Download PDF of Number 16 (Spring 1986) The Nabokovian

THE NABOKOVIAN

Number 16 Spring 1986

________________________________________

CONTENTS

News

by Stephen Jan Parker 3

Photographs 16

Abstract: Dale E. Peterson, "Nabokov and the

Poe-etics of Composition"

(AATSEEL paper) 17

Abstract: Julian W. Connolly, "The Otherworldly

in Nabokov's Poetry"

(AATSEEL paper) 21

Abstract: Priscilla Meyer, "Nabokov's Non-Fiction

as Reference Library: Igor, Ossian and Kinbote"

(AATSEEL paper) 23

Annotations & Queries by Charles Nicol

Contributors: Robert Bowie, H. J. Larmour,

Gene Barabtarlo, Robert Grossmith 25

Lost and Found Columns: Some New Nabokov Works

by Brian Boyd 44

[3]

NEWS

by Stephen Jan Parker

A major event of 1986 will be the appearance of Vladimir Nabokov's never before published 1939 work, Volshebnik. Translated by Dmitri Nabokov into English as The Enchanter, it will be published in the USA by G. P. Putnam's Sons. Editions will also be published in France (Seuil-Rivages), England (Picador), and Germany (Rowohlt). A volume of Nabokov's correspondence is also in preparation and scheduled for publication in 1987 by Bruccoli Clark. A second volume will follow.

A film version of Mary is being produced in Munich, Germany and the filming of another novel, Laughter in the Dark, will begin early this summer at locations on the French Riviera.

*

The major event in Nabokov studies in 1986 will undoubtedly be the publication of Michael Juliar's voluminous Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography. Mr. Juliar writes:

After six years of work, I have completed Vladimir Nabokov: A Descriptive Bibliography. Garland Publishing of New York expects to issue it in July as ISBN 0-8240-8590-6 and Garland title number H656.

[4]

The work bulks out to 780 pages with 202 photographs of title-pages, copyright-pages, dust jackets, and covers of first and important editions of Nabokov's works. Variants, states, issues, and subsequent printings of all of Nabokov's Russian, French, and English works are described in detail. Russian text is transliterated into the Roman alphabet.

The bibliography describes 56 A items (separate publications entirely or principally by Nabokov), 18 AA items (separate publications of scientific works), 34 В items (separate publications with contributions by Nabokov), 702 C items (periodical appearances, 259 D items (translations) , as well as prepublication copies of A items, Braille and recorded editions of A items, adaptations of A items, interviews and remarks, miscellaneous items, and piracies of A items. Also included is a selective secondary bibliography of monographs and five appendices: A chronology of Nabokov's literary career; a summary of translations made by Nabokov; a chronology of the creation, publication, and reception of Lolita; a listing of depositories; a listing of references and works consulted; and, a glossary of terms and abbreviations used in the work. A 73-page index of titles, first lines of poems, translated titles, translators, and books and authors reviewed or lectured on by Nabokov, concludes the work.

[5]

A useful feature of the bibliography is the computer-generated cross-references. Periodical items are listed chronologically, by periodical, and by composition type (poem, essay, novel excerpt) and language. Translations are listed by the A items they are translations of, by language, by country of publication, and chronologically. Interviews and remarks are listed chronologically and by the media entity (Playboy, The New York Times, the BBC) in which they appeared.

I strongly encourage all users and perusers of the bibliography to send their comments, corrections, and additions to this base of Nabokov knowledge to me, care of The Nabokovian. I will winnow, sort, edit, and number the information I receive in accordance with the guidelines I set up to produce the bibliography. The Nabokovian will then publish the results as an on-going updating of the work. I am also open to suggestions for further features based on the bibliography, such as new computer-generated cross-references.

*

The MLA and AATSEEL Nabokov sessions, and the annual meeting of the Vladimir Nabokov Society, held in Chicago this past December were well attended. On the program of the MLA session, chaired by Charles Nicol under the title, "Lolita at Thirty," were: (l) Ruth Knafo-Setton, "Humbert's Dolorous Haze: From

[6]

Ape to Art in Lolita; (2) Dana Brand, "Vladimir Nabokov’s Morality of Art: Lolita as (God Forbid) Didactic Fiction"; (3) Marilyn Edelstein, "Nabokov’s Impersonations: The Dialogue between Foreword and Afterword in Lolita"; (4) Alina Clej, "The Problematic Truth of Certain Confessions: An Analysis of Lolita"; (5) respondent: Samuel Schuman.

The AATSEEL program, chaired by Duffield White under the heading, "Nabokov: Poet, Playwright, Critic, Translator," included: (1) Dale Peterson, "Nabokov and the Poe-etics of Composition"; (2) Martha Hickey, "Nabokov’s Narrator as Playwright"; (3) Julian Connolly, "The Otherworldly in Nabokov’s Poetry"; (4) Priscilla Meyer, "Nabokov's Non-fiction as Reference Library: Igor, Ossian and Kinbote"; (5) Robert Bowie, "Nabokov's Influence on Gogol."

At the business meeting Julian Connolly was elected Vice President of the Nabokov Society.

*

AATSEEL will meet in December 1986 in New York City. Dale E. Peterson (Department of English, Amherst College, Amherst, MA 01002) will chair the Nabokov panel and Susan Sweeney will serve as Secretary. The title for the panel is "Translated Things: Nabokov’s Art as Translation and in Translation — The Drama of Word Play."

[7]

There will be two Nabokov sections at the 1986 MLA meetings, also to be held in New York City. Julian Connolly (Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22903) will chair a section under the heading, "Nabokov and the Short Story." Phyllis Roth (Department of English, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, NY 12866) will chair a section entitled "Nabokov on Freud, and Freud on Nabokov."

The chairs of the three sections welcome inquiries from persons interested in presenting papers.

*

Mrs. Vera Nabokov has provided the following list of editions of her husband's writings received October 1985 - March 1986:

October — Ada. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag (Rororo), reprint.

November — Fogo Palido (Pale Fire), tr. Jorio Dauster & Sergio Duarte. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Guanabara, softcover edition.

November — The Man from the USSR, tr. Dmitro Nabokov. New York: Harvest paperback, revised edition.

November — "On Hodasevich" (essay). In Twentieth Century Literary Criticism, Number 15. Detroit: Gale Research Co.

[8]

November — "Provence" (poem). In Laura Raison, compiler, The South of France. New York: Beaufort Books.

December — Machenka (Mary), tr. Marcelle Sibon. Paris: Fayard, Folio edition reprint.

December — Cosas Transparentes (Transparent Things), tr. Jordi Fibla. Barcelona: Ediciones Versal.

December — Die Kunst des Lesens (Lectures) "Cervantes-Don Quijote" (Volume 3 of Lectures), tr. Friedrich Polakovics. Frankfurt: S. Fischer Verlag.

December — Lolita. Paris: Gallimard, Folio edition reprint.

January — Ultima Thule (collection of short stories), tr. Anneke Brassinga and Peter Verstegen. Amsterdam: De Bezige Bij.

January — Sprich, Errinerung, Sprich (Speak, Memory), tr. Dieter Zimmer. Heinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, club edition.

January — Intransigeances (Strong Opinions) , tr. Vladimir Sikorsky. Paris: Julliard.

January — Mademoiselle 0 (Nabokov's Dozen), tr, Maurice and Yvonne Couturier. Paris: Julliard, "Presses Pocket."

January — "Lance" (story). In Schone Zukunftswelt. Munich: Vilhelm Heyne Verlag.

[9]

March — "Poshlost"' (essay). la D. L. Emblen and Arnold Solkov. Before and After. New York: Random House.

March — Lolita, intro. Pietro Citati. Milano: Mondadori, "Oscar" series reprint.

March — Ada, tr. Gilles Chahine and J-B Blandenier. Paris: Fayard, reprint.

March — Lolita (in Russian). Ann Arbor: Ardis, paperback reprint.

March — "Le Rasoir" (The Razor, story), tr. Laurence Doll. In Ecriture No. 25. Lausanne, winter 85/86.

*

With sincere apologies we note the omission of J. E. Rivers’ , "Proust, Nabokov, and Ada," from the 1984 Nabokov Bibliography. Professor Rivers' excellent article appears in Phyllis Roth, ed., Critical Essays on Vladimir Nabokov (Boston: G. K. Hall) 134-156.

*

Pekka Tammi (Tehtaankatu 34 d D 11, 00150 Helsinki 15, Finland) announces the publication of his book, Problems of Nabokov’s Poetics . A Narratological Analysis (ASSF, Series B, No. 231, 1985). He writes: "The text is x + 390 pp, with two Appendices, Bibliography, and Index. It is published by the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, and it deals

[10]

with narrative problems in VN's entire Anglo-Russian tvorchestvo. The approach is eclectic, combining aspects of Soviet, Continental, and American Structuralism with a close reading of representative texts from the Nabokovian corpus. The text is distributed by the publisher (Academia Scientiarum Fennica, Snellmaninkatu 9-11, 00170 Helsinki 17) and by Akateeminen Kirjakauppa (The Academic Bookstore), Keskuskatu 1,00100 Helsinki 10)."

*

Peter Lang Publishers announces the publication of Beverly Lyon Clark's Reflections of Fantasy: The Mirror-Worlds of Carroll, Nabokov, and Pynchon. According to the publicity release, "Clark extends recent theoretical work on fantasy by exploring the technique of the mirror-world in works by Lewis Carroll, Vladimir Nabokov, and Thomas Pynchon."

