROZD'.

Segodnya, 25 Jan. 1923.

В. K. [Yuliy Aykhenvald]. Review of books of verse GROZD’ and GORNIY PUT' (THE EMPYREAN PATH).

Rul', 28 Jan. 1923, (#658), p. 13.

Vera Lur'e. Review of GORNIY PUT'.

Novaya Russkaya Kniga, 1923:1 (Jan.), p. 23.

[26]

Gleb Struve. "Pis'mа о russkoy poezii, II" ("Letters on Russian poetry, II").

[VN: Grozd']

Russkaya Mysi', 1923:1-2 (Jan.-Feb.), pp. 292-99.

———— . Review of almanack Vereteno.

[VN: poems "My vernyomsya, vesna obeshchala" ("We'll be back, it's been pledged by the spring"), "Usta zemli velikoy i prekrasnoy" ("The lips of Earth, the beautiful and every blade of "Noch' brodit po polyam i kazhduyu bylinku" ("Night ranges o’er the fields and every blade of grass"), "Shepchut mne stranniki vetry" ("The wandering winds whisper to me")]

Russkaya Mysl', 1923:1-2 (Jan.-Feb.), pp. 374-76.

Arseniy Merich [Avgusta Damanskaya]. Review of almanack Grani 2.

[VN: play Skital1tsy, supposedly translated from the English original of Vivian Calmbrood

Dni, 1 April 1923 (#128), p. 14.

K. V. Review of GROZD'.

Zveno, 23 April 1923 (#12), p. 3.

V. Review of translation ANYA V STRANE CHUDES (Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland).

Rul', 29 April 1923 (#734), p. 11.

G. [Roman Gul']. Review of GROZD'.

Novaya Russkaya Kniga, 1923:5-6 (May-June), p. 23.

[27]

В. A[ratov]. Review of almanack Grani 2.

[VN: play "Skital'tsy"]

Volya Rossii, 15 June 1923 (#11), p. 91.

G. S. [Gleb Struve]. Review of ANYA V STRANE CHUDES.

Russkaya Mysl', 1923:3-5 [July], p. 422. '

A.L. Drozdov. "Literaturnye itogi (Pisateli russkoy emigratsii) 4: VI. Sirin"

Nakanune, Dec 2, 1923 (# 495), p. 6. [Ad hominen attack on Sirin as versifier.]

L. S. Ya: "Agasfer" ("Ahasuerus").

[Report of VN-Ivan Lukash pantomime, with text of VN's verse prologue.]

Rul', 2 Dec. 1923 (#911), p. 6.

[Unsigned]. Review of journal Zhar-Ptitsa 11.

[VN: poem "I v Bozhiy ray prishedshie s zemli" ("And those who've come from Earth to Paradise"). Mention only.]

Rul', 23 Dec. 1923 (#929), p. 9.

L. L. [Lolliy L'vov], Review of Agasfer.

Rul', 8 Jan. 1924 (#939), p. 5.

E. K-n. Review of unpublished play TRAGEDIYA GOSPODINA MORNA (THE TRAGEDY OF MR. MORN).

Rul', 6 April 1924 (#1016), p. 8.

I. Trotskiy. Review of journal Zhar-Ptitsa 12.

[VN: poem "Shekspir" ("Shakespeare")]

Dni, 13 July 1924 (#510), p. 8.

[Unsigned]. Review of journal Zhar-Ptitsa 12.

[VN: poem "Shekspir." Mention only.]

Rul', 23 July 1924 (#1104), p. 5.

V. Tatarinov. Review of journal Vestnik Obshchestva Gallipoliytsev.

[28]

[VN: poem "Kostyor." Mention only.]

Rul', 11 Feb. 1925 (#1274), p. 5.

Anton Krayniy [Zinaida Gippius]. "Poeziya nashikh dney" ("Poetry of Our Day").

[VN: general remarks on poetry.]

Poslednie Novosti, 22 Feb. 1925 (#1482), pp. 2-3.

[Unsigned]. [In column "Teatr i muzyka" ("Theater and Music").]

[Report of ballet performed in Konigsberg to music of A. Elukhen and scenario by VN and Evan Lukash.]

Rul', 25 March 1925 (#1310), p. 4.

B. Kamenetsky [Yuliy Aykhenvald]. "Literaturnye Zametki" ("Literary Notes").

[VN: poem 'La Bonne Lorraine."]

Rul', 13 May 1925 (#1350), p. 2.

[Unsigned.] [Editorial note accompanying poem "Krushenie" ("The Accident").]

Slovo (Riga), Feb.?) 1926, (#27).*

Yuliy Aykhenvald. "Literaturnye Zametki." [Review of novel MASHEN'KA (MARY).]

Rul’, 31 March 1926 (#1620), pp. 2-3.

Reprinted Segodnya, 10 April 1926 (#78), p. 8. Reprinted Russkoe Slovo (Kharbin), 22 May 1926.*

Gleb Struve. Review of MASHEN'KA.

Vozrozhdenie, 1 April 1926 (#303), p. 3.

[29]

S. Korev. Review of MASHEN'KA.

Slovo (Riga), 9 or 10 April 1926, pt. 8 [— Anatoly Alekseev]

A.S. Izgoev. "Mechta i bessilie" ("Dream and Impotence"). [Review of MASHEN'KA.]

Rul' , 14 April 1926 (#1630), p. 5.

K. Mochulsky. "Roman V. Sirina" ("Novel by V. Sirin"). [Review of MASHEN’KA.]

Zveno, 18 April 1926 (#168), pp. 2-3.

A. S[avelev]. [Savely Sherman]. Review of MASHEN'KA.

Poslednie Novosti, 29 April 1926 (#1863), p. 3.

