Download PDF of Number 11 (Fall 1983) Vladimir Nabokov Research Newsletter

THE VLADIMIR NABOKOV

RESEARCH NEWSLETTER

Number 11 Fall 1983

_______________________________________________

CONTENTS

News Items and Work in Progress

by Stephen Jan Parker 4

Nabokov Bibliography: Aspects of the Emigré Period

by Brian Boyd 16

Vladimir Nabokov: An Exhibition of Correspondence,

Photographs, First Editions, Butterflies ...

by Marilyn B. Kann 25

Abstract: Charles Nicol, "Who Wrote This Book?"

(MLA paper) 37

Abstract: Janet Gezari, "Nabokov's Poetry of Chess:

The Problems in Speak, Memory"

(MLA paper) 39

Abstract: D. Barton Johnson, "Text and Pre-Text in

Nabokov's Defense"

(paper) 40

Annotations & Queries By Charles Nicol

Contributors: Leszek Engelking, Jean-Louis Chevalier,

Julian Connolly, Charles Nicol 41

1982 Nabokov Bibliography by Stephen Jan Parker

Contributor: Paul Morgan 49

Reminder 64

Note on content:

This webpage contains the full content of the print version of Nabokovian Number 11, except for:

- The annual bibliography (because in the near future the secondary Nabokov bibliography will be encompassed, superseded, and made more efficiently searchable in the bibliography of this Nabokovian website, and the primary bibliography has long been superseded by Michael Juliar’s comprehensive online bibliography).

[4]

NEWS ITEMS AND WORKS IN PROGRESS

by Stephen Jan Parker

Subscription rates to the VNRN have remained steady for three years, as has the number of subscribers (ca. 250-260). During this period our expenses for supplies, postage, and printing have risen significantly, and each year our deficit has grown larger. We would like not to increase our rates, and continue to offer what one reader has termed "the best buy for the money that one can find." In order to do this we need to generate greater revenue through a healthy increase in subscriptions. Our readers' help in this regard is needed. Once again we urge you to ask your libraries to subscribe and to send us the names of persons and/or institutions that might be interested in joining the Society and obtaining the VNRN. Other suggestions for ways to increase revenue are welcome. (Is there perhaps a potential patron out there reading these words?)

*

The Vladimir Nabokov Society will hold its annual meetings in conjunction with both the MLA and AATSEEL conventions in New York City in December.

The Nabokov section at the MLA meeting is scheduled for Wednesday, December 28, 3:30 - 6:30 pm, Room 537, Hilton Hotel. The section, to be chaired by Beverly Clark and Phyllis Roth, has as its title, "Lovers,

[5]

Muses, and Nymphets: Women in the Art of Nabokov," and will include papers by Marija Stankus-Saulaitis, Martin Green, D. Barton Johnson, and Jenefer P. Shute. Because of our status as Affiliated Organization in the MLA we have combined the two sections allowed us. This will provide sufficient time for the formal program and for the business meeting of the Society which will follow.

The Nabokov section at the AATSEEL meeting is scheduled for Thursday, December 29, 7:00 - 9:00 pm. The section, to be chaired by D. Barton Johnson, has as its title, "Nabokov and the Russian Emigre Literary Scene," and will include papers by Marina Naumann, Charles Nicol, Duffield White, Priscilla Meyer, with Sergei Davydov serving as discussant.

*

The most important recent event in Nabokov studies was the five months long, multi-media Festival held last spring semester at Cornell University. In the words of George Gibian, the organizer of the festival, "writers and scholars, American and European, came to the campus during the semester ’to consider various aspects of Nabokov—the writer, the translator, the critic, the teacher, and the friend.' The five months long festival included an exhibition of his butterfly collection as well as his correspondence, a film series, and a musical recital by his son Dmitri Nabokov." In this issue of the Newsletter Marilyn Kann, Slavic Studies Librarian at Cornell, describes the genesis and content of the exquisite library

[6]

exhibit. In the spring issue we will endeavor to present other reports and abstracts of as many of the talks as we can gather . The various papers and talks delivered at the Festival will be published by Cornell's Center for International Studies in a volume со-edited by George Gibian and Stephen Parker.

*

The following list of Mr. Nabokov's works published February-December 1983 was provided by Mrs. Vera Nabokov:

February 1983 - Lectures on Literature and Lectures on Russian Literature, ed. Fredson Bowers. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; two-volume boxed paperback edition.

March 1983 - Fuoco Palido (Pale Fire), tr. Bruno Oddera. Milan: Longanesi.

March 1983 - Lolita. New York: Greenwich House; distributed by Crown Publishers by arrangement with Putnam's Sons.

March 1983 - Ada Oder Das Verlangen (Ada), tr. Uwe Friesel and Marianne Therstappen. Hamburg: Rowohlt; new printing, "Jubilaumsangabe" to 75th anniversary of Rowohlt publishers.

March 1983 - Nikolai Gogol, tr. Else Hoog. Amsterdam, Holland: Uit. De Arbeiderspers; paperback in the "Open Domein" collection.

[7]

March 1983 - Selections from "Christmas" and "A Guide to Berlin" in Eric Gould, A Rhetoric, Reader, and Handbook. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

March 1983 - Littératures I. (Lectures on Literature), tr. Helene Pasquier. Paris: Librairie Artheme Fayard.

March 1983 - "Solus Rex," "'Le poeme' dit par Chichikov," and "'Parade Litteraire' par Sirine" in Annales Contemporaines LXX. Ann Arbor: Ardis; reproduction of the original issue.

March 1983 - "Fruhling in Fialta" (Spring in Fialta), tr. Dieter Zimmer. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

April 1983 - Lectures on Don Quixote, preface by Guy Davenport. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich and Bruccoli Clark.

April 1983 - Chambre Obscure (Laughter in the Dark), tr. Doucia Ergaz. Paris: Grasset, "Les Cahiers Rouges" paperback.

May 1983 - Harlekinada (Look at the Harlequins!), tr. Louis Ferron. Amsterdam: Uit. Elsevier, "Tweede Druk".

June 1983 - Lectures on Literature. Tokyo: Hidekatsu Nojima, Japanese language edition.

June 1983 - Lectures on Don Quixote, ed. Fredson Bowers. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

[8]

June 1983 - Nikolaj Gogolj, tr. Zlatko Crnkovic. Zagreb: Znanje.

July 1983 - "First Love" and Commentary, "Chekhov's 'Lady with the Little Dog'" in Ann Charters. The Story and its Writer. New York: St. Martin's Press, a Bedford book.

August 1983 - "Fruhling in Fialta" (Spring in Fialta) in Grosse Erzahler des 20. Jahrhunderts. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

September 1983 - Lectures on Literature and Lectures on Russian Literature. London: Pan Books, "Picador" paperbacks.

September 1983 - Le Don (The Gift), tr. Raymond Girard. Paris: Gallimard, collection "L'lmaginaire" paperback.

September 1983 - "Sobytie" (The Event) in Swedish translation, adapted and broadcast September 1983 by the Finnish Broadcasting Co., Ltd: OY. LEISRADIO AB. Helsinki, Finland.