*

Andrew Field (P.0. Box 139, Paddington, Qld., Australia 4064) has written to inform us that Crown Press will publish his book, V.N., in 1986, and that a revised edition of his Nabokov: A Bibliography is in progress.

*

Leona Toker (Faculty of Humanities, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Mount Scopus, 91905, Jerusalem, Israel) has two recent publications: "Between Allusion and Coinci-

[11]

dence: Nabokov, Dickens, and Others." HSLA (The Hebrew University Studies in Literature and the Arts), 12 (Autumn 1984) 175-98, and "A Nabokovian Character in Conrad's Nostromo," Revue de littérature compare (January-March 1985) 15-29. Her other articles in press are: "Self-Conscious Paralepsis in Vladimir Nabokov's 'Recruiting' and Pnin," in Poetics Today; "Ganin in Mary-land: A Retrospect on Nabokov's First Novel," in the Nabokov Issue of Canadian-American Slavic Studies; "Nabokov and the Hawthorne Tradition," in the Scripta of the American Studies Center of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

*

Peter Evans (Setagaya-ku, Higashi Tamagawa 1-3-4, Tokyo, Japan) notes the following publication: Graham Law, "The question is which is to be master: Notes on Nabokov and Freud," Studies in Humanities, No. 19. (Faculty of Arts, Shinshu University, Japan, March 1985).

*

Paul Bennett Morgan (Clettwr Cottage, Trerddol, Machynlleth, Powys SY20 8PN, Wales) has an article, "Nabokov and the Medieval Hunt Allegory" forthcoming in Revue de littérature comparée. He writes, "it describes VN's allusive use of 14th-century 'stag-of-love' allegorical tradition in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, based on the character Nina Lecerf and the narrator's relationship with her."

*

[12]

David Field (DePauw University, Greencastle, IN 46135) delivered a paper entitled "Fluid Worlds: Solaris and Ada" at the panel on "Stanislaw Lem: Metascience and Metafantasy" at this year's MLA meetings. A longer version of the paper will appear later this year in Science-Fiction Studies.

*

Additional information on Nabokov publications in Poland and the USSR comes from Leszek Engelking. Several Nabokov stories have been translated in Poland, as follows: "Sceny z zycia podwojnego monstrum" ("Scenes from the Life of a Double Monster"), tr. from English by Teresa Truszkowska, in Przekroj (Cracow, No. 2090, 30 June 1985) 15-17; "Powrot Czorba" ("The Return of Chorb"), tr. from Russian by Leszek Engelking, in Literatura na Swiecie (Vol. 15, Nos. 8-9, August-September 1985) 175-85; "Sygnaly i symbole" ("Signs and Symbols"), tr. from English by Leszek Engelking, in Literatura na Swiecie (Vol 15, Nos. 8-9, August-September 1985) 186-193.

A citation in the USSR is: V. V. Bibikhin, S. A. Gal'tseva, I. B. Rodnyanskaya. "Literatumaya mysl' Zapada pered ' zagadkoy Gogolya'" in Gogol': Istoriya I sovremennost1. К 175-letiyu so dnya rozhdeniya. Sost. V. V. Kozhinov, E. I. Osetrov and P. G. Palamarchuk (Moscow: Sovetskaya Rossiya, 1985) 390-433. Nabokov is mentioned on pp. 391, 405, and 422. The text, entitled "'Obeskura-zhivayushchaya figura.' N. V. Gogol' v zer-

[13]

kale zapadnoy slavistiki," was printed in Voprosy literatury (No. 3, March 1984).

Several misprints in Mr. Engelking's report in the last issue of The Nabokovian (No. 15) should be corrected as follows: page

25, line 14, "Adamcyzk" should read "Adamc-zyk"; line 15, "portrzeby" should read "potrzeby"; line 17, "Engleking" should read "Engelking"; line 20, "250-257" should read "252-253"; line 25, "male" should read "mala"; line 28, "February 5-18" should read "February 5-28"; page 16, line 15, "Kro" should read "Kto"; page 27, line 14, "dyna" should read "dnya"; line 28, "sienyushchaya" should read "sineyushchaya"; page 28, the Polish title of Brandys1 book should read Miesiace.

*

Maurice Couturier (Faculté des Lettres et Sciences Humaines, Université de Nice, 98 Bd Edouard-Herriot, Nice, France) notes that Le Magazine Littéraire is preparing a special issue on Nabokov for next fall.

*

Edith Mroz (RD 2, Box 66 B, Dover, Delaware 19901) is presently working on a Ph.D. dissertation entitled, "Vladimir Nabokov and Romantic Irony: The Contrapuntal Theme." She writes, "the dissertation will begin with a series of arguments that link the parodic and the romantic elements in Nabokov' s work with theories on Romantic Irony as developed by the

[14]

'German. Romantics. I plan to introduce Romantic Irony as an umbrella term for the ongoing dialectic between enchantment and deception which, according to Nabokov, constitutes art. With the use of this term I shall examine Nabokov's parodic-ironic narrative techniques to demonstrate how they function in the context of his romantic commitment. The critical tools provided by the study of Romantic Irony should help to integrate views on Nabokov as a parodist or self-conscious stylist on the one hand, and as a romantic on the other. It will be seen that the seemingly subversive techniques of romantic irony, as employed by Nabokov, actually serve to guard the romantic legacy as it survives in the modern novel."

*

Susan Sweeney (English Department, Brown University, Providence, RI 02912) writes: "In one of his letters to Edmund Wilson from Cambridge (Letter 198, February 21, 1952), Nabokov remarks that 'We have a very charming, ramshackle house, with lots of bibelots and a good bibliothèque, rented unto us by a charming lesbian lady. May Sarton.' Evidently one of the bibelots made a particular impression on Nabokov. In Sarton's recent preface to the reissued biography of her beloved cat Tom Jones, The Fur Person, she describes his special relationship with Nabokov (pp. 8-9)."

Sarton writes: "Before Judy and I moved to 14 Wright St. in Cambridge, we lived for a few years in the early 1950s in a rented house at 9 Maynard Place. When Judy had a sabbati-

[15]

cal leave, we sublet to Vladimir Nabokov and his beautiful wife, Vera, and they were delighted to accept Tom Jones as a cherished paying guest during their stay. What a bonanza for a gentleman cat to be taken into such a notable family with kind Vera and Felidae-lover Vladimir! And to hear cat language translated into Russian." Sarton then recounts Tom Jones’ happy stay with the Nabokovs and a subsequent disastrous reunion of cat and Nabokovs several years later at the Ambassador Hotel in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