A. [Prince D.A. Shakhovskoy, later Archbishop Ioann]. Review of MASHEN'KA.

Blagonamerennyy, 2 (March-April 1926), pp. 173-74.

N.M. P——k. [Nadezhda Melnikova-Papushkova]. Review of MASHEN'KA.

Volya Rossii,1926:5 [May], pp. 196-97.

Mikhail Osorgin. Review of MASHEN'KA.

Sovremennye Zapiski, 28 ([early June] 1926), pp. 474-76.

[Unsigned.] "Den' russkoy kul'tury v Berline."

[Report of public reading.]

Rul', 11 June 1926 (#1677), p. 4.

R. T. [Raisa Tatarinova]. "Sud nad 'Kreytserovoy Sonaty1" ("Kreutzer Sonata Trial").

[VN: report of "trial" of Pozdnyshev, hero of Tolstoy's "Kreutzer Sonata played by VN.]

[30]

Rul', 18 July 1926 (#1709), p. 8.

Ars. M. [A. Damanskaya] Review of MASHEN'KA.

Dni, 14 Nov. 1926 (#1159), p. 4.

Mikhail Osorgin. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 30.

[VN: story "Uzhas."]

Poslednie Novosti, 27 Jan. 1927 (#2136), p. 2.

Yuliy Aykhenvald. "Literaturnye Zametki." [Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 30.]

[VN: story "Uzhas."]

Rul’, 2 Feb. 1927 (#1877), pp. 2-3.

Diks. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 30.

[VN: story "Uzhas."]

Zveno, 13 Feb. 1927 (#211), p. 8.

Boris Brodsky [and V. Iretsky]. Review of performance of play CHELOVEK IZ SSSR (THE MAN FROM THE USSR)

Rul', 5 April 1927 (#1930), p. 5.

S. Postnikov. "0 molodoy emigrantskoy literature" ("On Young Emigre Literature").

[VN: Mary]

Volya Rossii, 1927:5-6, pp. 215-225.

P[yotr] P[ilsky]. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 33.

[VN: poem "Universitetskaya poema" ("University poem").]

Segodnya, 9 Dec. 1927 (#278), p. 6.

Gleb Struve. Review of "UNIVERSITETSKAYA POEMA" ("A UNIVERSITY POEM").

[31]

Rossiya, 10 December 1927 (#16), p. 3.

Georgy Ivanov. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 33.

[VN: "Universitetskaya poema."]

Poslednie Novosti, 15 Dec. 1927 (#2458), p. 3.

Diks. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 33. [VN: "Universitetskaya poema."]

Zveno, 1928:1 (1 Jan. 1928), pp. 60-61.

Yuliy Aykhenvald. "Literaturnye Zametki." [Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 33.]

[VN: "Universitetskaya poema."]

Rul', 4 Jan. 1928 (#2159), p. 2.

———— "Literaturnye Zametki." [Review of novel KOROL’, DAMA, VALET (KING, QUEEN, KNAVE).]

Rul', 3 Oct. 1928 (#2388), pp. 2-3.

Mikhail Osorgin. Review of KOROL', DAMA, VALET.

Poslednie Novosti, 4 Oct. 1928 (#2752), p. 3.

[Unsigned]. Review-notice of KOROL', DAMA, VALET.

Segodnya, 13 Oct. 1928 (#278), p. 8.

G.S. [Gleb Struve]. Review of KOROL', DAMA, VALET.

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 1 Dec. 1928 (#1), p. 4.

[32]

Georges Chklaver. "L*Esprit universel dans les lettres russes."

[VN: Mashen'ka.]

Bulletin de la Société d'Ethnographic de Paris, 1928.*

Mikhail Tsetlin. Review of KOROL', DAMA, VALET.

Sovremennye Zapiski, 37 (late Dec. 1928), pp. 536-38.

Arthur Luther. Review of MASHEN'KA and KOROL', DAMA, VALET.

Ost-Europa (Berlin), 4 Jan. 1929.*

K. Zaitsev. Review of Elsa Triolet, Zaschitniy tsvet.

[VN: Korol, Dama, Valet.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 23 March 1929, (#17).*

Gleb Struve. Review of Nicholas Arseniew, Die Russische Literatur der Neuzeit und Gegenwart.

[Reproaches Arseniev for omitting Sirin.]

Rossiya i Slavyantsvo, 30 March 1929 (#18), p. 4.

————. Review of Vladimir Pozner, Panorama de la littérature russe contemporaine. Reproaches Pozner for omitting Sirin.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 6 April 1929 (#19), p. 4.

Aleksandr Amfiteatrov. "Literature v Izganii" ("Literature in Exile.")

[VN: survey, esp. Mashen'ka, Korol', Dama, Valet.]

[33]

Novoe Vremya (Belgrade), 22 May (#2416) and 23 May (#2417) 1929.*

[Unsigned]. Notice of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 40.

[VN: Comment on novel Zashchita Luzhina (The Defense), Chs. 1-4.]

Vozrozhdenie, 17 Oct. 1929 (#1598), p. 3.

Pyotr Pilsky. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 40.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 1-4.]

Segodnya, 22 Oct. 1929 (#293), p. 3.

Georgiy Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 40.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 1-4.]

Poslednie Novosti, 31 Oct. 1929 (#3144), p. 2.

K. Zaitsev. "Buninskiy Mir i Sirinskiy Mir" ("Bunin's World and Sirin's World").

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, chs. 1-4.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstva, 9 Nov. 1929 (#50), p. 3.

Mark Slonim. "Molоdye pisateli za rubezhom" ("Young Emigré Writers").

[VN: Mashen'ka, Korol', Dama, Valet.]

Volya Rossii,1929:10-11 (Oct.-Nov.), pp. 100-18.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 40.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 1-4.]