*

Bruccoli Clark Publishers, in association with the Nabokov estate, is in the process of preparing a volume of VN's letter. Richard Layman, Managing Editor, has written to request that anyone who has letters written by VN or knows the location of any please contact Prof. Matthew J. Bruccoli (BC Research, 2006 Sumter St., Columbia, SC 29201).

*

[9]

In response to Simon Karlinsky's reference in the VNRN, no. 10, to "Time in The Gift," Ronald Peterson (Department of Languages and Linguistics, Occidental College, Los Angeles, CA 90041) writes:

I'm delighted that Mr. Karlinsky has read my note on time in The Gift and found my comments both "ingenious and plausible." Alas, he is much too kind in ascribing to me the honor of creating the chronology of The Gift; surely this honor belongs to Nabokov himself. I have only pointed out "Nabokov's own time span" in his novel. The reference Karlinsky mentions in the introduction to "The Circle" is at odds, but not primarily with my findings, rather with Nabokov's chronology in The Gift. Since he finds that "the rest of Peterson's timing is, oddly enough, correct," then it must be apparent that the novel begins, according to the narrator, a year after Lenin's death, a few months after Trotsky's fall from power, and seven and a half years after the Revolution (this is 1925, not 1926), and it ends one hundred years after the birth of N. Chernyshevsky, that is, 1928. It seems unlikely that the centenary of Chernyshevsky's birth would have to have been postponed to 1929 in order to fit with Nabokov's comment made in the early 1970s. After all, if Homer nods, can Nabokov lay claim to infallibility? My comments in No. 9 of the VNRN are thus not "oddly enough" correct, but an accurate reflection of the chronology in The Gift, and Nabokov's later statement about 1926-29 is, oddly, inaccurate, because if doesn't fit with his own novel.

*

[10]

D. Barton Johnson (Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages & Literatures, University of California, Santa Barbara 93106) sends along two items. In reference to the section on Nabokov in Michael Boyd's The Reflexive Novel: Fiction as Critique [for full citation see 1982 Nabokov Bibliography] Prof. Johnson notes that "Boyd provides a mildly deconstructionist reading of several Nabokov works focusing on the theme of the fictionality of the author. Primary attention is given to The Real Life of Sebastian Knight and somewhat less to Laughter in the Dark and the early short story "Terror" ("Uzhas"). Still other Nabokov works are touched upon, as are parallels to Borges."

Prof. Johnson is still interested in receiving submissions for the special Nabokov issue of Canadian-American Slavic Studies which he is editing. He is chiefly interested in things from overseas scholars who publish in languages other than English. He notes that most of the submissions so far have focused upon Nabokov as an English writer, and he would like to see more submissions by Russianists. Interested persons should contact him at the address given above.

*

Of special note in the "1982 Nabokov Bibliography" presented in this issue are the sections "Notes and Citations" and "Reference ." The former is a new section in the annual bibliography occasioned by the num-

[11]

erous notes and citations which one now finds in various publications, including the VNRN. This will continue to be a regular part of the annual bibliography. The editor asks readers to convey all such citations to him.

The three items in the "Reference" section deserve special mention. Abstracts of Soviet and East European Emigre Periodical Literature, brought to our attention by D. Barton Johnson, is a primary source for following current emigre Nabokov scholarship. It indexes and abstracts emigre periodical literature, including newspapers, and thus is an indispensable source for any Russian-reading Nabokovist. In order to help the publication survive, we encourage our readers to urge their libraries to subscribe.

Nabokov: The Critical Heritage is a collection of documents, primarily published reviews, which followed the appearance of each of Nabokov's works in English. The book has a lengthy introduction, a chronological table of VN's life and works, four items pertaining to Nabokov's works published in the 1930s (by Struve, Bitsilli, Khodasevich, Sartre), a selection of reviews (primarily British) following the chronology in which Nabokov's novels (and Eugene Onegin) appeared in English (e.g., Mary after Ada), and a select bibliography. It is a good source of materials which might otherwise be difficult to obtain and presents an interesting record of Nabokov's reception by his contemporaries.

[12]

The Nabokov entry in Dictionary of Literary Biography: Documentary Series is a handsomely produced assembly of photographs (many never before reproduced) and published documents (reviews, essays, correspondence, and tributes) pertaining to Nabokov's life and works. Like the Critical Heritage volume, it gathers materials not readily available and offers an interesting record of Nabokov's career. There is a bibliography, and the treatment, similar to the Critical Heritage volume, follows the appearance of Nabokov's works in English.

*

Renate Hof (Charlottenweg 2a, 8023 Pullach, Munich, West Germany) writes that her dissertation, "Vladimir Nabokov and the Game of Unreliable Narrator" will be published by Fink-Verlag, Munich.

*

Paul Bennett Morgan sends along the following request: "Would any subscribers interested in forming a Vladimir Nabokov Society of Great Britain please contact Paul Bennett Morgan, Department of Printed Books, National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, Dyfed SY23 3BU. It is hoped that an annual meeting and possibly an annual journal will ensue, but all will depend upon the views of the prospective membership."

*

[13]

Susan Vander Closter (Virginia Intermont College, Bristol, VA 24201) passes along Henry Miller's reaction to being thought "the real author of Lolita" from a letter to Lawrence Durrell (November 19, 1958):

"Signing off now. Just had crazy letter from hotel clerk in Monterey, saying he heard a long-distance telephone conversation to New York Times from a nut claiming he had proof that I (!) am the real author of Lolita. I haven't been able to read that book yet — opened it, didn't like the style. May be prejudiced. Usually am. As Reichel says of paintings, "A book should smile back at you when you open it, nicht war?" [Lawrence Durrell and Henry Miller: A Private Correspondence. Ed. George Wickes. New York: Faber & Faber, 1963, pp. 352-53.]

Durrell's next letter, Ms. Vander Closter notes, "makes no reference to Nabokov; consequently, whether or not Lolita smiled at him when or if he read the novel remains a mystery."

*

Dieter Zimmer (Zeitverlag Gerd Bucerius, 2000 Hamburg 1, West Germany) is currently working on the German translation of Speak, Memory, II. He also mentions that his footnotes at the end of the German translation of Bend Sinister shed light upon some of the Shakespearean allusions in that work, and should be of interest to those persons who "are trying hard to crack the code."

*

[14]

Samuel Schuman (Guilford College, Greensboro, NC 27410) has a letter in the "Forum" section of the most recent issue of PMLA (October 1983, p. 901) in which he disabuses Shari Benstoek, the author of an article entitled "At the Margin of Discourse," of what Prof. Schuman calls "a rather casual gesture of critical dismissal." In reference to Pale Fire, Benstock had written, "The radical shifts between the speakers and writers of the text and the inconsistent use of pronominal indicators (I, we, one) Illustrate the ways in which Pale Fire is at cross-purposes with itself, its author, and its intended readers." Prof. Schuman points out, gently and politely, that Benstock "confuse[s] the basic premises of an admittedly complex but extremely carefully crafted and consistent novel" in which "cross-purposes" are actually "artfully blended into a bewitching and powerful" work.