*

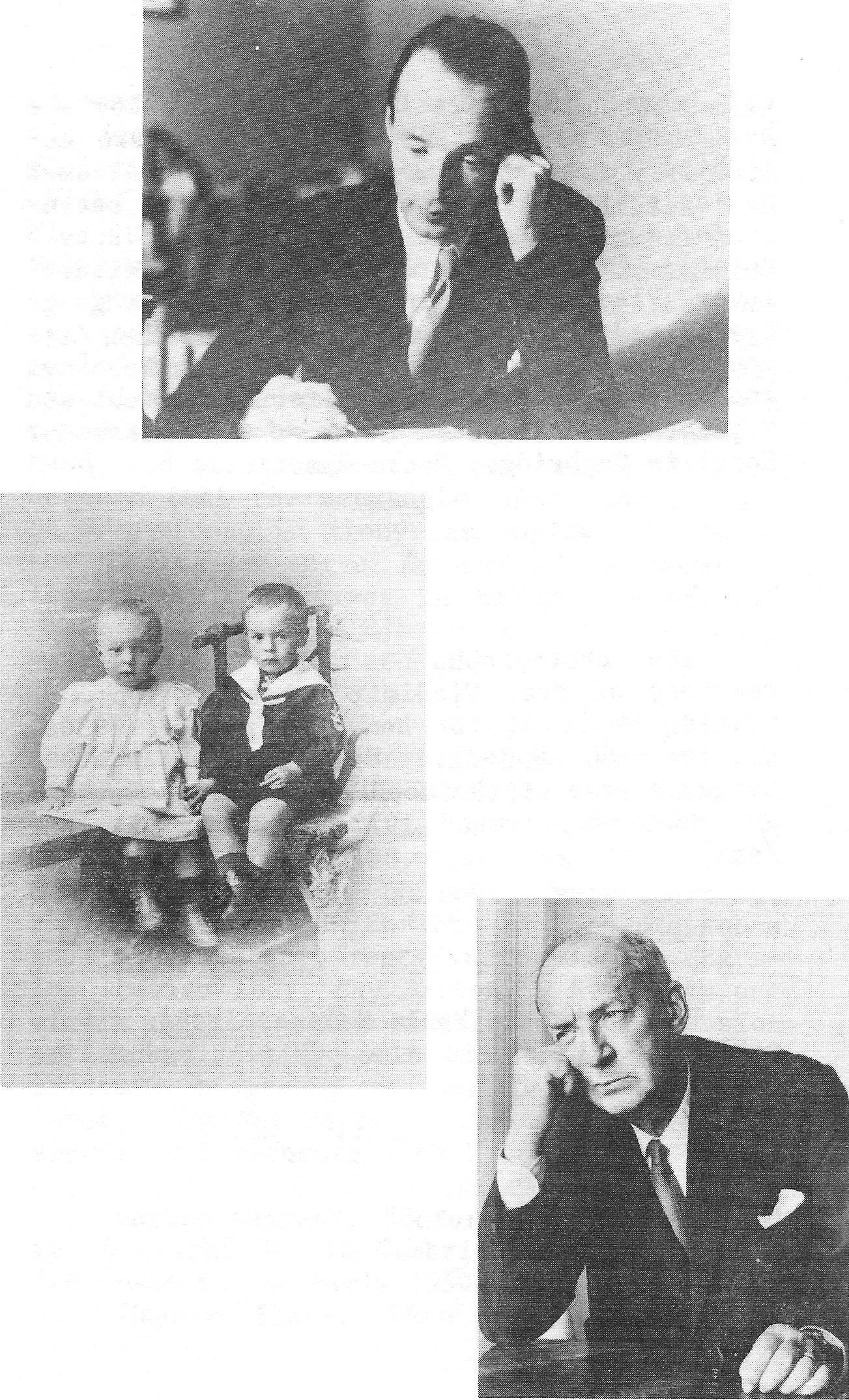

The photographs on page sixteen are courtesy of Mrs. Vladimir Nabokov. Top: VN writing while at the home of friends, 1930s. Middle: VN (in sailor suit) and his brother Sergey at one of the country estates. Bottom: VN, Montreux, around 1970 (photo by Gertrude Fehr).

*

Our thanks to Paula Malone for her invaluable assistance in the publication of The Nabokovian.

[16]

[17]

ABSTRACT

"Nabokov and the Poe-etics of Composition"

by Dale E. Peterson

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual Meeting of AATSEEL, Chicago, December, 1985)

The mark of Edgar Allen Poe left a ghostly trace in Nabokov's compositions both early and late. Most famously, Humbert's Lolita is transparently revealed as a warmed-over quotation from a haunting poem; as the recuperated image of an initial beauty bora in a Poe-etic atmosphere "in a princedom by the sea," Lolita herself is a visible mistranslation of "Annabel Lee." Yet when Nabokov selected Poe texts as pretexts for visible parody, he was also acknowledging a close affinity with the genuine spirit of Poe's poetry. Like Nabokovian parody, Poe-etry deliberately revealed itself to be a conscious, serious play with the transparent fraud of verbal substitutions for lost objects of desire.

Consider, for instance, one of Nabokov's favorite early lyrics, "V xrustal'nyj sar zakljuceny my byli," composed in the Crimea in 1918. What resonates in its sound and sense is a sympathetic chord for the music and standard libretto of Poe-etry. The lovelorn speaker of Nabokov's poem is a fallen angel permanently divorced from a barely recollected

[18[

communion with a spiritual twin. That speaker is committed, however, to the rebuilding of paradise through a euphonious speech and verbal tracery that imperfectly restore a perfect paradigm of bliss. Precisely like Poe's notorious "necrophiliac" lovers, Nabokov's singing angel devotes the power of an obsessed imagination to a spectral idol. What the author dramatizes is the willed substitution of a shadowy part for an irrecoverable whole.

In "The Return of Chorb" (1925) Nabokov was obviously and wittily retracing Poe's pathway in Gothic prose, relating the tragicomedy of a widower's project of repossessing, through reverse reconstructions of setting and scene, the virgin bride he had wed but not taken to bed. And much later, in his penultimate verbal performance, Transparent Things (1972), Nabokov was clearly restoring and elaborating upon a curious genre that Poe had pioneered: the posthumous dialogue among shades. In "The Conversation of Eiros and Charmion" (1839), as in Nabokov's work, a veteran of post-mortal life greets a newcomer just arrived on the verge of a "novel existence." Although a transfer into a new dimension has in fact occurred, earthly language is employed as a vehicle of illusory transport back into an obliterated existence. Whatever else it is, Transparent Things is a series of demonstrations illustrating how human perception "sees through" the physical and verbal signs given in any present moment. Both Poe and Nabokov invented prose fables that stage an exemplary intellectual comedy about the mind's unstoppable will to eliminate the

[19]

presented world in its consuming passion to retrieve a prior significance.

In Nabokov's writings, as in Poe's poems and apocalyptic prose, lyrical commemoration for what has been lost cannot be far removed from the spirit of parody. Since parody makes evident the mistranslation of an original text that is distorted but not beyond recognition, it is a form of utterance that is akin to poetry as understood by Poe. A Poe poem deliberately draws attention to its own substitutionary inadequacy, being in its obvious artificing of sound and image a pale reflection of the absent ideal it cannot replace. In theory and in practice, the Poe-etics of composition is radically Platonic. Poe's melancholy singers understand, like Socrates in the Cratylus, that mimesis always marks a loss since "names rightly given are the likenesses and images of the things which they name." Words knowingly employed at their beautiful best are but replicas and foreshadowings of an intuited wisdom that is eroded in the stream of mortal time.

Nabokovian parody was schooled in Poe's "Philosophy of Composition." Art is understood to be the diversionary play of creative memory, and the self-knowing poet may achieve some consolation and continued bliss through conscious parodies and admitted simulations of vanished moments of significance. It was no random coincidence that John Shade, Nabokov's representative artist, was both a master parodist and a close reader of Edgar Allen Poe. It is possible to lead a charmed double life so long as the intellect is aware of how

[20]

texts translate the irreversible actuality of the world into a new dimension of reflected reality. Aesthetic utterance is, after all, a pale fire, an arranged afterglow in the wake of a splendid intuition. For, in the words of The Gift, "the spirit of parody always goes along with genuine poetry."

English and Russian Depts.

Amherst College

Amherst, MA 01002

[21]

ABSTRACT

"The Otherworldly in Nabokov's Poetry"

by Julian W. Connolly

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual National Meeting of AATSEEL, Chicago, December 1985)

Recent Nabokov criticism has devoted considerable attention to investigating what might be called the metaphysical dimension of the writer's work. Refuting the concept that Nabokov was merely a literary trickster whose works are devoid of philosophical content, scholars have been studying the proposition that Nabokov's work posits the existence of two worlds: an immediate, visible world and a more comprehensive yet mysterious realm lying beyond this visible world. My paper examines the ways in which the notion of two realms is manifest in Nabokov's poetry, which often seems more open and frank than his later prose.

When viewed in a broad sense, the concept of two realms can be found in many of Nabokov's early poems, and one can divide such poems into four general categories: poems involving the poet’s thoughts about his distant homeland, poems about the poet and a loved one, poems about art and the nature of inspiration, and poems about a supernatural

[22]

"other" world itself — a world that exists beyond our physical dimensions and that can perhaps be comprehended completely only after death. There is a significant amount of overlap between these categories, and in describing the other world — the realm that is the object of the poet's thoughts — Nabokov often utilizes similar images and structures to evoke the special character of that world.

Focusing on poems in the last category in particular, my paper delineates Nabokov's treatment of several key themes: paradise,

the concept of life after death, and the relationship between earthly mortals and the denizens of the other world, especially angels . Nabokov1s vision of the afterworld is not entirely conventional, and his poems suggest that to leave life and to enter heaven entails a palpable loss. Ideally, it would seem, the realm of heaven is not a world to which one escapes from earthly life, but rather is a world of re-union with that which was once cherished on earth but which has since been lost through the ravages of time, exile, and death. The concept of two realms remains an important element in Nabokov's work over the course of his career, but he became more cryptic and guarded in his treatment of the concept during this time. The early poetry is of interest both because of its open concern with the otherworldly and because of its frank appreciation of the realia of the present world.

[23]

ABSTRACT

"Nabokov's Non-fiction as Reference Library: Igor, Ossian and Kinbote"

by Priscilla Meyer

(Abstract of a paper delivered at the Annual National Meeting of AATSEEL, Chicago, December 1985)

In his non-fiction Nabokov provides points of calibration for his fiction. Speak, Memory contains coded data for a reading of The Gift, the commentary to Onegin for Lolita, and the commentary to the Igor Tale for Pale Fire.

Kinbote's great-great-granddam Queen Yaruga is descended from Novgorod princesses, and Kinbote is descended from Igor, "the fruit of her amours with Hodinski," "a poet of genius said to have forged/... /a famous old Russian chanson de geste" (note to line 681). Yaruga is a rare Old Russian word for ravine, Nabokov says in the Igor commentary.

Nabokov deduces the authenticity of the Igor Tale from specific details like the word yaruga and from the internal evidence of artistic genius.

The political tendentiousness of the Igor bard is emphasized (note the repetition of "shadow"):

[24]

the tenacious shadow of Boyan is used by our bard for his own narrative purpose.

The protagonist of the Igor Tale is a shadow of an actual contemporary of our bard

who/.../has greatly magnified the campaign of 1185.