Rul', 20 Nov. 1929 (#2733), p. 5.

[34]

Georgiy Adamovich. Review of Sovremennye Zapiski 40.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 1-4.]

Illyustrirovannaya Rossiya, 7 Dec. 1929 (#56), p. 16.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of story collection VOZVRASCHENIE CHORBA (THE RETURN OF CHORB).

Rul', 31 Dec. 1929 (#2765), pp. 2-3.

Pyotr Pilsky. Review of VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.

Segodnya, 12 Jan. 1930 (#12), p. 5.

Eos. "Sovremennye russkie pisateli v izbran-nykh otryvkakh" ("Contemporary Russian Writers in Selected Excerpts").

[VN: parody of Zashchita Luzhina.]

Rul', 19 Jan. 1930 (#2781), p. 8.

Pyotr Pilsky. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 41.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 5-9.]

Segodnya, 29 Jan. 1930 (#29), p. 3.

V. Zlobin. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 41.

[VN: brief mention of Zashchita Luzhina.]

Vozrozhdenie, 5 Feb. 1930 (#1709), p. 5.

Georgiy Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 41.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 5-9.]

Poslednie Novosti, 13 Feb. 1930 (#3249), p. 3.

————. "Literaturnaya nedelya" ("The Literary Week"). [Includes review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 41.]

[35]

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 5-9.]

Illyustrirovannaya Rossiya, 15 Feb. 1930 (#8), p. 16.

André Levinson. "V. Sirine et son joueur d'échecs."

[VN: survey article with review of ZASHCHITA LUZHINA.]

Les Nouvelles littéraires (Paris), 15 Feb. 1930 (#383), p. 6.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 41.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Chs. 5-9.]

Rul', 19 Feb. 1930 (#2807), pp. 2-3.

G[erman] Kh[okhlov]. Review of VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.

Volya Rossii 2 (Feb. 1930), pp. 190-91.

[Yuriy Ofrosimov]. "Literaturnyy vecher" ("Literary Evening").

[VN: Soglyadatay.]

Rul', 4 March 1930 (#2818), p. 6.

Nikolay Otsup. Review of Gayto Gazdanov, Vecher u Klera.

[VN: alleged influence of Proust]

Chisla, 1 [March] 1930, pp. 232-33.

Georgiy Ivanov. Review of MASHEN'KA, KOROL', DAMA, VALET, ZASHCHITA LUZHINA, VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.

Chisla, 1 [March] 1930, pp. 233-36.

Gleb Struve. "Zametki о Stikhakh" ("Remarks about Poetry").

[36]

[VN: review of poetry section in VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 15 March 1930 (#68), p. 3.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of journal Chisla 1.

[Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Rul' , 26 March 1930 (#2837), pp. 2-3.

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of journal Chisla 1.

[Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Vozrozhdenie, 27 March 1930 (#1759), p. 3.

Andrey Luganov. Review of journal Chisla 1.

[Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Za Svobodu (Warsaw), March 1930.*

M[ark] S[lonim]. Review of journal Chisla 1.

[Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Volya Rossii, 3 (March 1930), pp. 298-302.

D. Filosofov. [Article on Gazdanov.]

[VN: on Proust questionnaire in Chisla 1.]

Za Svobodu (Warsaw), 2 April 1930 (#3070).*

Kirill Zaitsev. Review of journal Chisla 1.

[Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 5 April 1930 (#71), p. 4.

[Unsigned]. "Literaturnye Nravy" ("Literary Manners").

[37]

[Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Rul', 9 April, 1930 (#2849), p. 5.

Mikhail Tsetlin. Review of VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.

Sovremennye Zapiski, 42 ([April] 1930), pp. 530-31.

S. Nalyanch. "Poety 'Chisel'" ("Chisla1s Poets").

[VN: on Ivanov's attack and VN's poetry.]

Za Svobodu (Warsaw), (April-May?) 1930.*

Pyotr Pilsky. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 42.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Ch. 10-end.]

Segodnya, 10 May 1930 (#129), p. 3.

Vladimir Weidle. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 42.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Ch. 10-end.]

Vozrozhdenie, 12 May 1930 (#1805), p. 3.

Georgiy Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 42.

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Ch. 10-end.]

Poslednie Novosti, 15 May 1930 (#3340), p. 3.

Gleb Struve. "Tvorchestvo Sirina" ("The Art of Sirin").

[Survey article.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 17 May 1930 (#77), p. 3.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 42.

[38]

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina, Ch. 10-end.]

Rul', 21 May 1930 (#2882), p. 2.

Georgiy Adamovich. "Literaturnaya nedelya." [Includes review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 42.]

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina. ]

Illyustrirovannaya Rossiya, 14 June 1930 (#25), p. 18.

Arthur Luther. Review-notice of ZASHCHITA LUZIMA.

Ost-Europa, May 1930.*

Vladimir Weidle. "Russkaya Literafura v Emigratsii: Novaya Proza" ("Russian Literature in the Emigration: NewProse").

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina.]

Vozrozhdenie, 19 June 1930 (#1843), pp. 3-4.

————. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 43.

[VN: story "Pilgram" ("The Aurelian)."]

Vozrozhdenie, 24 July 1930 (#1878), p. 3.

Nikolaj Federof. "Majstori Nove i Najnovij e Ruske Knjivzevnosti, V.V. Sirin i A.N. Tolstoy."

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina.]

Novosti (Zagreb), 27 July 1930 (#205).*

Pyotr Pilsky. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 43.

[VN: "Pilgram."]

Segodnya, 31 July 1930 (#209), p. 3.

[39]

Georgiy Adamovich. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 43.

[VN: "Pilgram."]

Poslednie Novosti, 7 Aug. 1930 (#3424), p. 3.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 43.