*

We continue to remain interested in ascertaining VN's place in academic curricula. In a letter from Robert Hughes (Slavic Languages & Literatures, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720) he writes that for the first time he gave a lecture course in English, "Nabokov's Russian Novels," in the Fall Quarter 1982. An additional hour per week was devoted to discussion and reading of selected stories and poetry by Nabokov in Russian. Concurrent with the course, the four films based on Nabokov's writings (King, Queen, Knave, Despair, Laughter in the Dark, Lolita) were shown at the Pacific Film Archive. He notes that it

[15]

was a gratifying' teaching experience which he hopes to repeat.

*

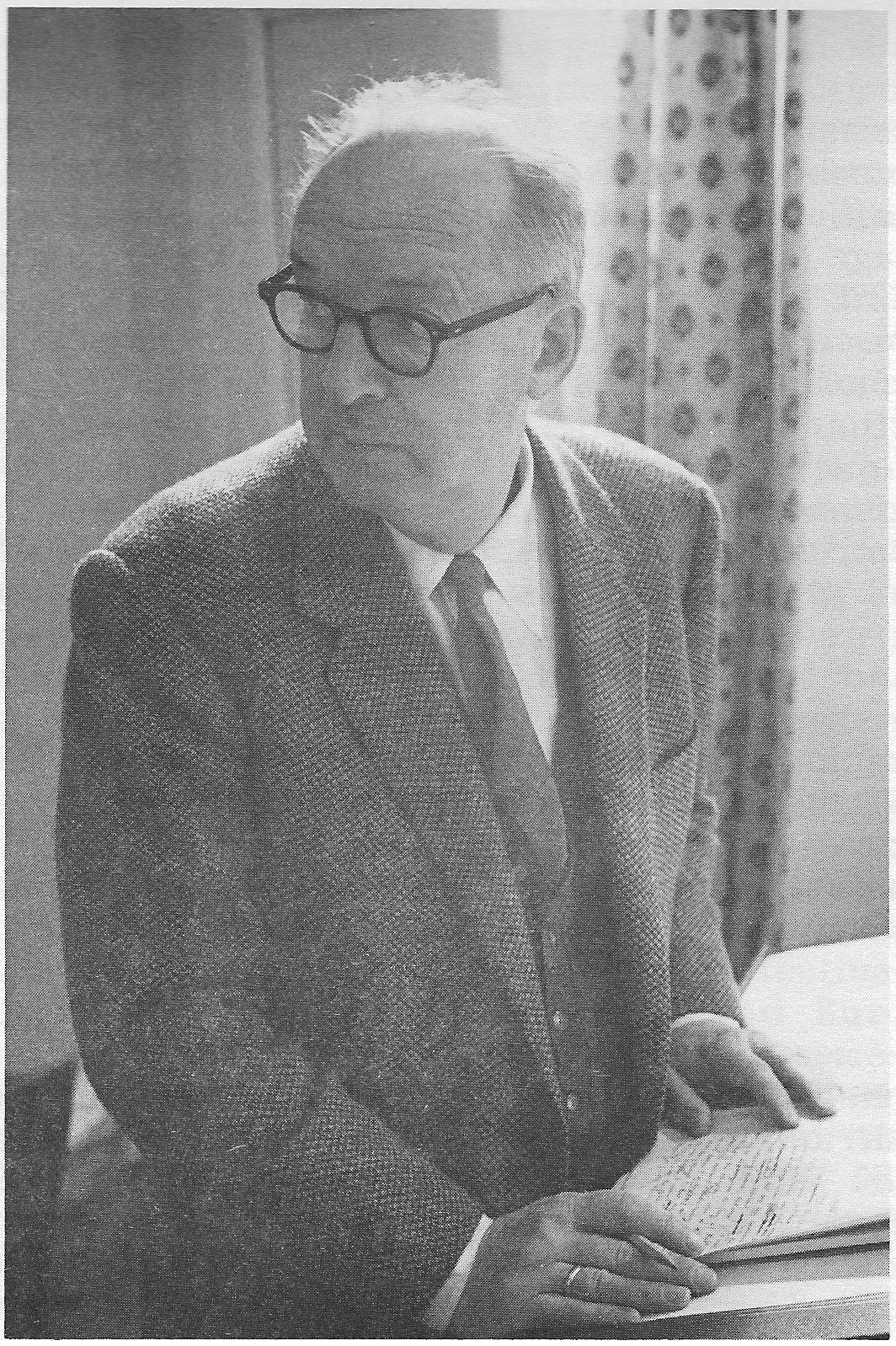

Special thanks to Ms. Paula Oliver and Mr. Chol-Kun Kwon for their assistance in putting together this issue. The photograph was provided courtesy of Mrs. Vera Nabokov.

*

[16]

Nabokov Bibliography: Aspects of the Emigré Period

by Brian Boyd

When noting in the last VNRN some pitfalls Michael Juliar should avoid in the bibliography of Nabokov's Russian works, I suggested that he take care to amass all the relevant particulars that could serve as evidence and to master bibliographic and publishing history. Now in replying to his reply I find the same division into factual particulars and bibliographic context still apt. Let us consider the second first.

As is well known, Nabokov's last six Russian novels appeared for the first time serially, in the periodical Sovremennie Zapiski. Not unreasonably, Mr. Juliar decides that these serial publications in fact constitute the first editions of the six novels. Although I have long been of the same opinion, I find Juliar's arguments misleading. He notes that novels serially published in Russian thick journals had an impact on the reading public much more significant than when subsequently published as books, and he seems to feel that this difference in impact, unappreciated by bibliographers working in the anglophone heritage, justifies altering bibliographic principle.

Juliar performs a valuable service in explaining the special role of the thick journal in Russian literary history. But it should be realized that Sovremennie Zapiski's impact--as distinct from its form—was not something it owed chiefly to tradition: its prominence in emigre culture was far greater

[17]

than that of any thick journal in prerevolutionary Russia. Normally a country has a large number of renowned periodicals competing for the educated public's patronage. The healthier the situation the more impossible it is for ordinary cultured readers to keep up with all the worthwhile periodicals and for any one periodical to be awaited with mounting expectation throughout the nation. And cultural health was certainly vigorous in early twentieth-century Russia, where every month distinguished journals like Sovremennik, Vestnik Evropy, Russkaya Mysl’, Sovremenniy Mir, Severnie Zapiski, Apollon and Zolotoe Runo, each numbering two to four hundred pages, would jostle for attention.

But in the emigration Sovremennie Zapiski emerged as the only stable periodical of major literary and socio-philosophical importance. Some potentially powerful rivals like Beseda died as life and publishing in Berlin became more difficult. Others like Volya Rossii and Chisla were able to survive for as long as six years but never looked likely to entice the leading authors from the wealthier Sovremennie Zapiski and had to close down.

The émigré market was small, the emigration's leading writers few and therefore unable to produce the vast output which could sustain Vestnik Evropy and its likes at such a high level in the 1900s. But these conditions actually increased the power of Sovremennie Zapiski by restricting it to three or four issues a year rather than the twelve of prerevolutionary journals. Because its appearances were spaced months apart

[18]

and because it was the only periodical that could be consistently relied upon for a lineup like Bunin, Sirin, Hodasevich, Aldanov and Tsvetaeva, backed up by people like Merezhkovsky, Gippius, Adamovich and Ivanov, Sovremennie Zapiski set up a rhythm of appetite and gratification that pulsed through the whole emigration.