Kinbote is a scholar of early northern tales (note to line 12) (who "greatly magnifies" his own campaign) including "Angus MacBiarmid!s * incoherent transactions’". This alludes to James MacPherson's Ossian forgeries. Nabokov compares The Song and Ossian extensively in his commentary. In Pale Fire the national epics, one authentic and the other an eighteenth century forgery, are linked to address the method of transformation of historical reality into personal art. "MacDiarmid" is the pseudonym of С. M. Grieve (1892-1978), a Scottish nationalist poet who belonged to the Communist party and wrote two Hymns to Lenin (1952, 1935). Thus the scholarly inaccuracy and stylistic vagueness of Ossian is related to the alcoholic MacDiarmid's confused politics and misguided nationalist motives. Kinbote, then, on the one hand parodies "political" tendentiousness and on the other, Nabokov’s own pursuit: tracing northern legends and their interconnections, Nabokov seeks out the origins of his own personal fate in history. One such earliest point is the day on which Igor set out on his campaign: April 23rd, Nabokov's birthday.

Wesleyan University

Middletown, CT.

[25]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

[Material for this section should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov's works will be to the most recent hardcover U.S. editions.]

A Note on Nabokov's Gogol

Readers of The Nabokovian may be unaware that Nabokov's critical biography of Gogol, originally published by New Directions in 1944, now exists in three slightly different redactions (1944, 1961, 1973). The "corrected edition" (New Directions, 1961) makes a number of changes in what are obvious misprints. Certain passages have been deleted, e.g., a passage describing Derzhavin's visit to Pushkin's school (p. 8) and a parenthetical remark about Delvig's verse (p. 27). Nabokov has commented on these passages in his E.O. commentary, II, 314. Several changes have been made in the "nightmare index" (Nabokov's own expression, ibid.), but it remains as nightmarish as before. For reasons unclear to me the frontspiece portrait of Gogol has been deleted in the 1961 ed. and is also absent in the most recent 1973 ed. (although two references to it are made in all three editions, pp. 7-8, 155). A different portrait of Gogol

[26]

(with one of his eyes stretched over onto the spine of the book) appears on the paperback cover of the 1961 ed.

The first two editions are characterized by a lot of game-playing with letters (in particular sibilants); e.g., the critic Pisarev is deliberately misspelled Pissarev and the word brichka is spelled britzka. Other examples are too numerous to mention, but Nabokov obviously considered these misspellings inherent in the artistic structure of the book. In a letter to Edmund Wilson at the time Nikolai Gogol was first published he wrote that "its brilliancy is due to a dewy multitude of charming little solecisms" (Nabokov/Wilson Letters), p. 139).

Nabokov never seemed satisfied with his Gogol book and made a number of disparaging references to it in years subsequent to its 1944 publication. For example, this comment in a 1969 interview:

He [Gogol] would have been appalled by my novels and denounced as vicious the innocent,

and rather superficial, little sketch of his life that I produced twenty-five years ago. Much more

successful, because based on longer and deeper research, was the life of

Chernyshevski (in my novel The Gift).

(Strong Opinions, p. 156)

In his notes to the E.O. translation he described his Nikolai Gogol as "a rather frivolous little book with a nightmare index (for which I am not responsible) and an unscholar-

[27]

ly, though well-meant hodgepodge of transliteration systems (for which I am)" (II, 314). In light of these remarks it is not surprising that the author reworked the book slightly for its final edition, published in London by Weidenfeld and Nicolson in 1973. What is surprising is that this is not termed a "corrected" or "revised" edition, although some telling changes have been made. It is significant that the spelling of the title has been altered (Gogol's first name is now spelled with a y), as if to suggest that in a few respects this is a different book. Here are examples of changes in the text: (1) The word entrails changes to liver ("Pushkin, with a bullet in his liver," p. 2). (2) "Alice-in- the-Looking-Glass" changes to "through-the-Looking-Glass" (p.11). This minor change leads to a misprint when the following line is reset: "the oldest Russian in Russia" (should read "the oddest Russian in Russia," p. 12). (3) In the celebrated treatment of poshlust' one sentence is deleted: "The absence of a particular expression in the vocabulary of a nation does not necessarily coincide with the absence of the corresponding notion but it certainly impairs the fullness and readiness of the latter’s perception" (p. 63). (4) Footnotes are added to explain literary allusions (pp. 71, 78 — and on p.144 a footnote is altered slightly). (5) The following sentence is deleted from the Chronology (Winter 1836-1837): "Browning's door is preserved in the library of Wellesley College."

The above changes are, admittedly, minor. More significant is the standardization of the "unscholarly transliteration system" and the

[28]

therapy performed on the insane index. In the 1973 ed. a consistent system of transliteration has been adopted, although certain "typos" remain (e.g., the superfluous sibilant that wormed its way into the writer Veresaev's name remains there in all three editions--pp. 155, 159, 170). In this, his final redaction, Nabokov has chosen to make the index sane and traditional. Most of the game playing is gone, as are the madly gambolling minor literary characters. The joking reference to the publisher of the book ("James Laughlin, 151ff.") is missing, and even the name of the hated critic is spelled correctly (Pisarev).

A number of questions arise in connection with the appearance of the 1973 ed.: (1) Does the sanitization of the index change the complexion of the book in any essential way? (2) Why did Nabokov not incorporate these final changes into the American ed. of the work (New Directions continues to publish the 1961 "corrected edition")? In a reply to an inquiry letter that I sent to the London publisher, Vera Nabokov provides an answer:

The reason why the corrections were not transferred from the British ed. to the

New Directions ed. is, as my husband says in a letter, that he had neither time

nor inclination to go back to Nikolay Gogol. … The American index has been

replaced by a new one approved by my husband.

(letter of 12 April 1985)

(3) Since the revision of the index is significant, who was responsible for it originally (see the citation above, in which Nabokov denies responsibility for it)?

[29]

Anyone wishing to compare the three editions of the book can do so with relative ease since the typesetting and pages are essentially the same. James Laughlin of New Directions, who knew Nabokov personally and who first published the book in 1944, has been helpful in answering several of my questions. For example, I have always wondered about what I assumed was a fictitious dialogue between author and publisher in the Commentaries chapter (pp. 151-55). To what extent is this dialogue based on a real conversation? Mr. Laughlin confirms that he owned a lodge in the Wasatch Mountains of Utah and that the Nabokov family stayed with him there. See the picture of the Nabokovs in Utah and an account of an adventure that J. L. and Nabokov had in the mountains while hunting a rare butterfly (Paris Review, #90, p. 137—the date given for this picture, 1965, is obviously incorrect). Mr. Laughlin (letter of 30 April 1985) also says that Nabokov did indeed suggest a huge nose for the cover of the book (see Nikolai Gogol, p. 154).

In an article to be published in 1986 by The Journal of Modern Literature (Temple University) , I argue that this "critical biography" of Gogol (certainly one of the strangest biographies in the annals of world literature) is akin in many respects to a Nabokov fiction. I also assert that the narrator is a proxy figure (a "Nabokov") and that the semi-fictional nature of the work is complemented by the wild index of the first two redactions. I presented a shortened version of this article at the AATSEEL conference in Chicago (Dec. 1985). In her previously cited letter, incid-

[30]

entally, Mrs. Nabokov denies that the book is a kind of semi-fiction:

If you are planning to treat the book as part fictional, you may be

thinking of some other book, and not of Nabokov's Nikolay Gogol.

— Robert Bowie, Miami University

Subsidunt montes et iuga celsa ruunt (Ada 355)

With this quotation, the fourth line of Seneca's De Qualitate Temporis, Nabokov alludes to the Stoic theory of the periodic destruction and creation of everything in the universe. Rivers and Walker ("Notes to Vivian Darkbloom’s 'Notes to Ada’," Nabokov's Fifth Arc, pp. 289-90) point out that the line reflects some of the major themes of Ada — "the passage of time, the mutability of experience, and the threat of death and annihilation"—, but the allusion's significance in its immediate context, the rise and fall of the Villa Venus Club, also deserves some comment.

The notion of an eternal cycle of destruction and creation is reflected in the events described in pp. 347ff.: beginning with the accidental death of David van Veen's daughter, there arises a "momentum of disaster" (p. 347) which eventually overtakes Eric, who is unable to "escape a freakish fate: a fate strangely similar to his mother's" (the recurrence of the unusual mode of death itself demonstrates the cyclical nature of experience). Out of Eric's death, however, comes

[31]

the physical creation, of his Villa Venus project by his grandfather. But this too collapses in time amid "fires and earthquakes" (p. 356).

The cyclical pattern is also apparent in the incidental chronological details. David's daughter is killed in 1869 and in 1875 all one hundred "floramors" are opened. Fifteen years later, 1890 is described as "the greatest year in the annals of Villa Venus" (p. 352), but by 1905, fifteen years after the high point, deterioration has set in. By 1910, the destruction is almost complete (p. 356). Thus the rise and fall of the Club takes place over a period of about 40 years, bisected by the acme of 1890.

The description of the Villa Venus Club seems intended to recall the atmosphere and lifestyle of ancient Pompeii, a city also destroyed by "fires and earthquakes" when Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D. The Pompeians appear to have enjoyed an unusual degree of sexual freedom, but the city graffiti also reflect an acute, even brooding, awareness of the proximity of death. The tutelary deity of the city was Venus Pompeiana, who is represented on many excavated artifacts, as Nabokov was no doubt aware: Alfred Appel testifies to his familiarity with "the mosaics of Pompeii" ("Remembering Nabokov," Vladimir Nabokov: A Tribute, p. 12).