[VN: "Pilgram."]

Rul', 15 Aug. 1930 (#2954), pp. 2-3.

S. Nalyanch. Review of VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.

Za Svobodu (Warsaw), ? Aug. 1930 (#209).*

Anton Krainy [Zinaida Gippius]. "Literaturnye Razmyshleniya" ("Literary Reflections").

[VN: on Ivanov’s attack and reactions.]

Chisla 2-3, Aug. 1930, pp. 148-49.

G. Fedotov. [Answers to questionnaire.] [VN's and Bunin's importance for emigration. ]

Chisla 2-3, Aug. 1930.*

Lolly Lvov. Review of "Pilgram."

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 6 Sept. 1930 (#93), pp. 3-4.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of ZASHCHITA LUZHINA (book).

Rul', 1 Oct. 1930 (#2994), p. 5.

Georgiy Adamovich. "Literaturnaya nedelya."

[VN: Zashchita Luzhina.]

Illyustrirovannaya Rossiya, 4 Oct. 1930 (#41), p. 15.

[40]

Vladislav Khodasevich. Review of ZASHCHITA LUZHINA.

Vozrozhdenie, 11 Oct. 1930 (#1957), P- 2.

M. V. Review of ZASHCHITA LUZHINA.

Novoe Russкоe Slovo (New York), ? Oct. 1930.*

Vladimir Weidle. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 44.

[VN: novella Soglyadatay (The Eye).]

Vozrozhdenie, 30 Oct. 1930 (#1976), p. 2.

Nikolay Andreev. "Sirin."

[Survey article.]

Nov’ (Tallin), Oct. 1930 (#3), p. 6. Translated by Andrew Field in his The Complection of Russian Literature

(London: Allen Lane, 1971), and in Phyllis Roth, ed. , Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1984), pp. 49-55.

A. Savelev [Savely Sherman]. Review of journal Chisla 2-3.

[On Gippius's defense of Ivanov's attack on VN.]

Ru'l, 5 Nov. 1930 (#3024), pp. 2-3.

Pyotr Pilskiy. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 44.

[VN: Soglyadatay.]

Segodnya, 8 Nov. 1930 (#309), p. 3.

Kirill Zaitsev. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 44.

[41]

[VN: Soglyadatay.]

Rossiya i Slavyanstvo, 15 Nov. 1930 (#103), p. 4.

Georgiy Adamovich. "Literaturnaya nedelya.” [Includes review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 44. ]

[VN: Soglyadatay.]

Illyustrirovannaya Rossiya, 22 Nov. 1930 (#48), p. 22.

————. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 44.

[VN: Soglyadatay.]

Poslednie Novosti, 27 Nov. 1930 (#3536), p. 2.

Sergey Yablonovsky. Review of SOGLYADATAY.

Rul' 1, 6 Dec. 1930 (#3050), p. 2.

A. Savelev [Saveley Sherman]. Review of journal Sovremennye Zapiski 44.

[VN: Soglyadatay.]

Rul’, 10 Dec. 1930 (#3053), p. 3.

Arthur Luther. "Geistiges Leben." [Review of ZASHCHITA LUZHINA.]

Ost-Europa (Berlin), 3 (Dec. 1930).*

N.R. (N. Rezuilov) Review of VOZVRASHCHENIE CHORBA.

Rubezh (Harbin). No. 33, 1930, p29.

[42]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.]

Two Notes on Literary Allusions in The Eye

1. Murochka,The Story of a Woman's life

In a recent essay ("The Books Reflected in Nabokov's The Eye," SEEJ 29, No. 4, 393-404), I surveyed the literary subtexts in Nabokov's least known longer work. Just as in Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, characters are typified by their reading habits. The centerpiece is the 1920 French novel Ariane, Jeune Fille Russe, written by Jean Schopfer under his nom-de-plume Claude Anet, a particular favorite of Matilda, who invites Smurov to her apartment to borrow the lurid tale and seduces him. Ariane is not the only subtext used by Nabokov in The Eye, nor is Matilda Smurov's first lover: "Before her, I was loved by a seamstress in St. Petersburg. She too was plump, and she too kept advising me to read a certain novelette (Murochka, the Story of a Woman's Life)" [Murochka, istoriia odnoi zhizni] (p.15/Russian p. 7). This parallel leads Smurov to reflect on the pointlessness of his

[43]

flight from one Philistine world into another, from seamstress to Matilda, from Murochka to Ariane. Each woman is defined by her reading taste.

At the time of writing the article, I was unable to identify Murochka, istorija odnoi zhizni. I now propose that Nabokov had in mind the often reprinted 1903 Istoriia odnoi zhizni, "The Story of a Woman's Life," by Anastasiia Alekseevna Verbitskaia (1861-1928). Verbitskaia, according to the Yale Handbook of Russian Literature, wrote chiefly about "questions of sex and the emancipation of women." Her involved plots, exalted style, and candid love scenes made her so popular in the early 1900s that "she was considered a rival of Tolstoy even though most critics did notice the vulgarity and pseudo-intellectualism of her works." Her books were precisely the kind of thing that Petersburg seamstresses would be likely to read and regard as profound: flaming manifestoes of the progressive, sexually emancipated, semi-literate working woman.

The Story of a Woman's Life tells of the tribulations of Olga Devig. Endowed with beauty and riches, she rejects her cold mother and her fortune to earn an impecunious living teaching music in her former school. She is encouraged in this by friends, a woman doctor and her brother, apparently a revolutionary. Living on the edge of starvation, she scrapes together her kopecks so that she may go to medical school. She vows never to marry. Her self-sacrifices and dreams come to naught, however, for she falls in love with a wastrel, a handsome officer. Her proud, independent nature collapses, and she becomes his spine-

[44]

less, jealousy-wracked plaything. The only one of her former ideals to which she remains true is not to marry, even though she bears her lover's child, which dies. Her lover eventually betrays her for an affluent provincial Miss. Olga throws in her lot with the radicals and years later her former lover reads of her sensational trial for some unspecified feat of daring. Obviously, the heroine has triumped over her emotions and performed the feat of social idealism dreamed of in her youth.