That widespread attention was focused on each new installment of a Nabokov novel in Sovremennie Zapiski is undeniable, but "impact" can hardly function as a criterion for determining what is and what is not a first edition. Nor is the eagerly-followed serial publication of serious novels as peculiar to the Russian world as Mr. Juliar seems to think. Any bibliographer trained in Western European traditions should be familiar with great works fomenting attention when published in serial form: Madame Bovary, sending Flaubert to trial after its appearance in Revue de Paris; Great Expectations, whose publication in All the Year Round sent the magazine’s circulation higher than that of the Times; or Ulysses, which was causing too much of a stir in the Little Review for the censors to let it continue.

In an attempt to demarcate the differences between Russian and Anglo-American publishing traditions, Michael Juliar asked the rhetorical question: "Do bibliographers state that in such-and-such an issue of Esquire appeared the true first appearance of Transparent Things?" My answer was that in any case the McGraw-Hill edition antedated Esquire, though that was mere historical accident and the essential point

[19]

remains: that Nabokov submitted his manuscript first to McGraw-Hill and that only after their edition was already typeset and corrected did they then arrange with Esquire for periodical publication. Bibliographically, that is the crux: the Esquire version derives from the McGraw-Hill one which being the first setting of type made directly from the author's manuscript would be the first edition whether it had appeared a week before or after Esquire and whether or not it attracted more attention than the magazine version.

Ignoring my emphasis, Juliar replies that if Transparent Things had first appeared in Esquire, "it would still not have had the impact on the literary world that the serial publication of Zashchita Luzhina in Sovremennyia zapiski did in 1929-1930. That is the point." (VNRN 10, p. 38) It is a point, but it does not constitute a cultural difference that requires changing the logic of bibliography. In terms of "impact"— sales, readership, a flood of fan mail--the much-loved New Yorker chapters of Conclusive Evidence fared far better than the badly advertised and badly timed first edition (Harper, 1951), which according to Samuel Schuman (Vladimir Nabokov: A Reference Guide, Boston: G. K. Hall, 1979, p. 19) received only one review — before the measly sales of its small printing run dried up altogether.

Dickens in publishing serially would send chapters off before he knew exactly how his novel would continue, revising for consistency only when he was preparing the

[20]

novel for book publication after it had finished its serial run: a good argument against regarding his serial works as first editions. Like Dickens, Nabokov was seeking "impact"— and money — in the interim when he sent chapters of Conclusive Evidence and Pnin to the New Yorker. Although he submitted all chapters of both books, the New Yorker rejected some. But even had every chapter been published the periodical versions would be in the position of Dickens's serial novels, since Nabokov still had the rest of Conclusive Evidence and Pnin to write when their earliest installments appeared in the New Yorker. For Sovremennie Zapiski on the other hand Nabokov had always finished the entire novel (or in the case of Par at least the entire first draft) before submitting the first part of the manuscript. What makes the Sovremennie Zapiski versions first editions is not their impact — which after all varied from reader to reader — but the fact that they were here set in print for the first time, in unabridged form,(1) directly from Nabokov's manuscript and after he had completed the novels.

Michael Juliar's insistence on the Sovremennie Zapiski texts arises in part from his respect for the importance of chronology in a writer's artistic evolution. The Sovremennie Zapiski order of Nabokov's novels

______________________________

(1) The New Yorker version of The Defense, which Juliar implies could be a first edition if American serial publication had the supposedly unique impact of serial publication à la russe, was in fact an abridgement.

[21]

conveys much more accurately the order of composition and first appearance than does the sequence of the book versions. Juliar's fine sensitivity to sequence and date combines with his passion for precision when he examines newspapers for evidence of the exact dates of publication of Nabokov's early books.

After working through a microfilm of Rul' Mr. Juliar offered an avowedly tentative dating of Nabokov's émigré books (VNRN 9, pp. 14-24). Unfortunately it is not tentative enough. Let us focus on the first three of the books Juliar lists.

The earliest of the three, according to Juliar, was Gorniy put', which "was certainly published and on sale in November 1922." His evidence for this is that on 19 November 1922 Grani placed in Rul' "a display ad for books on sale" that included Gorniy put'. However the advertisement is headed not "books on sale" but "new basic prices," and it seems clear that it included books not yet on sale. Five other books in this advertisement, for instance, appear in a later Grani ad (Rul’, 5 December 1922), as "Poslednie novinki" ("latest novelties"); significantly, Gorniy put' does not figure here. Customarily emigre publishers would announce books not only when they came on sale (and often beforehand) but also in the weeks immediately following publication. Bookstores would also list new stock. But there is none of this backup advertising in Rul' for Gorniy put' — and this in late November and December, when booksellers were trying to advertise everything they could for Christmas.

[22]

The earliest review of Gorniy put'—in fact a review also of Grozd' — seems to be the one in Rul' on 28 January 1923. On the same day, Dni printed a Grani ad announcing among the "New Books: Now on Sale" Gorniy put', which had not been listed in Gram's last Dni advertisement six weeks before (another Christmas opportunity lost, if the book had really been available). In Dni on 18 February 1923, Gorniy put' appears among the "books received by the editors between 9 and 16 February." Since a delay of three weeks or so between publication and inclusion in such a list of books for review was common (see Grozd' below) it seems likely that Gorniy put' was published around 20 January 1923, if we allow a week for the review.

(It might seem odd that Rul’ should publish a review before another daily from the same city even records the arrival of its review copy. But in fact it was not uncommon for a newspaper's review to precede by a week or two the announced arrival of its own review copy. Often though not always the dated receipt of review copies can serve only as a tardy terminus ad quern.)

The next book in Juliar's dating is Nikolka Persik. He writes that its "first mention" occurred in Rul' on 26 November 1922. In fact a week before in the very issue of Rul' Juliar used to date Gorniy put' there appears a major review by Yuri Ofrosimov of Nikolka Persik. The first advertisement in Dni appears on 24 November 1922, and in both Dni and Rul' backup publishers' ads and bookstore ads begin to trickle at once.

[23]

Juliar records that Grozd', the third book on his list, is both advertised and reviewed in Rul' on 28 January 1923, the only issue for January-March 1923 available to him. But it had been advertised repeatedly in Rul' during December 1922. On the 10th it was "coming out in the very near future," on the 17th and 19th "coming on sale 18th December," and in the issues of the 24th and 31st it appears as "now on sale" in two different advertisements each time. The first mention of Grozd' in Dni seems to be on 14 January 1923, when the book is both reviewed and listed among books received "between 29 December 1922 and 11 January 1923." All the evidence here suggests that the book did appear as announced on 18 December 1922.

In the second installment of his "Notes from a Descriptive Bibliography" Juliar tabulates both Field's and his own dates and ordering of Nabokov's first three emigre books (VNRN 9, pp. 14 and 21). A comparison of Field's, Juliar's and my own tentative dates indicates the difficulty of shelving the books chronologically:

Field Juliar Boyd

1922 NP xi.22 GP by 19.xi.22 NP

1923 GP xi.22 NP 18.xii.22 G

1923 G iv. (sic)23 G c.20.i.23 GP

Michael Juliar seems to have overlooked a considerable amount of evidence even in the Rul' microfilm on which he was working.