At the beginning of the novel, Ada refers to the Stabian flower girl (an allusion to the famous mural from Stabiae, a town destroyed along with Pompeii) and Van calls her "Pompei-

[32]

anella" (little Pompeiana) in reply. Not only the Villa Venus, then, but also the relationship between Van and Ada is, so to speak, "Pompeian," in the sense that it goes beyond the bounds of commonplace morality and behavior and can only be fulfilled in special places where normal restrictions do not apply. Pompeii, nestling on the seacoast, was just such a place in the Roman context. Also, like Pompeii, the relationship is ephemeral; by the end of the novel we realize that Van and Ada are already dead.

— David H. J. Larmour, University of Illinois

The Bohemian Sea and Other Shores

1.

The mention of the "Bohemian Sea, at Tempest Point" and of "Percival Blake" in Pnin' s Chapter Four (p. 86) is the tip of a submerged series of interlocked English literary allusions recruited to demonstrate Victor Wind's precocious erudition. The "coast of the Bohemian Sea" is one of the famous instances of Shakespeare's being at odds with geography: in Winter's Tale, Antigonus says "our ship hath touched upon the deserts of Bohemia" (iii.3), which is, of course, impossible since Bohemia is strictly inland on Terra. The "Tempest Point" is certainly a pointer of Shakespeare's next play (note by Charles Nicol, "Pnin's History," Novel, 4 [1971]: 3).

[33]

Sterne elaborated upon this curious error in Tristram Shandy, in the episode where Corporal Trim is trying hopelessly to tell Uncle Toby the story of the "King of Bohemia and his seven castles" (VIII, ch. 9). He never manages to get beyond the preliminaries, however, for the pedantic Uncle interrupts him each time he tries to proceed with his tale. One of Toby's comical interpolations occurs in the following environment:

The King of Bohemia...was unfortunate, as thus — That taking great pleasure and

delight in navigation and all sorts of sea affairs — and there happening throughout

the whole kingdom of Bohemia to be no seaport town whatever—How the deuce should there —Trim? cried mу uncle Toby: for Bohemia being totally

inland, it could have happened no otherwise — It might, said Tom, if it pleased God —Му uncle Toby never spoke of the being and natural attributes of God, but with diffidence

and hesitation —— I believe not, replied my uncle Toby, after some pause — for being inland, as I said, and

having Silesia and Moravia to the east; Lusatia and Upper Saxony to the north; Franconia

to the west; Bavaria to the south: Bohemia could not have been propelled to the sea without

ceasing to be Bohemia — nor could the sea, on the other hand, have come up to Bohemia,

without overflowing a great part of Germany ...

[34]

And in his "Scandal in Bohemia" (1892), Conan Doyle picks up Trim's unfinished tale and turns it into a detective story (about the King of Bohemia in a delicate situation, rescued by Holmes). The real king of Bohemia in those days was Franz Josef von Hapsburg, "the Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary"—a fitting title for Victor's imaginary father the king whose besieged palace must be in Maribor, on the traffic junction connecting Austria, Croatia, Italy, and Hungary. The narrator, who lends Victor this literary fantasy, says that the "omnibus edition of Sherlock Holmes" has been pursuing him for years (p. 190).

Percival Blake, scheduled to visit Victor's predormant fancy in a powerful motorboat (to save the fleeing King who is supposed to meet him at Tempest Point) is also a crossbreed of at least two literary characters. A courageous Englishman Percy Blakeney conceals his identity and invariably outwits his opponents in Scarlet Pimpernel, a novel by Emmuska Orczy that Victor is said to have read (p. 86). The Perceval of an old European legend graces the title of an epic poem by Chretien de Troyes (12th c.) as well as of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival (13th c.), but Victor must have remembered him from Malory’s adaptation of the Arthurian tales where Percivale is the son of King Pellinore. In The Real Life of Sebastian Knight (which Victor theoretically may have read), a "certain commercial traveller Percival Q." makes a brief appearance on page 96.

[35]

Indeed, Victor is so incredibly well versed in English letters for his age (Malory, Shakespeare, Sterne, Doyle, Orczy, perhaps Nabokov) that it is particularly bathetic, by contrast, that Pnin, who a priori imagines Victor to be an "average American lad," should have bought him a soccer ball and a shallow novelette by Jack London.

An exactly opposite (to the Bohemian Sea affair) geographical freak is mentioned a few pages further, in one of those deceptively non-referential, ostensibly noncommittal digressions that inform, to a degree, Nabokov's English fiction. A detailed description of Victor's school, St. Bartholomew, includes the story of the Saint's martyrdom; his relics were reportedly floated, in a lead coffin, from Albanopolis to the island of Lipari, near Sicily (p. 93). Just as the securely landlocked Bohemia could not possibly have access to the sea unless it pleased Shakespeare, the entirely inland Caspian Sea cannot be a gateway to the Mediterranean. The matter is thus neatly reversed iniand-out, as it were.

2.

In his commentary to Canto Two of Eugene Onegin, Nabokov traces the literary name Lensi to Heraskov's Rossiada and to Feigned Infidelity, a comedy by Griboedov and Gendre who transfigured into Russian Barthe1s original Les Fausses infidélités. Nabokov capsulizes its plot thus: "Lenski, a merry young man, and a friend of his make fun of an old fop by having their sweethearts feign love for him"

[36]

(ii.228). Factual mistakes are extremely hard to come by in this work, but this is one of those rarities. Actually, the plot of that unprepossessing hut nicely written little play moves in the opposite direction: it is Eledina and her sister Liza who dupe, out of vexed boredom, their respective beaux into thinking that each lady is in love with Bliostov, a notoriously dashing, if somewhat worn, dandy. The naive intrigue's aim is to make Lenski and Roslavlev propose, which they do. No one seems to have noticed that Pushkin endowed his Lenski with the snivelish attributes of Griboedov's Roslavlev (of whom Griboedov's Lenski says that he is "ridiculous in his tendresse, amusing in his jealousy") while some of the earlier Lenski's qualities — flippant arrogance, bland skepticism, assumed coolness — went to Onegin.

3.

To follow up Mr. Shapiro's note on the drowned Dr. Sineokov of Invitation to a Beheading (Nabokovian 15): those livid names crop up in Nabokov's fiction since the mid-thirties with some regularity. The bereft artist of "Ultima Thule" bears the name of Sineusov (in the English version, A. I. Falter calls him "Moustache-Bleue"). Then there is that farcical librarian Sinepuzov ("A surname, meaning 'blue belly', which affects a Russian imagination in much the same way as Winter-bottom does an English one") lurking in "Conversation Piece, 1945." And in Shade's poem, the "college astronomer Starover Blue" is mentioned twice (11. 189, 627). In his note

[37]

to the latter, Kinbote submits that the tempting "star over the blue" is deceptive; that starover in Russian means "old believer"; that his original Russian name was Sinyavin (Blue); and that he married a Stella Lazarchik (Star Azure), the two making the nearly perfect astronymous Gemini. [And this brings to mind Bend Sinister's Dr. Azureus - Ch. Nicol]

Ingenious as Mr. Shapiro’s theory might be, Nabokov was not in the habit of plunging a real person into an invented milieu, unless it served a very special purpose similar to the one which made Pushkin introduce his friend Viazemski to Tatiana at the Prince's aunt's in Canto Seven of Eugene Onegin. There may be another source for that spree of blue surnames. According to Andrew Field, in 1934 a friend of Nabokov

provided him with a list of the names of aristocratic Russian families which had

died out. This list with names like Cherdyntsev, Barbashin, Kachurin, Sineusov,

Revshin...served to furnish the names of characters for almost all the rest of

Nabokov's émigré writing.

(Nabokov: His Life in Part, p. 200).

Did Nabokov use that initial Sineusov as a blueprint for the rest of his Blues? The formula is conveniently productive and not unprecedented in Russian literature: Chekhov has somewhere a Sinerylov (Blue Snout), and Zoshchenko's collection of short stories was entitled Tales of Nazar Ilyich, Mr. Sinebriuhov (Blue Paunch).

— Gene Barabtarlo, The University of Missouri, Columbia

[38]

Nabokov’s Horological Hearts

Nabokov repeatedly returns to the heart and heartbeat as images of chronological time and its succession or measurement (or in the case of the heart attack its interruption or abolition—thus in Ada Van Veen simulates a heart attack when technical problems interrupt a lecture he is giving on Time [p. 548]). Of course, the heart, the "ticker," is conventionally associated with time through its symbolic identification with the clock: thus a pocket watch is for Nabokov "a spare heart" (VNRN 10, p. 43); in The Defense Luzhin is tempted "to stop the clock of life" (p. 214) and the ticking of his actual clock is described as a series of "tiny heartbeats" (p. 185). It is instructive to consider some of the ways in which Nabokov exploits this association.

One way is by the juxtaposition of failed hearts and stopped clocks. On the opening page of Glory we learn that Martin Edelweiss' grandfather died

holding in the palm of his hand his beloved gold watch, whose lid was like a

little golden mirror. Apoplexy overtook him during this timely gesture and

according to family legend, the hands stopped at the same moment as his heart.