Verbitskaia's Story of a Woman's Life is the Russian equivalent of Schopfer/Anet's Ariane, Jeune Fille Russe, and it fulfills the same role in Nabokov's book. Like Ariane, Verbitskaia’s heroine is used as a role model by one of Nabokov’s women characters who wishes to see herself as a beautiful, strong-willed, passionate, emancipated creature and, perhaps even more, to convey that image to poor, passive Smurov. Both women try to force their favorite books (as well as their bodies) on the insubstantial Smurov who has acute identity problems of his own.

One problem with our suggested identification is that the "Murochka" of Nabokov's title does not appear in Verbitskaia's, nor is her heroine’s name Morochka. I do not pretend to know why Nabokov might have "disguised" Verbitskaia's book. Possibly the name was added to establish the parallel to Ariane, Jeune Fille Russe, and perhaps the resonance of murky "Murochka" with shadowy "Smurov" is relevant to the particular name chosen.

[45]

The paired hooks contribute a neat structural symmetry to The Eye: Smurov's two plump Philistine mistresses, the Petersburg seamstress and the Berlin bourgeoise, both define their images for themselves (positively) and for the knowing reader (negatively) by their similar reading habits. Nabokov's covert equation of Verbitskaya and Schopfeer/Anet has a further implication for his feud with the literary leaders of the emigration. Dmitri Merezhkovsky, Zinaida Gippius, Aleksei Tolstoy, and even Ivan Bunin had praised Ariane. Verbitskaia, whose inept writing and vulgarized Nietzschean view were generally mocked by the literary intelligentsia, would have been anathema to members of the Merezhkovsky-Gippius circle. By equating Schopfer/Anet with Verbitskaia, the young Nabokov was indirectly indicting the emigre literary establishment.

— D. Barton Johnson, University of California at Santa Barbara

2. A Nosological Note on The Eye

In addition to the other "books reflected in Nabokov's Eye" well discussed by D. Barton Johnson [see above], the following occurrences might be noted. At the close of Smurov's dream about the stolen snuffbox, a character named Krushchov addresses the dreamer:

"Yes, yes," said Krushchov in a hard menacing voice. "There was something inside that box, therefore it is irreplaceable. Inside it was Vanya — yes, yes, this happens sometimes to girls ... A very rare phenomenon, but it happens, it happens." (The Eye, p. 98)

[46]

The final clauses of this excerpt read in the Russian original "v tabakerke koe-chto bylo ... da, da, eto inogda byvaet s devushkami, — ochen' redkoe iavlenie, —no eto byvaet, eto byvaet ..." (Sogljadataj, Paris: Russkie zapiski, 1938, p. 74). And, as it turns out, this all but duplicates the conclusion to Gogol's Nos (The Nose), where the narrator urges us to take his tale in earnest: "... vo vsem etom, pravo, est' chto-to. Kto chto ni govori, a podobnye proisshestviia byvaiut na svete, — redko, no byvaiut" (Sochinenija v dvukh tomakh, Vol. I, Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1973, 483). I.e., " ... there really is something in this all. Say what you will, but such things happen in this world, —rarely, but they happen."

As is often the case with Nabokov's allusive games, since the subtext has been located, its complements start cropping up at every cranny of the main text. Earlier in The Eye Khrushchov has been observed manipulating his nose, "tugging at it, or getting hold of a nostril and trying to twist it off" (p. 42; my emphasis). The two episodes where Smurov first rummages in Vanya's apartment (pp. 67-71) and then intercepts Roman Bogdanovich' s letter (pp. 89-96) in order to discover clues about his own identity point towards another story by Gogol: Diary of a Madman, where Poprishchin quite similarly finds an unflattering portrait of himself from a series of filched letters. Smurov's monologue at the end of The Eye may again hark back to Gogol' s Diary. And there are stylistic allusions to Gogol's output at large--e.g., the expanded "Gogolian" simile accompanying Smurov's meditations on suicide (" ... and like smoke,

[47]

vanishes the estate bequeathed to a nonexistent progeny," p. 28), which closely resembles the grand finale to Dead Souls celebrated by VN in Nikolai Gogol.

Even the consistent emphasis on dreams (versus "reality") which forms the thematic backbone of Nabokov's novel involves a nod towards Gogol. Smurov talks of "life's motley insomnia" (p. 29); he is haunted by a character named Kashmarin (pp. 46, 110 — from koshmar, "nightmare"); and he subsequently tries to pass off the whole of the phenomenal reality as a subjective illusion or a "dream" ("It is frightening when real life suddenly turns out to be a dream ... p. 108). But — as Nabokov keeps underlining through all these parodic tributes--it was of course Gogol who was the great originator of such a theme in Russian letters. It is fitting, then, that while Nabokov toys with Gogol’s devices in his novel, the latter's title for Nos is itself a small anagram in the Nabokovian manner. Reversed, the title reads Son ("dream" in Russian).