[24]

That microfilm is incomplete, although the missing issues can be located in Europe (especially Helsinki, Oslo, Prague, East Berlin, Amsterdam and Paris). But Rul' is only one part of the newspaper evidence. For 1922-1923 Dni (Berlin), Poslednie Novosti (Paris) and Segodnya (Riga) need also to be consulted. Newspaper evidence for dating emigre publications can be partial or misleading, and between 1921 and 1924, in the heyday of Berlin publishing, the sheer plethora of advertisements makes it easy for information to be skipped past. It is imperative to consult more than one newspaper source, and to sift the columns of print with the utmost care. Bibliographic work can be nauseatingly tedious but it has to be painstaking and as slow as one can stand if it is to produce the precision Juliar is right to aim for.

University of Auckland

Auckland, New Zealand

Michael Juliar replies: "I thank Mr. Boyd for his comments and gratefully accept his insights and corrections. He is doing a service in helping make my bibliography as accurate as possible. I hope to keep in contact with him. "

[25]

Vladimir Nabokov: An exhibition of Correspondence, Photographs, First Editions, Butterflies …

by Marilyn В. Kann

An exhibition of materials by and about Vladimir Nabokov was held in Olin Library, Cornell's central research library, from late January through the end of March, 1982, as

[26]

part of the Nabokov Festival. When first considering the possibility of arranging the exhibit, I was concerned that Olin did not have a varied enough collection of materials to make for an interesting display. What Olin did have, in its Rare Book Department, was a fine and nearly complete collection of editions of Nabokov's published work, including some very rare and early publications. One of its prizes is a copy of the Russian translation of Alice in Wonderland (Berlin, Gamaiun, 1923). The library, however, sadly lacked any archival materials or photographs, with the exception of the two official mug shots contained in Nabokov's faculty file in our Manuscripts and University Archives Department. An exhibit displaying only title pages of published materials would perhaps provide a sound enough bibliographic record of his work, but it did not seem worthy of a writer whose life was so rich and whose personality so outspoken, charismatic, and contentious. In addition, I wanted the local community to see more personal materials relating directly to Nabokov's years at Cornell. It was clear that the first step in mounting the exhibit would be to gather materials from outside the library, from within the Cornell community (both past and present), and, where necessary, beyond it. The detective work and personal contacts at this early stage of the project were both productive and enjoyable.

The first person to whom I turned was Alison Mason Kingsbury (Mrs. Morris Bishop), widow of Professor Morris Bishop, Nabokov's one true and lasting friend at Cornell. She responded generously, lending

[27]

for the exhibit her invaluable collection of letters from Vladimir and Vera Nabokov to her and her husband. The correspondence, both typed and handwritten, spans the years 1956 to 1972 and ranges from serious literary commentary (such as Nabokov's assessment of Robbe-Grillet as the greatest living French writer) to progress reports on his own writings, to a precisely off-color exchange of limericks between Nabokov and Bishop (Morris Bishop was a prolific producer of limericks.) In one letter Nabokov ranks Lolita his best book to date and urges Bishop to finish reading it. Morris Bishop never did approve of the book, considering it his friend's one mistake in literary judgement. The Bishop letters were interspersed throughout the exhibit according to their subject matter.

Mrs. Bishop also lent the library her large collection of Nabokov first editions, personally inscribed by the author. Many bear the butterfly insignia. In one of the books, Nabokov spells the name of the recipient with a pictogram of chessmen [bishops] and signs it "From the author of Sebastian..." [followed by another chess-piece, a knight].

With Mrs. Bishop's help, I tracked down a reference in one of the letters to a "Papilio waterclosetensis". The animal was one of Nabokov's butterflies, drawn on the butterfly-design wallpaper of the WC in the Bishops' former residence in Ithaca, in an attempt to correct the biological inaccuracies in the wallpaper's print. Cornell Senior Vice President William G. Herbster, present owner

[28]

of the WC (and house), informed me that the wallpaper has since been painted over. As was noted in the exhibit, there are no plans for an excavation.

Nabokov's former Cornell students Stephen Jan Parker and Alfred Appel, Jr. also made significant contributions. Stephen Parker lent his handwritten and typed class notes from Literature 311-312, Masters of European Literature, complete with Nabokov's literary diagrams copied down from the blackboard. It was interesting to compare them with Nabokov's own drafts and diagrams of the same lectures in the published Lectures on Literature (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980) next to which they were displayed.

The fifty-five photographs lent by Alfred Appel, Jr. provided a striking visual record of Nabokov's adult life, from the emigre years in Europe to his final years in Montreux. This amount of portraiture might well have been too much if the subject were less photogenic, physically impressive, and expressive than Nabokov was, but Appel's collection added immeasurably to the exhibit without causing an overdose.

Other Cornell faculty members, active and retired, also provided personally inscribed copies of Nabokov books and shared with me personal recollections of their former colleague.

Finally, Mrs. Vera Nabokov kindly sent from Montreux several photographs of Nabokov, including a beautiful portrait by Hals-

[29]

man; copies of a handwritten draft and notes to Nabokov's poem "The Poplar"; and a copy of a handwritten draft of Nabokov's final examination for Literature 311-312, which includes detailed instructions on bathroom visitation rights during the examination. (This last may have been one of the highlights in the exhibit for Cornell undergraduates.) I deliberated, but only briefly, before displaying the draft and notes for the poem, remembering Nabokov's answer to the question, "Can you tell us something more about the actual creative process involved in the germination of a book..." "Certainly not. No fetus should undergo an exploratory operation" (Interview in Playboy, January 1964).

The thematic arrangement of the exhibit was partially dictated by the curious configuration of Olin Library's twenty-seven display cases, which are broken up into several clusters in various parts of the library. Their physical arrangement is thus not conducive to one continuous theme. I decided, therefore, to divide the exhibit into meaningful motifs that could be experienced both linearly and by topic.

The thirteen cases in the Rare Book Room contained that department's collection of Nabokov editions, as well as other biographical material and criticism drawn from the Olin general collection. Nabokov's life and works were divided into three major periods, based on the divisions of J. E. Rivers and Charles Nicol in Rivers, J.E. and Charles Nicol, eds., Nabokov's Fifth Arc: Nabokov and Others on His Life's Work,

[30]

Austin, University of Texas Press, 1982: Russia and Europe (1899-1938); America (1940-1958); Return to Europe (1960-1977). The first few cases included photographs of Nabokov's parents and his house in St. Petersburg; his father's publications; his poem "Lunnaia greza", published in Viestnik Evropy in 1916; the "Universitetskaia poema" (accompanied by a photograph of Nabokov rowing at Cambridge); examples of his poetry published in the visually stunning journal Zhar ptitsa; and the Ania v strane chudes (Berlin, Gamaiun, 1923). The cases continued with a chronologically arranged record of Nabokov's life and works. The first mention of Nabokov (as Vladimir Sirin), which appeared in The American Mercury, ed. H. L. Mencken, July 1933, was traced down and displayed here. A Phaedra Publishers publicity sheet accompanying an advance copy of the first English edition of The Eye (Phaedra, 1965) optimistically proclaims the book a "wild spy story that could easily be the successor to The Spy That Came in from the Cold. "Introducing the section on "America" was Nabokov's sad farewell to the Russian language, the poem "Softest of Tongues". Letters to Morris Bishop referring to specific Nabokov works in progress accompanied the books. Original appearances of stories and poems were displayed here in copies of The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, Playboy, and other journals. In a November 1943 publication of a Nabokov story by The Atlantic Monthly, an editor notes at the bottom of the page, "...In recent years [Nabokov] has mastered the difficulty of writing in English." The two passages from Pnin which take place in

[31]

the Waindell College Library were marked and greatly amused viewers who had not read the novel. The Rare Book Room display concluded with John Updike's unsigned obituary on Nabokov in The New Yorker, July 18, 1977. The captions, here as throughout the exhibit, were, wherever possible, put together out of Nabokov's own words.