Thus death puts an end to time. Again, in Bend Sinister, when Adam Krug is in Dr. Azureus' study on the night of his wife's death, he notices that Azureus' clock has

[39]

stopped at a quarter past six. Krug calculated rapidly, and the blackness

inside him sucked at his heart. (pp. 51-52)

The same association appears in The Eye. Preparing for his suicide attempt, Smurov remarks that the act of writing a will would be "just as absurd as winding up one's watch, since, together with the man, the whole world is destroyed" (p. 28). A few lines later Smurov "removed [his] wrist watch and kept dashing it against the floor until it stopped. "

In another, shorter piece from the thirties , "Breaking the News," the connection is made less explicitly. Prior to hearing of the death of her son, Misha, in Paris, Eugenia Isakovna is shopping in Berlin. A man she sees reminds her of a former acquaintance "who had died alone, in a sleeping-car, of heart failure, so sad, and as she went by a watchmaker's she remembered that it was time to call for Misha's wristwatch, which he had broken in Paris" (A Russian Beauty, p. 40). Eugenia Isakovna may be reminded of the wrist-watch by the thought of her friend's heart failure, but for the reader (who already knows of Misha's death) the broken watch has a more obvious and immediate significance.

Another way in which Nabokov makes use of the conventional heart/clock association is by transferring the properties of the one to the other. The hero of "Lik" suffers from severe heart trouble. Afraid to lie down for fear of palpitations after his first attack in the

[40]

story, he looks out of his window at the sea and has the impression that

this ample, viscously glistening space, with only a membrane of moonlight

stretched tight across its surface, was akin to the equally taut vessel of his

drumming heart, and, like it, was agonizingly bare, with nothing to separate

it from the sky....He glanced at the expensive watch on his wrist and noticed

with a pang that he had lost the crystal; yes, his cuff had brushed against a

stone parapet as he had stumbled uphill a while ago. The watch was still

alive, defenseless and naked, like a live organ exposed by the surgeon's knife.

(Tyrants Destroyed, p. 79)

The exposed watch-face serves clearly to suggest Lik's anxiety concerning his heart and what he feels to be the undeserved precariousness of his life and the imminence of approaching death. In this case there is a triple association—between Lik's heart, the "bare" surface of the sea, and his "naked" watch. A less elaborate use is made of this device in Look at the Harlequins! where, after striking an old (in both senses of the word) acquaintance, the aging narrator remarks: "I listened to my wristwatch. It ticked like mad" (p. 219). The somatic experience is projected outwards onto the watch.

It is of course the rhythmical nature of the heart's activity that is responsible for its horological aspect; the heart becomes a sort of personal and organic chronometer.

[41]

Thus, during Pnin's childhood fever, when he is examined by the family doctor, "a race was run between the doctor's fat golden watch and Timofey's pulse (an easy winner)" (p. 22). A similar association informs the opening lines of Speak, Memory with its image of man rushing towards death "at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour," and Nabokov's later description of his governess' bedroom as "some twenty heartbeats' distance from" his own (p. 109). The logical extension of this heart/ clock association is a complete identification between the two. Such an identification is suggested in "Tyrants Destroyed" when the narrator reports that the clocks of the state are soon to be set by the tyrant's heartbeat, "so that his pulse, in the most literal sense, will become a basic unit of time" (Tyrants Destroyed, p. 20). The twin tyrannies of politics and time are fused here to form a single symbol of oppression.

Of all Nabokov's characters it is appropriate that time-philosopher Van Veen should be most aware of this chronometric aspect of the heart. He reports that he

made the mistake one night in 1920 of calculating the maximum number

of his heart's remaining beats (allowing for another half-century), and now

the preposterous hurry of the countdown irritated him and increased the

rate at which he could hear himself dying.

(Ada, pp. 569-70)

This explains the predilection of a number of Nabokov characters (Van Veen, Pnin, Vadim of

[42]

Look at the Harlequins!, Dreyer of King, Queen, Knave) for sleeping on their right or "non-cardinal" side—so as not to be reminded of the lapse of time, so as not to hear themselves dying. In this connection it is worth mentioning Humbert Humbert, who complains of tachycardia (Lolita, p. 27). Humbert's problem is that time is going too fast for him, hence his nympholepsy as a way of arresting time, of escaping to that "island of enchanted time" inhabited by the nymphet.

If the regular, rhythmic beating of the heart serves as a metaphor for the rhythmic passage of chronological time, then the lapse or break in the heart's rhythm corresponds in Nabokov's imagery to the "fissure in time," the timeless moment. In Speak, Memory Nabokov records how his first poem was born in "not so much a fraction of time as a fissure in it, a missed heartbeat" (p. 217). This is the kind of time, or non-time, in which Cincinnatus lives in his imagination in Invitation to a Beheading: "that second, that syncope... the pause, the hiatus, when the heart is like a feather" (p. 53). In Lolita, when Humbert picks up his nymphet from Camp Q after a month away from her, he describes his first impression of her as occurring in "a very narrow human interval between two tiger heartbeats" (p. 113). And in Ada Demon Veen's "heart missed a beat and never regretted the lovely loss" when he sees Marina return to the stage in a play between two scenes of which he has just possessed her, his missed heartbeat mimicking or echoing that moment of erotic bliss, that "brief abyss of absolute reality between two bogus fulgurations of fabricated

[43]

life" (p. 12). Later in the novel, of course, Van Veen will elevate this "Tender Interval" between two rhythmic beats to something approaching the true essence of time, lending it his name—"Veen’s Hollow"—in the manner of a scientific discoverer or explorer (p. 538, 549). This may help to explain the curious proneness of Nabokov's characters to palpitations , double systoles, and other irregularities of heartbeat. Adam Krug speaks of "letting this or that moment rest and breathe in peace. Taming time. Giving her pulse respite" (Bend Sinister, p. 13) as a way of "immobilizing” time. "In this sense human life is not a pulsating heart but the missed heartbeat" (Strong Opinions, p. 186).

— Robert Grossmith, University of Keele, Keele, England

[44]

Lost and Found Columns: Some New Nabokov Works

by Brian Boyd

Over the last few years I have from time to time been scouring for more Nabokov works in newspapers and periodicals, especially in Helsinki, Prague, Berlin, Paris, London, New York and Stanford, as well as in the Nabokov archives. The results are not complete, but it is time to make available what has been discovered so far.

The following additions and corrections to Andrew Field's Nabokov: A. Bibliography. Are arranged chronologically, with their places in Field's ordering system indicated. A letter after the Field number usually indicates a new entry, occasionally a relocation.

All details have been taken from originals unless otherwise indicated. Transliterations follow the method Nabokov decided on in his last years. First lines of poems are recorded immediately after poem titles.

This list is a stopgap: its contents will be included in Michael Juliar's imminent Nabokov primary bibliography, much superior to Field's in accuracy, thoroughness, fullness of bibliographical detail and attention to the user's needs.

University of Auckland

[45]

Poem in Russian. "Yaltinskiy mol" ("Yalta Pier") ("V tu noch' prisnilos' mne, chto ya na dne morskom," "That night I dreamt I was on the sea floor"). Yaltinskiy golos. Yalta. 8 September 1918, pp. 3-4.

(Field 0408A)

Poem in Russian. "Bahchisarayskiy fontan (Pamyati Pushkina)" ("The Fountain of Bahchisaray (In Memory of Pushkin)") ("On zdes' odnazhdy byl, voda edva zhurchit," "He once was here, the water hardly murmurs"). Yaltinskiy golos. Yalta. 15 September 1918, p. 3 .

(Field 0408 B)

Poem in Russian. "Vecher tih" ("The Night is Quiet") ("Vecher tih. Ya zhdu otveta," "The night is quiet. I await an answer"). Yaltinskiy golos. Yalta. 13 October 1918, p. 2. (Field 0408C)

Poem in Russian. "Les" ("The Forest") ("Doroga v temnote pechalitsya lesnaya," "The forest road in darkness grieves"). Rul’. Berlin. 27 November 1920 (#10), p. 3.

(Field 0411A; delete 0444)

Story in Russian. "Nezhit"' ("Sprite"). Rul’. Berlin. 7 January 1921 (#43), p. 3.

(Field: before 0906)

Poems in Russian. "Tihaya osen'" ("Quiet Autumn") ("U samogo kryl'tsa obryzgala mne plechi," "On the porch itself bespattered my shoulders") and "Byl krupnyy dozhd'. Lazur' i shire i zhivey" ("A heavy rain has fallen. The azure is broader and more alive"). Rul’. Berlin. 20 February 1921 (#80), p. 2.

[46]

(Field 0416 lists only the first poem.)

Poems in Russian. "Kаk vesnoyu moy sever prizyven!" ("How alluring my North is in the Spring!") and "Bezvozratnaya, vechno-rodnaya" ("Lost forever, forever my own"). Rul’. Berlin. 27 March 1921 (#109), p. 5.

(Field 0416A; delete 0410 and 0467. The poems appear under the heading "Rodina" ("Native Land"), which field refers to in entry 0467; this was the newspaper's group title for two separate poems written in different years and untitled in Nabokov's manuscripts.)

Poems in Russian. "Gde ty, aprelya veterok" ("Where are you, little wind of April") and "Ya bez slyoz ne mogu" ("I can’t look at you, Spring, without tears"). Rul’. Berlin. 12 April 1921 (#121), p. 2.

(Field 0417. These are two separate poems, again imder a group title the newspaper supplied: "Vesna" ("Spring").)

Poem in Russian. "Bezhentsy" ("The Exiles") ("Ya ob'ezdil, о Bozhe, tvoy mir," "I traveled, God, around your world") Rul’. Berlin. 18 June 1921 (#176), p. 7.