— Pekka Tami, University of Helsinki, Finland

A Note on Pale Fire

In his recent incisive Nabokov's Ada: The Place of Consciousness, Brian Boyd singles out several cases of curious transfigurations in Ada performed deliberately within a relatively compressed textual space (pp. 5-7); these cases had previously been cited by Charles Nicol as examples of Van's overlapping memories ("Ada or Disorder," Nabokov's Fifth Arc, p. 231). In the most interesting example. Van

[48]

starts out for a farewell tryst with Ada at the Forest Fork in the family limousine, then gallops off mounted on a steed (meanwhile, the waiting butler has turned into a groom). Even before proceeding to study the specific literary fission this stylistic knight’s move sets off (Boyd calls it "the illusion of continuous motion in a single direction," p. 6), the conditioned re-reader should be able to discern in it yet another countersign left in the book by the outer narrator.

Kinbote's note to 1. 408 of "Pale Fire” ("A male hand") lights upon Gradus's meanderings "in the vicinity of Lex" (near Montreaux) where, at Villa Libitina, he is escorted by Gordon Krummholz, "a musical prodigy and an amusing pet." The lad's loinguards undergo, in a quick matter of two pages, as many as five successive phases of metamorphosis, under the unflinching eye of the reminiscing annotates:

He had nothing on save a leopard-spotted loincloth. (p. 199)

... the graceful boy wreathed about the loins with ivy. (p. 200)

The boy ... wiped his hands on his black bathing trunks. (p. 200)

... the boy striking his flanks clothed in white tennis shorts. (p. 201)

... his Tarzan brief had been cast aside on the turf. (p. 201)

Of course, there is plenty to be noticed here

[49]

at the level of the narration: Gradus's characteristic unobservance and his specific inability to grasp classical allusions (registered by Kinbote one page earlier); the faunlet's "Alpine” surname (revealed in the Index); his "favorite flowers" (most likely orchids), and much more. Up a yard from the surface, however, it becomes clear that it is Kinbote who stages this parade of loinwear in his fondling memory, trying on his creature various more-or-less tight breechclouts: Gradus can see all this only "with some help from his betters" (p. 202). But from a still higher vantage point one can easily descry behind Kinbote's shoulder the shades of his betters. The last sentence of his note employs Nabokov's famous "and-and-and" syntax (discussed in the lecture on Bleak House) to let in the fatidic Vanessa Atalanta which appears at crucial junctures of the novel and an instant before Shade's poem comes to a close, and which is a fluttering emblem used by Aunt Maud and Hazel Shade to forewarn the poet (see my note in Nabokovian 13), and, on a different plane, used by the poet to alert the reader:

From far below mounted the clink and tinkle of distant masonry work, and a sudden train passed between gardens, and a heraldic butterfly volant en arrère, sable, a bend gules, traversed the stone parapet, and John Shade took a fresh card. (p. 202)

Before he takes the fresh card, let's review the one that Shade has just finished: the "Gradus near Montreux" episode was synchronized with Shade's work on ll. 406-16 (John and Sybil are watching the tube; their daugh-

[50]

ter is about to take her life). Lines 408-09,

A male hand traced from Florida to Maine

The curving arrows of Aeolian wars,

forecast not only the disaster at hand but also Shade's own dress rehearsal of death:

It was a year of Tempests: Hurricane

Lolita swept from Florida to Maine.

... And one night I died.(ll. 679-80; 682)

Everyone knows that this arrow, launched crosswise, leaves the limits of Shade's world and lands in the empyrean abode of his maker and the reader. Thus, depending on the elevation of the reader's mobile observatory, he is afforded a view of Gradus as Kinbote' s creation, or of Kinbote as Shade's creation (I think Kinbote's note to 1. 408 lends substantial support to Field's and Boyd's theory that it is Shade who wrote the poem and all — see Nabokov's Ada, p. 239, note 15), or of John Shade as the creation of the Creator of whom he knows nothing until all the nines of his poem have turned into zeroes.

— Gene Barabtarlo, University of Missouri (Columbia)

Query

Transparent Things hero, Hugh Person, suffocating in the final hotel fire, imagines that "Rings of blurred colors circled about him, reminding him briefly of a childhood picture in a frightening book about triumphant

[51]

vegetables whirling faster and faster about a nightshirted boy trying desperately to awake from the iridescent dizziness of dream life" (p. 104). This image echoes Mr. R's earlier direct pronouncement that "Human life can be compared to a person dancing in a variety of forms around his own self: thus the vegetables of our first picture book encircled a boy in his dream ... going faster and faster and gradually forming a transparent ring of banded colors around a dead person or planet" (pp. 92-93).

Mr. R. speaks of it as "our" (i.e., R.'s) book, so it presumably dates back at least to the early years of the century. Although Mr. R.'s first language is apparently German, it seems likely that the book was in French, for he refers to the "spinning ronde of "Potato père" and "Potato fils." There is another possible allusion to the volume in LATH. The aged writer Vadim recalls childhood nightmare dangers from which he could sometimes escape into "a region resembling ... those little landscapes engraved as suggestive vignettes — a brook, a bosquet — next to capital letters of weird, ferocious shape such as a Gothic В beginning a chapter in old books for easily frightened children" (p. 16).

The frightening children's book may, of course, not be real. But then, perhaps it is. I have exhausted the obvious sources and would be interested in hearing from Nabokovians who might have some ideas on the matter.

— D. Barton Johnson, Department of German and Russian, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106

[52]

ABSTRACT

"Vladimir Nabokov's Morality of Art: Lolita as (God Forbid) Didactic Fiction"

by Dana Brand

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual MLA Convention, Chicago, December 1985)

Although Vladimir Nabokov generally resisted efforts to find moral or satiric didacticism in his work, he is known to have had some very "strong opinions" about a wide range of moral and social issues. In several interviews, Nabokov asserted that the strongest of his social opinions is his advocacy of the right to unlimited freedom of thought and expression. Yet although Nabokov’s love of freedom was an important component of his affection for his adopted country, the author of Lolita appears to have had few illusions about the degree to which individual autonomy is actually respected in the United States. Like another European observer of America, Alexis de Tocqueville, Nabokov suggests in Lolita that the society which claims to have freed itself from traditional forms of coercive authority has evolved new and more covert forms to replace the old. All of the Americans Humbert encounters construct their identity and view of the world according to the images of normalcy provided by advertising, mass culture, and applied social science. Only Humbert the foreigner is able to resist the influence of these new and powerful forms of coercion.