Excluded from the Rare Book Room was Lolita. Due to its long and complicated publishing saga and its peculiar relation to Cornell as the culmination of Nabokov's "American" years, it was placed in the "Cornell" section of the exhibit. The seven cases in the front lobby of the library held materials relating specifically to Nabokov's Cornell years and to Lolita. The Cornell cases contained such items as Morris Bishop's invitation to Nabokov to become a Cornell faculty member; the course materials mentioned above; quotations and interviews by Nabokov on the subject of Cornell; the now famous mistaken classroom incident, narrated by Alfred Appel, Jr. ("Nabokov: A Portrait," Atlantic, September 1971); a Cornell college catalog describing his courses; and material relating to the friendship between Bishop and Nabokov. A page of the May 15, 1948 New Yorker was displayed on which a Nabokov story and a Bishop poem appear, coincidentally, before Nabokov's move to Cornell.

Among the materials in the Lolita section were its first editions; the pamphlet published by Olympia Press protesting its ban in France (L’Affaire Lolita: Défense de

[32]

l'Ecrivain, Olympia, 1957); Putnam's announcement of the first American edition; the Paris L'Express newspaper article, December 28, 1956 reporting the banning of Lolita by the Minister of the Interior and its assessment by Graham Greene as one of the most important works of contemporary literature in the English language ("Pun des plus importants de la littérature contemporaine"); and Nabokov's poem "What is the evil deed I have committed" ("Kаkое sdelal ia durnoe delo...") (1959, San Remo). Here also were examples of local reaction to Lolita from the Cornell Daily Sun, the student newspaper (including a review by Richard Farina, then an undergraduate at Cornell) and cartoons about the book from copies of the New York Times Book Review in 1958 and 1959. Two definitions of "nymphet", the first from the Oxford English Dictionary, 1933, the second from the Oxford English Dictionary, 1976 Supplement, were placed side by side, pointing out Nabokov's impact on English-speaking culture. Such tidbits and contrasts, I might add, were great fun to think up and document.

Also included were Nabokov's own feelings about Lolita, expressed in interviews (The Listener, Nov. 22, 1962 and Playboy, January 1964), letters to Bishop, and in the "Postscript to the Russian Edition of Lolita," 1965 (translated into English by Earl D. Sampson in Nabokov's Fifth Arc, eds. J. E. Rivers and Charles Nicol, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1982). On the many translations of Lolita Nabokov concludes in the "Postscript", "… I can answer as to accuracy and completeness only for the

[33]

French one, which I checked myself prior to publication. I can imagine what the Egyptians and Chinese did to the poor thing."

A small section, comprising only two cases in the corridor of the library leading to the stacks, was devoted to the Nabokov-Wilson "friendship". Here was the well-known epistolary war between the two, in its original appearances in The New York Review of Books, The New York Times Book Review, and Encounter, as well as Wilson's rather nasty account of a visit with the Nabokovs in his Upstate: Records and Recollections of Northern New York (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1971). However, I also tried, I think successfully, to select for display letters from Simon Karlinsky's The Nabokov-Wilson Letters that represent the many years of truly warm personal and intellectual friendship between the two writers (The Nabokov-Wilson Letters: Correspondence Between Vladimir Nabokov and Edmund Wilson, 1940-1971, ed. Simon Karlinsky. Harper & Row, 1979). Here also was the translation of Pushkin's "Mozart and Salieri," first published in the New Republic, April 1941, on which the two friends collaborated.

Last, there was Nabokov as lepidopterist, or, more broadly, the theme of Nabokov and butterflies. It was treated in the six cases on the lower level of the library. I combined here some references to butterflies in Nabokov's literature (from Speak, Memory and the poems "Lines Written in Oregon" and "On Discovering a Butterfly") with Nabokov's own thoughts, letters, and articles on lepidopterology.

[34]

The highlight of this section was the Nabokov butterflies themselves. During his years at Cornell, Nabokov continued to collect lepidoptera, in New York State and on summer trips to the American West. He donated some of these to the Insect Collections of Cornell's Entomology Department, with his handwritten labels, where they can be viewed in drawers in a room full of less literary insects.

John Franclemont, Professor Emeritus of Entomology, was on the faculty during Nabokov's Cornell years and kindly assisted me in exhibiting some of the lovely specimens . He shared with me many anecdotes about his field trips with Nabokov in the Ithaca area, in the process educating me on some of the literary references to lepidoptera. The "esmerelda" in "Lines Written in Oregon," for instance, is a gold-colored day-flying moth found in Eurasia and western North America, an apparition, as it were, from Nabokov's Russian past.

The "blue of extraordinary intensity," which Nabokov describes in the beautiful opening passage of Chapter Six of Speak, Memory and which he later rediscovered in western Colorado, was also on display. This Lycaeides argyrognomon (sub species) sublivens Nabokov was "discovered" and described by Nabokov and is indeed a "Nabokov" butterfly.

A large copy of Philippe Halsman's striking photograph of Nabokov with net stalking a butterfly was in this section, along with many others of him mounting

[35]

butterflies, working in the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, and walking net in hand in the Swiss countryside accompanied by Alfred Appel, Jr.

During the years Nabokov worked as a research fellow in lepidopterology at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, from 1942 to 1948, he corresponded with W. T. M. Forbes, then Professor of Entomology at Cornell. Among Forbes’s as yet uncataloged letters in the collection of Olin Library's Manuscripts and University Archives Department, I found four from Nabokov. Three are handwritten and all are on the subject of lepidopterology. These were displayed, though I do not believe many visitors were interested in their contents. On the other hand, for some visitors, were was not enough scientific material. Due to an error in the announcement of the exhibit in one of the local newspapers—which advertised the entire exhibit as "Nabokov's butterfly collection " — one Saturday brought in a group of out-of-town entomologists. Expecting to find the entire library filled with lepidoptera, they were rather disgruntled.

One welcome result of the exhibit was a generous donation by the Cornell Library Associates for the purchase of Nabokov materials. With it we filled some of our remaining gaps of first editions, which included Nabokov's translation into Russian of Romain Rolland's Colas Breugnon (Berlin, Slovo, 1922).