(Field 0422 gives "May ?" date; Kuzmanovich incorrectly supplies "May 20" in Nabokovian 13, p. 37. Delete Field 0423. Field notes the poem was reprinted in Antologiya satiry i yumora, 1922; it was also reprinted in Aleksandr Voloshin, ed., Vechera pod zelyonoy lampoy, Berlin: Hudozhestvennaya Literatura, n. d. (1922), p. 66.)

Poem in Russian. "My stolpilis' v tumannoy tserkovenke" ("In the dim little church we

[47]

have crowded"). Rul’. Berlin. 29 July 1921 (#211), p. 2.

(Field 0424 lists as 29 June.)

Poem in Russian. "Detstvo" ("Childhood") ("Pri zvukah nekogda podslushannyh minuvshim," "At sounds once overheard by the past"). Grani. Berlin. No. 1. 1922. Pp. 95-100.

(Field 0439A; actually published December 1921.)

Poem in Russian. "V zvernitse" ("In the Menagerie") ("Tut ne zveri, a bogi zhivut," "Not beasts, but gods live here") Segodnya. Riga. 3 October 1922 (#222), p. 2.

(Field 0456A)

Poem in Russian. "Glaza" ("Eyes") ("Pod tonkoyu lunoy, v strane dalyokoy, drevney," "Under a slender moon, in a far-off, ancient land"). Segodnya. Riga. 18 November 1922 (#261), p. 4.

(Field 0458A)

Poem in Russian. "Pegas" ("Pegasus") ("Glyadi von tarn, na toy skale,— Pegas!" "Look there, upon that rock,— Pegasus!"). Segodnya. Riga. 6 December 1922 (#275), p. 2.

(Field 0459A)

Poem in Russian. "Feina doch' utonula v rosinke" ("A fairy’s daughter drowned in dew").

(Field 0120 lists a title "Feina doch'" for this poem from Nabokov's collection Gorniy put’ (published January 1923), but the poem appears without title.)

[48]

Poems in Russian. "Zhemchug" ("The Pearl") ("Poslannyy mudreyshim vlastelinom," "Sent by the wisest potentate"), "Cherez veka" ("A Century Later") (V kakom rayu vpervye prozhurchali," "In what heaven first did purl"), and "Uzor" ("The Pattern") ("Den’ za dnyom, tsvetushchiy i letuchiy," "Day after day, flowering and flying"). A’lmanah Mednyy Vsadnik. Berlin. Book 1 (n. d.) , pp. 267-69.

(Field 0466A; apparently published January 1923.)

Poem in Russian. "Vlastelin" ("The Ruler") ("Ya Indiey nevedomoy vladeyu," "I rule an unknown India”). Segodnya. Riga. 8 April 1923 (#72), p. 5.

(Field 0469A)

Poem in Russian. "Na ozere" ("On the Lake") ("V glazah ryabilo ot rez'by," "We were dazzled by the fretwork"). Segodnya. Riga. 22 April 1923 (#84), p. 5.

(Field 0469B)

Poems in Russian. "I v Bozhiy ray prishedshie s zemli" ("And those who've come from earth to Paradise") and "Iz mira upolzli — i noyut na lune" ("From the earth they crawled—and on the moon they whine"). Zhar-Ptitsa. Berlin. No. 11. 1923. p. 32.

(Field 0481 lists only the first of these two distinct poems.)

Poem in Russian. "Shekspir" ("Shakespeare") ("Sredi vel'mozh' vremyon Elizavety," "Among the grandees of Queen Bess's time"). Zhar-Ptitsa. Berlin. No. 12 (n. d.), p. 32.

[49]

(Field 0494A; delete 0528. Published by 6 July 1924.)

Story in Russian. "Kartofel'nyy el'f" ("The Potato Elf"). Russkoe Eho. Berlin. 8 June 1924 (#44), pp. 6-7; 15 June 1924 (#45), pp. 5-7; 22 June 1924 (#46), p. 8; 29 June 1924 (#47), pp. 6-7; 6 July 1924 (#48), p. 12.

(Field 0910 missed the final installment.)

Poem in Russian. "Otdalas' neobychayno" ("resounded strangely"). Segodnya. Riga. 24 September 1924 (#217), p. 4.

(Field 0502A. Printed without the title, "Royal1" ("The Grand Piano"), which flows into the first sentence of the poem and whose absence in this first printing therefore mars the poem's sense. Reprinted, with title, in Gazeta Bala Pressy, 14 February 1926, Field 0530.)

Poem in Russian. "Kostyor" ("The Bonfire") ("Na sumrachnoy chuzhbine, v chashe," "In a foreign twilight, in a thicket"). Vestnik glavnogo pravleniya obshchestva Gallipoliytsev. Belgrade. 1924. p. 7.

(Field Q508A; delete 0482, which has incorrect title, place and date for the Vestnik.)

Poem in Russian. "Demon" ("The Demon"). Russkoe Eho. Berlin. 4 January 1925 (#74).

(Field 0509A. Unlocated; cited from the highly reliable publications index in Volya Rossii, 1925:2, p. 5.)

Poem in Russian. "Plevitskoy" ("To Plevitskaya"). Russkoe Eho. Berlin. 11 January 1925 (#75).

[50]

(Field 0509B. Unlocated; cited Volya Rossii 1925:2, p. 5.)

Excerpt from Russian novel Mashen' ka (Mary), "Otryvok iz romana ’Mashen'ka'.” Vozrozhdenie. Paris. 2 March 1926 (#273), pp. 2-3.

(Add to Field 0651)

Poem in Russian. "Pustyak, nazvan'e machty, plan,— i sledom" ("A trifle, the name of a mast, a plan"). Zveno. Paris. 4 July 1926 (#179), p. 7.

(Field 0534 cannot decide between 3, 3-4 or 4 July.)

Poem in Russian. "Tihiy shum" ("Soft Sound") ("Kogda v primorskom gorodke," "When in a little seaside town"). Rul’. Berlin. 10 June 1926 (#1676), p. 4.

(Field 0531 records wrong date; printed with a record of the poem's reception when Nabokov read it as part of "Den' russkoy kultury" (Russian Culture Day"), the title of the article under which the poem appears.)

Translation into Russian of Alfred de Musset, "La Nuit de mai." "Mayskaya noch'." Rul’ . Berlin. 20 November 1927 (#2122), pp. 2-3.

(Field 1282A; Field 1283 incorrectly groups this with Nabokov’s translation of Musset's "La Nuit de decembre" at 1283, for which details are otherwise correct.)

Poem in Russian. "Razgovor" ("Conversation") ("Legko mne na chuzhbine zhit'," "I can easily live abroad"). Rossiya. Paris. 14 April 1928 (#34), p. 2.

[51]

(Field 0557 records wrong newspaper.)

Review in Russian. "Vystavka M. Nahman-Achariya" ("M. Nahman-Achariya Exhibition"). Rul’. Berlin. 1 November 1928 (#2413), p. 4.

(Field 1129 records wrong date.)

Review in Russian of Aleksey Remizov, Zvezda nadzvezdnaya (The Suprasidereal Star). Rul’. Berlin. 14 November 1928 (#2424), p.4.

(Field 1130 records wrong date.)

Poem in Russian. "Kinematograf" ("The Cinema”) ("Lyublyu ya svetovye balagany," "I love the colored shows"). Rul’. Berlin. 25 November 1928 (#2433), p. 2.

(Field 0551 records wrong date.)

Review in Russian of Sovremennye Zapiski XXXVII. Rul’. Berlin. 30 January 1929 (#2486), p. 2.

(Field 1132 records wrong date.)

Poem in Russian. "Predstavlenie" ("The Presentation") (Eshchyo temno. V orkestre stesneny," "Still dark. In the orchestra are cramped"). Rossiya i Slavyanstvo. Paris. 25 October 1930 (#100), p. 3.

(Field 0573; delete 0574, which merely garbles additional information that should have appeared in his 0573.)

Excerpt from Russian novel Podvig (Glory). "Alla." Segodnya. Riga. 5 February 1931 (#36), p. 6.

(Add to Field 0725)

[52]

Review in Russian of Boris Poplavsky, Flagi (Flags). Rul’. Berlin. 11 March 1931 (#3128), p. 5.

(Field 1143 records wrong date.)

Excerpt from Russian novel Kamera obskura. "Otryvok iz romana." Russkiy invalid. Paris. 22 May 1931 (#17).

(Add to Field 0704)

Poem in Russian. "Sam treugol’nyy, dvukrylyy, beznogiy" ("He was triangular, two-winged, and legless"). Poslednie novosti. Paris. 8 September 1932 (#4187), p. 3.

(Field 0582 records wrong date and issue number.)

Story in Russian. "Hvat" ("The Dashing Fellow"). Segodnya. Riga. 2 October 1932 (#273), p. 4; 4 October 1932 (#275), p. 2.

(Field 0956B; delete 0972.)

Excerpt from Russian novel Dar (The Gift). "Smert' Aleksandra Yakovlevicha" ("The Death of Alexander Yakovlevich"). Poslednie novosti. 24 April 1938 (#6238), p. 2.

(Add to Field 0734)

Letter to the Editor. "Protest protiv vtorzheniya v Finlandivu" ("Protest against the invasion of Finland"). Poslednie novosti. Paris. 31 December 1939 (#6852), p. 2.