[53]

Humbert resists the manipulation of the American commercial and social environment by responding to its images as if they were art: fantastic deceptions interesting in themselves and not for what they refer to. By doing this, Humbert drains these signs systems of the immanence necessary for their functioning. Americans like Charlotte and Lolita believe, "with a kind of celestial trust," that the felicity represented in ads and popular culture can actually be enjoyed, if one behaves correctly and purchases the advertised commodities. Advertising is, in this way, a false double of art, promising gratification and not simply "aesthetic bliss." By reducing ads and popular culture to aesthetic images and imposing his own form upon them, as he does when he transforms the neon signs and illuminated shop windows of a small town into jewels spread on black velvet, Humbert neutralizes the coercive force of the images and asserts his control over them.

Throughout the first half of the book, Humbert uses metaphors of photography, murder, and collecting to represent his characteristic interaction with reality: the separation of surface from substance in order to impose a personal pattern and meaning. To do this, he suggests, is morally innocent. Defending his love for Lolita before he actually sleeps with her, he compares it to the love of a "humble hunchback" for the projected image of an actress. Yet in this defense, Nabokov provides the moral terms with which to condemn Humbert for his behavior in the second part of the book. Art, as Humbert recognizes in his apologise, suspends the possibility of gratification. Nabokov's critique of Humbert, I

[54]

suggest, focuses on his overstepping of the bounds of art in his appropriation of Lolita. His nympholeptic images degenerate from art into advertising as Humbert comes to believe that he can actually have Lolita in the physical world. Losing his "aesthetic" independence, Humbert begins to treat Lolita as a commodity promised by the "advertisement" of his imaginative image. Sacrificing his ability to gratify himself, Humbert can only have the illusion of possessing Lolita by spending a great deal of money to buy things for her. When Lolita becomes, in this process, a commodity, Humbert becomes a consumer. He has left "the patrimonies of poets" and entered the marketplace, enthralled by a little girl as vulgar, energetic, flirtatious, seemingly innocent and yet manipulative as the American commercial environment itself. When his commodity, as commodities will, takes on a life and independence of her own, he progressively loses the happiness he would theoretically not have lost if he had continued to approach her as if she were a piece of art. In Humbert’s descent, we can see that just as advertisement is a false double of art in that it deceives a viewer into thinking that an object can be possessed in actuality and not merely in the imagination, consumerism is a false double of aestheticism in that it involves a dependence upon the actual rather than the merely imaginative possession of objects. The mechanism of this false doubling is represented by the fact that Humbert loses Lolita to Quilty. Quilty is a pop-cult American version of Humbert. He shares his appreciation of little girls, literature, puns, and purple smoking jackets but he is also a creator of popular culture and he appears in a cigarette advertisement.

[55]

Quilty lures Lolita away from Humbert with false promises which are the equivalent of the false promises of referentiality made by advertising and popular culture. When he finally has her, Quilty does to Lolita essentially what Humbert ended by doing to her. Yet Quilty had never loved her. For him, she had never been connected with Nabokov's sacred realm of art, that Humbert, by actually possessing Lolita, has profaned. In sum, Quilty may represent Humbert's degeneration, and specifically, the degeneration of Humbert's love into possession and his aestheticism into consumerism.

At the end of the book, Humbert kills Quilty and tries to return Lolita to the realm of art. Included, however, in his aesthetic recreation of his lost love is his moral realization that he has ruined her childhood. By representing Humbert's fall and highly qualified redemption, Nabokov reaffirms his association of art with "curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy." Yet in the process he may also be warning of the consequences of living in a culture in which the sinister deceptions of advertising are so much more powerful than the harmless deceptions of art and in which a desperately selfish quest for gratification is so much more common that the gentle, disinterested gaze of the aesthete. Whether or not he had any explicitly didactic intention, I believe that Nabokov has offered, in Lolita, one of the most interesting moral and satiric perspectives we have had on American consumer culture in the middle of the twentieth century.

[56]

Lost in the Lost and Found Columns

by Brian Boyd

By mischance my "Lost and Found Columns" was printed last issue from an uncorrected text, not the corrected and expanded one already sent off. Here are the omitted additions and corrections.

Poem in Russian, "Tihaya osen'" ("Quiet Autumn"), 20 Feb. 1921: first line should read: "U samogo kryl'tsa obryzgala mne plechi," "Right by the porch bespattered my shoulders."

Poem in Russian, 18 June 1921: title should read: "Bezhentsy" ("The Refugees").

Add:

Poem in Russian. "I.A. Buninu" ("To I.A. Bunin") ("Kak vody gor, tvoy golos gord i chist," "Like mountain streams, your voice is proud and clear"). Rul'. Berlin. 1 October 1922 (#560), p. 2. (Field 0456A; delete 0411.)

Poem in Russian, 3 October 1922: title should read: "V zverintse" ("In the Menagerie").

Add:

Letter in Russian. "Boykot sotrudnikov 'Nakanune'" ("Boycott of Nakanune Associates"), Rul'. Berlin. 12 November 1922 (#596), p. 9. (Field: before 1304. A group letter signed by Amfiteatrov-Kadashev, Gorny, Lukash, Nabokov, G. Struve, Tatarinov and Chatsky.)

[57]

Poems in Russian, in Al'manah Mednyy Vsadnik (c. Jan. 1923): second title should read: "Cherez Veka" ("Across the Ages").