The exhibit was, I believe, "well received", judging from the verbal and written

[36]

comments I read and heard. There were two reactions that I heard repeatedly from viewers who had not been closely familiar with Nabokov's work: one was astonishment at how much he had written and published in Europe before he became known to them; the second was that he had such an excruciating wit. I cannot imagine a personality more "exhibitable"— as a writer, teacher, correspondent, and source for memorable quotations . The opportunity to collect and display these Nabokov materials I count among my most rewarding projects as Slavic Studies Librarian at Cornell.

[37]

ABSTRACT

"Who Wrote This Book?"

by Charles Nicol

(Abstract of a paper presented at the MLA Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, December 1982)

"Who wrote this book?" is a question asked and a game played in many of Nabokov's works. The game is played whenever the "real" author is revealed only at the end of the novel or story; it results in the reader being forced to view the work from a new perspective and ideally, re-reading it. Three main types are identified: 1) the author turns out to be Nabokov, who has become a character—as in Pnin, where Nabokov personally enters the narrative in the last chapter; 2) the author turns out to be someone else instead of Nabokov, even though Nabokov's representative is present—as in The Gift, where the author turns out in the last chapter to be Godunov-Cherdyntsev rather than Vladimirov (or Nabokov); 3) the author turns out to be dead, termed here a "ghost-writer"— as in Transparent Things, where the author turns out, in the very last sentence, to be Mr. R.

Sometimes this game can be quite elaborate. In "Spring in Fialta," the author at first appears to be the Russian émigré narrator, then appears to be the "lean and arrogant" writer Ferdinand who appears "in decorous disguise," but eventually turns out

[38]

to be Nabokov himself, mistakenly identified by the narrator as an Englishman. The Real Life of Sebastian Knight turns out to be written by both V. and the ghost-writer Sebastian.

With these introductory examples, the paper concentrates on Glory, an early novel that ends in a decided quiz. Summary discussions establish three points: 1) Martin Edelweiss died in his attempt to cross the Russian frontier; 2) ghosts are important throughout the novel; and 3) Martin continually attempted to become a character in the works of various writers. The paper then argues that the game of "who wrote this book?" should be answered: Darwin wrote it with the help of Martin as ghost-writer. Initial contact between Darwin and Martin's "ghost" occurs at the end of the final chapter.

A brief final section argues that a paragraph in Nabokov's introduction joins this game with a second game (a chess problem), and then shows how these two games might coincide in Martin's triumphal sacrifice.

[39]

ABSTRACT

"Nabokov's Poetry of Chess: the Problems in Speak, Memory"

by Janet Gezari

(Abstract of a paper presented at the MLA Annual Meeting, Los Angeles, December 1982)

Nabokov's chess problems contribute to our understanding of his novels less because pieces and moves in them resemble characters or events in the novels than because the chess problem is an especially good model for Nabokovian narrative structures and strategies. A brief account of the difference between chess problems and chess games and an analysis of two important problems demonstrates the relationship between the temporal and spatial properties of chess problems and those of narrative. Nabokov's description of the way a "sophisticated" solver would solve one of these problems as both a narrative journey through "strange landscapes" and a Hegelian triad describes the structure of Speak, Memory as a whole and some of its characteristic narrative strategies.

[40]

ABSTRACT

"Text and Pre-Text in Nabokov's Defense"

by D. Barton Johnson

(Abstract of a paper prepared for the 1982 MLA Nabokov Special Session and to appear in Modern Fiction Studies)

The article proposes that Nabokov's prefatory comments about how chess works in The Defense are intentionally misleading. Such indirection is a common attribute of the chess problems that Nabokov composed and published over the years. I counter Nabokov’s possibly deceptive comments with the argument that the pattern of repetition that structures the two parallel halves of the novel is based upon an event in chess history wherein a famed player went mad presumably in consequence of twice falling victim to the temptation of a spectacular double rook sacrifice. The hero of Nabokov's novel makes the same mistake (on a biographical level) with the same result. The article offers a general consideration of the use Nabokov makes of games (especially chess) in his art.

(This article will also appear as a chapter in my forthcoming book Worlds in Regression: Some Novels of Vladimir Nabokov (Ardis Publishers, 1984).

[41]

ANNOTATIONS & QUERIES

by Charles Nicol

(Note: Material for this section for the Spring 1984 VNRN should be sent to Stephen Jan Parker. For the Fall, it should be sent to Charles Nicol, English Department, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, IN 47809. Deadlines for submission are March 1 for the Spring issue and September 1 for the Fall. Unless specifically stated otherwise, references to Nabokov’s works will be to the most recent hardcover U. S. editions. )

Two Notes on Lolita

"Between the age limits of nine and fourteen," says Humbert Humbert, "there occur maidens who, to certain bewitched travelers, twice or many times older than they, reveal their true nature . . . " (p. 18). "Bewitched travelers" make one think of Nikolay Leskov's (1831-1895) long story Ocharovannyi strannik (1873). In Nabokov’s own translation of Lolita into Russian, "to bewitched travelers" is rendered as "dlya ocharovannykh strannikov" (p. 8). So Nikolay Semyonovich Leskov probably should be added to the long list of authors Lolita alludes to, compiled by Carl R. Proffer in his Keys to Lolita.

Humbert Humbert's first marriage was to Valeria Zborovski, "the daughter of a Polish doctor" (p. 27). In fact, Humbert's wife must have been called — at least by Poles — "Waleria Zborowska," Zborowska being

[42]

the feminine counterpart of Zborowski; the Christian name Waleria (pronounced Valerya) is used in Poland, but the diminutive Valechka (p. 31) is a Russian one (in Polish it would be Walercia).

Zborowski is a Polish name of some significance. In the 16th century the magnate Samuel Zborowski, banished after killing a castellan of Przemysl, returned to plot against the king; in 1584 he was captured and beheaded. An unfinished drama entitled Samuel Zborowski by the great Polish romantic poet Juliusz Slowacki (1809-1849) was published posthumously, and while I doubt that Nabokov had read Slowacki's work, it was translated into Russian by Konstantin Dmitrievich Balmont and published in 1909 and 1911 under the title Gelion-Eolion. However, Nabokov might well have heard of Leopold Zborowski (1889-1932), the Parisian art-dealer of Polish origin, protector of Modigliani and Soutine. There are famous 1918 portraits of Zborowski and of his wife painted by Modigliani. [When first seen by Humbert, Valeria is behind an easel, painting "cubistic trash" (p. 27). Later, they eat most of their meals in a restaurant with a foreign clientele, on the rue Bonaparte; next door is an "art dealer" with, apparently, a Currier & Ives print in his window (pp. 28-29). I would guess that Nabokov gave Valeria the art dealer's name in order to help identify the restaurant at which he (or Humbert) ate at that time in Paris. Could our correspondent--or anyone else--verify that Zborowski's gallery was on the rue Bonaparte, and perhaps identify the restaurant? — CN]

— Leszek Engelking, Warsaw, Poland

[43]

Chevalier/Chevalier

"The American hospital in Valvey, next to the Russian church built by Vladimir Chevalier, his granduncle, proved to be good enough for diagnosing advanced tuberculosis of the left lung" (Ada, III, 8, p. 528). The assumption that "Valvey" should be read as "Vevey" (a city west of Montreux on the Lake Geneva coast) proves right in the case of the Russian church. Founded by Count and Countess Schouvalov in memory of their daughter Varvara, Countess Orlov, and the Countess's baby-daughter— some will say her sister but recent research has disproved it—the church is dedicated to St. Barbara. "An architectural jewel, a flower of Russia in Vaudois land," it was inaugurated in October 1878. It is still used periodically for services in Slavonic according to Greek orthodox rite. That Count Schouvalov should be given the droll homophonous name of Vladimir Chevalier and the casual title of granduncle to Ada's husband seems a very nice point of "semantics — or semination," as Demon might have it.