(Field 1310A. A group letter signed by Gippius, Teffi, Berdyaev, Bunin, Zaitsev, Aldanov, Merezhkovsky, Remizov, Rachmaninov and Sirin (Nabokov).)

[53]

Interview in Russian with Nikolay All. "V.V. Sirin-Nabokov v N'yu-Iorke chuvstvuet sebya ‘svoim'" ("V. V. Sirin-Nabokov feels himself 'at home’ in New York"). Novoe Ruskoe Slovo. New York. 23 June 1940, p. 3.

(Field 1311A; cited from dated clipping.)

Article in Russian. "Pamyati I.V. Gessena" ("In Memory of I.V. Gessen"). Novoe Russkoe Slovo. New York 31 March 1932 (#10,995), p. 2.

(Field 117 0A)

Interview in Russian with Nathalie Shahovskoy. Voice of America. 14 May 1958.

(Field 1314A. Radio interview.)

Interview with Patrick Watson and Lionel Trilling. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 November 1958?

(Field 1317A. Filmed in New York 26 November 1958; cited in unpublished correspondence between Nabokov and CBC.)

Interview remarks. Paul O'Neil. "'Lolita’ and the Lepidopterist: Author Nabokov is Awed by Sensation He Created." Life International, 13 April 1959, pp. 63-69.

(Field 1318B. Even after Lolita's American success Nabokov was considered too risqué for the home edition of Life.)

Interview remarks. Robert H. Boyle. "An Absence of Wood Nymphs." Sports Illustrated. 14 September 1959, pp. E5-E8.

(Field 1319A; change present 1319A (see VNRN 4, p. 42) to 1319B.)

[54]

Interview with Alan Pryce-Jones. ABC TV. 1 November 1959.

(Field 1320A. Television interview for the Book Man program, filmed 29 October 1959, broadcast on ITV Channel 9; cited in unpublished letter, Guy Verney to Nabokov, 30 October 1959.)

Interview with David Holmes. "Professor Vladimir Nabokov interviewed by David Holmes." BBC. 5 November 1959.

(Field 1320B. Radio Newsreel interview, broadcast on BBC Home and Overseas Service.)

Interview. Neue Illustrierte. Cologne, c. 24 January 1961.

(Field 1324A. Unlocated; cited from unpublished letters, Véra Nabokov to Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt, 19 and 31 January 1961.)

Interview with Gilles J. Daziano. Télé-Monte Carlo. 28 February 1961.

(Field 1324B; cited by United States Information Office's Centre culturel américain, Nice, in Nabokov archives.)

Interview remarks. Alberto Ongaro. "L’Amore Oggi: Visto dall’autore di Lolita." L'Europeo. 23 June 1966, pp. 28-33.

(Field 1347A)

Interview with Herr Schroeder-Jahn. 1966. (Field 1349A; German television interview, cited in unpublished letter, Véra Nabokov to Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt, 5 June 1966.)

Letter to the Editor. Le Figaro Littéraire. Paris. 2-8 December 1968 (#1178), p. 3.

[55]

(Field 1364A. Re invented Nabokov remarks in Figaro Littéraire, 11-17 November 1968 (#1175), p. 19.)

Letter to the Editor. Die Presse. Vienna. 23 May 1969, p. 4.

(Field 1368A; printed as part of article "Nabokov Contra Helwig," re bogus interview by Werner Helwig, Die Presse, 25 April 1969.)

Interview with Alden Whitman. "Nabokov, Near 71, Gets Gift for 70th." New York Times. 18 March 1970, p. 40.

(Field 1378B)

Letter to the Editor. "Nabokov and Wilson." New Statesman. London. 5 May 1972, pp. 597-98.

(Field 1388C; change present 1388C (see VNRN 4, p. 46) to 1388D, present 1388D, 1388E, 1388F, 1388G to 1388S, 1388T, 1388U and 1388W respectively.)

Chess problem. No. 1176. The Problemist. 9:17 (September 1972), p. 260.

(Field 1236B; solution and comments from readers, The Problemist, 9:19 (January 1973), p. 300.)

Letter to the Editor. "Aspersion Rejected." New Statesman. London. 22 December 1972, p. 945.

(Field 1388E)

Interview with Claude Jannoud. "Vladimir Nabokov le plus américain des écrivains russes." Le Figaro littéraire. Paris. 13 January 1973, pp. 13, 16.

[56]

(Field 1388F; listed in Field's Addenda, no. 1.)

Interview remarks. R.T. Kahn. "The Swiss Riviera Exposed." Holiday, January-February 1973, 50-55.

(Field 1388G)

Chess problem. No. C5550. The Problemist. 9:21 (May/June 1973), p. 326.

(Field 1236C; solution and readers' comments, The Problemist, 9:23 (September/October 1973), p. 363.)

Chess problem. No. S382. The Problemist. 9:22 (July/August 1973), p. 350.

(Field 1236D. This problem was modified by C. R. Flood, editor of The Problemist's self-mate section; solution and readers' comments, The Problemist, 9:24 (November-December 1973), p. 386; reprinted on winning 3rd prize in self-mate section, The Problemist, 9:31 (January /February 1975), p. 501.)

Interview with Roberto Cantini. "Nabokov Tra i Cigni de Montreux." Epoca. Milan. 7 October 1973, pp. 104-112.

(Field 1388H)

Acceptance Speech, National Medal for Literature. Publisher's Weekly Trade News, 15 April 1974.

(Field 13881. Reprinted in report by I.F.B., "Nabokov Gets the National Medal for Literature — By Proxy," Publisher's Weekly, 13 May 1974, p. 33, and in The Nabokovian, 15 (Fall 1985), p. 10.)

[57]

Letter to the Editor. Observer. London. 26 May 1974.

(Field 1388J)

Interview with Helga Chudacoff. "Schmetterling sind wie Menschen." Die Welt. 26 September 1974, Welt des Buches, p. Ill.

(Field 1388K)

Chess problem. No. S424. The Problemist, 9:29 (September/October 1974), p. 469.

(Field 1236E; solution and readers' comments, The Problemist, 9:31 (January/February 1975), p. 497.)

Interview with Bernard Safarik. Late 1974?

(Field 1388L. Swiss German television interview, filmed c. August 1974; cited from transcript in Nabokov archives, Montreux.)

Interview with Dieter Zimmer. Late. 1974?

(Field 1388M. Hessischer Rundfunk, Frankfurt, television interview, filmed 29 September 1974; cited from transcript in Nabokov archives, Montreux.)

Translation into English from Pushkin's "Ptichka" ("Little Bird") and note. William McGuire, ed., The Freud/Jung Letters. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press (Bollingen Series), 1974, p. 72n.

(Field 1303B)

Telegram cited in Carl Proffer's Letter to the Editor. New York Review of Books. 6 March 1975, p. 34.

(Field 1388N; telegram sent 30 December 1974 to Leningrad Union of Writers re Maramzin.)

[58]

Interview remarks. James Salter. "An Old Magician Named Nabokov Writes and Lives in Splendid Exile." People. 17 March 1975, pp. 60-64.

(Field 13880)

Interview with Bernard Pivot. Channel 2. Paris. 30 May 1975.

(Field 1388P. Live television interview for Pivot's "Apostrophes" series; cited in unpublished letter, Véra Nabokov to Marie Schebeko, 2 May 1975.)

Interview remarks. Sophie Lannes. "Portrait de Nabokov." L'Express. Paris. 30 June 6— July 1975, pp. 22-25.

(Field 1388Q)

Letter to the Editor. "Novelist as lepidopterist." New York Times. 27 July 1975, p. 46.

(Field 1388R; published as appendix to article by Paul Showers, "Signals from the Butterfly," pp. 10, 42-46.)

Reply to questionnaire. "Authors' Authors." New York Times Book Review. 5 December 1976, p. 4.

(Field 1388V)

Interview with Hugh A. Mulligan. "Interview with Nabokov." Ithaca Post, 30 January 1977, p. 17.

(Field 1388X)

Interview with Robert Robinson. "A Blush of Colour—'Nabokov in Montreux." The Listener. London. 24 March 1977, pp. 367, 369.

[59]

(Field 1388Y. From TV interview for BBC Book Programme, filmed 14 February 1977; reprinted in Peter Quennell, ed., Vladimir Nabokov: A Tribute (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979 and New York: William Morrow, 1980).)

Poem in Russian: "Kаk dolgo spit, a strunnyy Struve" ("How long he sleeps, о stringed Struve"). Novoe Russkоe Slovo. 7 August 1977, p. 5.

(Field 0650A; in article by Gleb Struve, "K smerti V.V. Nabokova," "On the death of V.V. Nabokov.")

Chess problem. Trinity Review. Cambridge, England. Summer 1977, p. 36.

(Field 1236F; possibly a reprint of an earlier problem.)

Translation by Djemma Bider of Russian poem "Kto menya povezyot?" "Who will drive me home?" New Yorker. 30 October 1978, p. 40.

(Field 0432A)

Translation by Joseph Brodsky of Russian poem "Otkuda priletel." "Demon." Kenyon Review. N.S. 1:1 (Winter 1979), 120.

(Field 0650B)

Interview with Mati Laansoo. "An Interview with Vladimir Nabokov for the CBC." Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter. No. 10 (Spring 1983), 39-48.

(Field 13882; interview conducted 20 March 1973.)