Add:

Poems in Russian. "Ya gde-to za gorodom, v pole" ("I'm somewhere in suburban fields"), "I utro budet: pesni, pesni" ("And the morn will come: songs, songs"). Rul'. Berlin. 27 February 1923 (#683). (Field 0466 omits second poem, written 30 January 1923.)

Add:

Chess problem. Rul'. Berlin. 20 April 1923 (#726), p. 4. (Field: before 1220. Correction and solution to problems, Rul', 5 May 1923, p. 5.)

Add:

Chess problem. Rul'. Berlin. 5 May 1923 (#738), p. 5. (Field 1220. Solution, Rul', 19 May 1923 (#749), p. 6.)

Add:

Poems in Russian. "Ob angelah" ("On angels"): "Nezemnoy rassvet bleskom oblil" ("An unearthly sunrise flooded with brilliance"), "Predstav': my ego vstrechaem" ("Imagine: we meet him"). Rul'. Berlin. 20 July 1924 (#1102), p. 2. (Field 0496 misrecords first lines.)

Poems in Russian, 24 September 1924: title/ first line should read: "Otdalas' neobychayno" ("She gave herself strangely").

Note should read:

(Field 0502A. Reprinted, with title "Royal"' ("The Grand Piano"), in Gazeta Bala Pressy, 14 February 1926, Field 0530.)

[58]

Poem in Russian. "Kostyor" ("The Bonfire"), in Vestnik glavnogo pravleniya obshchestva Gallipoliytsev, 1924 first line should read: "Na sumrachnom chuzhbine, v chashche" ("In a gloomy foreign land, in a thicket").

Add:

Crossword puzzle in Russian. "Zagadka Perek-restnyh Slov" ("Puzzle of Crossed Words"). Rul'. Berlin. 19 April 1925 (#1330), p. 8. (No Field category. Solution Rul', 26 April 1925 (#1336), p. 8. Note that Nabokov has not yet invented the Russian word for "crossword," "krestoslovitsa.")

Poem in Russian, "Razgovor" ("Conversation"), 14 April 1928: first line should read: "Legko mne na chuzhbine zhit'" ("I have an easy life abroad").

Translation "Ptichka" ("Little Bird") from The Freud/Jung Letters, 1974, is of course from Pushkin's "Tsygany."

Add:

Speech, untitled. In I.V. Gessen, Gody izgnaniya. Paris: YMCA-Press, 1979, pp. 94-96. (Field 1308A. Speech in honor of Gessen's 70th birthday, 14 April 1935.)

[59]

ABSTRACT

"Nabokov's Impersonations: The Dialogue between Foreword and Afterword in Lolita"

by Marilyn Edelstein

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual MLA Convention, Chicago, December 1985)

We have developed a critical vocabulary, including such terms as "implied author" or "authorial persona," for analyzing an author's apparent presence within a novel. Yet, our expectations of and receptivity to a novel are also shaped by our encounters with the author's statements or appearances outside that novel. However, we have not yet developed an adequate framework for analyzing such extra-novelistic authorial statements and for evaluating their relationship to intranovelistic appearances of the author. Twentieth-century writers like Vladimir Nabokov have, through such relatively recent forms of public discourse as the interview, unprecedented opportunities to create a public persona which can, in turn, profoundly influence critical understanding of their novels. Through his extra-novelistic appearances in not only interviews but published letters and lectures, an autobiography, a biography, criticism, Nabokov is able to construct a public persona as artfully as he constructs his novels. We must learn to "read" this persona as carefully and critically as we read other items in the Nabokov canon.

[60]

In addition to this vast body of extra-novelistic statements by Nabokov, we have a substantial collection of texts existing on the threshold between the extra- and intra-novelistic—Nabokov's (in)famous Forewords. Examining the history of the preface reveals its doubly rhetorical status: historically a part of classical rhetoric (and thus of oral discourse), and persuasive and manipulative of the audience.

The inherently dialogic nature of all prefaces is given a further twist in Lolita, in which we have the rare opportunity to read both a Foreword, written in the fictional "voice" of the inimitable John Ray, Jr., Ph.D., and an Afterword, written in what most readers assume to be Nabokov's own "voice." Not only do both Foreword and Afterword engage in the typical prefatory "dialogue" with the reader, but they are also in dialogue with each other. Analysis of the interplay between the Foreword and the Afterword, and their relation to both Lolita and Nabokov's extra-novelistic statements provides some insight into the complex relationships between authors, texts, and readers.

Both Ray's and Nabokov's texts undertake many of the same conventional prefatory tasks: commenting on the origin of the work, generically placing it, discussing its moral dimension, responding to criticism, presenting general aesthetic theory. I examine the similarities and differences in the ways Ray and Nabokov-as-prefator handle these tasks. I examine the formal and stylistic features of Ray's Foreword (e.g., its existence in italics, its manic changes of tone and diction,

[61]

its imitation and parody of many prefatory conventions, especially those of 18th-century novel prefaces—including the convention of the author-as-editor itself ), and look at the ways its style and propositional statements seem alternately "Nabokovian" and "anti-Nabokovian." I assert that, although some critics have done so, we cannot simply assume that all of Ray's claims are ironic, while all of Nabokov's, in the Afterword and elsewhere, are "sincere," especially since both Ray’s and Nabokov’s claims are often self-contradictory. These contradictions are especially apparent when Nabokov and Ray discuss the possibilities of moral or didactic elements in fiction.

Yet, the contradictions and inconsistencies in Nabokov's extranovelistic and prefatory texts are supplemented by the connections and continuities which one can find there. Unreliability, gaps, contradictions need not prove fatal to the search for an "author" outside the novel any more than they do in the search for an "author" inside the novel.