— Jean-Louis Chevalier, University of Caen

Nabokov and Zhukovsky

One of the most important episodes in Invitation to a Beheading occurs in Chapter Eight, when Cincinnatus records his reflections on his imprisonment and reveals that he has been harboring, a vision of a "more genuine reality" existing beyond the "vaunted waking life" in which he is currently

[44]

confined (Invitation to a Beheading, New York: Capricorn Books, 1959, p. 92). In a lyrical passage beginning "There, tam, là-bas . . ." (p. 94) he sets down his vision of this more beautiful reality. Commenting on this passage, several critics have pointed out that Cincinnatus' words echo a line from Baudelaire's poem "L'Invitation au Voyage:" "Là, tout n'est qu'ordre et beauté, / Luxe, calme et volupté" (see Robert Alter, "Invitation to a Beheading: Nabokov and the Art of Politics," TriQuarterly, 17 [Winter 1970], 45 and Dale E. Peterson, "Nabokov's Invitation: Literature as Execution," PMLA, 96, No. 5 [October 1981], 828). Taking a different approach, D. Barton Johnson has connected the sound play in the tut/tam (here/there) opposition with sound symbolism in Andrey Bely's work (see Johnson's article, "Bely and Nabokov: A Comparative Overview," Russian Literature, 9 [1981], 392-393).

A third writer whose work may have been an inspiration to Nabokov here is the poet Vasily Zhukovsky (1783-1852), an early forerunner of Russian Romanticism who wrote eloquently of the opposition between a disheartening or confining realm "here" and a free, uplifting realm that exists somewhere "there." In a series of poems written in the 1810s Zhukovsky repeatedly expressed dreams of more fulfilling spaces than the ones currently inhabited. A typical poem with this message is his "Song" ("Pesnia") of 1815. Looking forward from the depths of winter to the joys of spring, the poet speaks of blooming roses:

[45]

Somewhere, they promise us,

Exists a better land.

There [tam] spring lives

Eternally young;

There [tam], in a valley of paradise

A different life

Blossoms for us like a rose.

Similarly, the poem "Spring Feeling" ("Vesennee chuvstvo," 1816) presents the poet's emotions of renewed longing and hope in springtime. The poet speaks of an unspecified realm "there" (tam) as a potential place of enchantment and asks, "Oh, who will tell me, will an enchanted There ever be found?" ("Akh, naidetsia l’ kto mne shazhet, / Ocharovannoe Tam?"). In another "song," "The Song of a Poor Man" ("Pesnia bednia-ka," 1816), Zhukovsky concludes with a poor man's vision of a feast in heaven: "There [tam] I too will celebrate; / There [tam] exists a place even for me."

Finally, in an untitled poem written in 1816 ("Tam nebesa i vody iasny!") Zhukovsky puts forth a vision of a radiant realm much like Cincinnatus' vision of the Tamara Gardens where he once wandered with his beloved. I quote it in its entirety because its resonance extends beyond Invitation to a Beheading.

There the sky and the waters are clear!

There the songs of the little birds are mellifluous!

Oh homeland! All your days are beautiful!

[46]

No matter where I have been, I am always with you

In my soul.

Do you recall how, near the mountain,

A ray made silver by the dew

Would show white during the eventide

And a hush would descend on the forest

From the sky?

Do you recall our peaceful pond,

And the shadow from the willows during the sultry noon hour,

And the dissonant honking of a flock over the water.

And in the bosom of the waters, as if through glass.

The village?There in the dawn a little bird would sing;

The horizon would light up and grow bright;

Thither, thither my soul would fly:

To my heart and eyes it seemed —

Everything was there!..

Not only does the evocation of remembered and imagined beauty "there" recall the passages id which Cincinnatus envisions the Tamara Gardens (see pp. 19, 27-28) or his special dream world (p. 94), it contains a pattern which would be repeated several times in Ada too. Just as Zhukovsky's lyric persona asks "Do you recall … " ("Ту pomnish' li ..."), so too does Van address Ada in a poem with the question, "My sister, do you still recall … : ( "Sestra

[47]

moya, ti pomnish' … Ada, New York: McGraw-НШ, 1969, p. 138). The sentimental and romantic aura evoked by Van in his memoir corresponds well with the mood suggested in Zhukovsky's poetry.

Although one finds little reference to Zhukovsky or his work in Nabokov's interviews or autobiographical writings, Nabokov does mention Zhukovsky many times in his commentary to Pushkin's Eugene Onegin, revealing both an extensive knowledge of Zhukovsky's work and an appreciation for the poet's "strong and delicate instrument" (see Nabokov's commentary to Eugene Onegin, Volume 3, p. 145).. One cannot be certain that Zhukovsky's poetry played a role in the formulation of Cincinnatus' vision of an ideal realm existing "there," but the parallels are noteworthy. Cincinnatus would surely have found Zhukovsky's lyric expressions quite compatible with his own Romantic yearnings.

— Julian W. Connolly, University of Virginia

Abraham Milton

In an essay on Ada, while noting that Van remembers Warren Gamaliel Harding as being president "from the time of Lincoln," I pointed out further discrepancies in Van's knowledge of the earlier president:

He cannot remember Lincoln's name, once referring to him as "Abraham

Milton," a second time as "Milton Abraham ," and when finally naming him

[48]

correctly gives Lincoln an extremely attractive second wife (I wish I knew

where that "Milton" came from). Van correctly recalls that Lincoln had something

to do with the purchase of Alaska from Russia, but then confuses the two

… (Nabokov's Fifth Arc, pp. 238-39).

Now Paul Chironna (graduate student. University of Chicago) has answered my wish: "May I suggest that the Milton in 'Abraham Milton' is none other than the English poet, the connection being his glancing involvement in another Civil War of sorts?" Further connections seem to verify Mr. Chiron-na's conjecture. Under Cromwell Milton was Secretary of Foreign Tongues to the Council of State, a position equivalent to Seward's position as Secretary of State when Alaska was purchased. Milton's first wife was named Mary, as was Lincoln's wife, and Milton's remarriage seems to explain the second wife Van assigns to Lincoln. The only direct connection I have found so far between the two names is almost too slight to mention: a life of Milton by his nephew Edward Phillips mentions that "he left his great house in Barbican, and betook himself to a smaller in High Holburn, among those that open backward into Lincoln's Inn Fields." Why Van was interested in Milton is easier to state: not just because Ardis is a Paradise Lost but also because Andrew Marvell--a central poet in Ada — was at one time Milton's assistant. Incidentally, Marvell and Milton were both, like Nabokov himself, Cambridge graduates.

—CN